Abramovič’s space of being

The Marina Abramović retrospective is on view at Kaunas Picture Gallery through July 31.

On the occasion of Kaunas being the European Capital of Culture for 2022, on March 30 the Marina Abramović exhibition Memory of Being opened at the Kaunas Picture Gallery, a branch of the M. K. Čiurlionis National Art Museum. Representing fifty years of Abramović’s performances – from the 1960s to the present – the show is being organised by the Meno Parkas gallery, with curators Wacław Kuczma, Dorota Kuczma and Arvydas Žalpys, and exhibitions design architects Jeroen de Vries and Marina Dokmanovič. At the press conference for the opening, the number of photographers and journalists awaiting Abramović’s arrival was much like one would expect for the reception of a rock star. “When I started my performance art, my public was five friends. Ten people were, like, a lot. 30 people? Wow, a big audience! Now we have hundreds and thousands. It’s a huge jump from 50 years ago to now. But it’s very interesting.”

This exhibition is a unique event in its form and scope, allowing us to glimpse Abramović’s life and the essence and power of her art. When asked how it feels to see her entire creative life in one place, she said: “You are dealing with somebody who doesn’t have one gram of nostalgia. I don’t care. I don’t feel anything because I live in the now and the future. If I look at the past all the time, I will be in the past, and I don’t want to be in the past. You know, my generation is so nostalgic and thinks about great old things. I don’t look at things this way. Things happen. I’ve given all my energy to those works. This work is not for me anymore. This work is for the world and I am now divorced from it. I’m always thinking about what I’m doing now and what I’m going to do next.”

Supported by image and sound,the minimalist framework of the exhibition creates a meditative space where narrative and message have the opportunity to emerge in all their layers. Only two artefacts have been selected to be shown – replicas of the table and chair used by Abramović in her now legendary performance The Artist Is Present (2010) at MoMA in New York city. “When you’re a younger artist, you need more things. When you get older, you need less because when you’re young, you’re so insecure. You know, in my latest work, I don’t need anything. I need you and me. Maybe a chair, maybe not. Because you understand how energy flows. It’s all about energy and energy is invisible, but you can feel it. That’s the thing.”

From the very first part of the exhibition, the viewer is directly confronted with the essence of Marina Abramović. The original version of the performance Lips of Thomas, which took place at the Krinzinger Gallery in Innsbruck in October 1975, was not documented. The only evidence of it are the photographs that slowly replace each other on a screen while an adjacent screen shows a remake of the performance recorded in 2017. Naked, Abramović eats a jar of honey, drinks a litre of wine, then takes a razor blade and carves a star on her stomach and lies down on a block of ice. The emotional and physical tension of watching this reaches its peak – every stroke of the razor leaving a fine line of blood on Abramović’s body is felt almost physically; this is the moment when arrogance becomes impossible, the foundations of the constructs of ability and endurance built by the mind shatter in these minutes spent in front of the screen. Moments before the razor touches her body, Abramović stands with it in her hands, concentrating, and the feeling that you, as the viewer, already know what is going to happen next makes the process of watching doubly challenging. You want to walk away, turn away, but at the same time, stay – because in this moment the story is no longer about Abramović but about you and your limits. “What is most important for me? What I give to the audience; and what I give is 150% and not 100%. 150 is more than 100. My duty is to give you all of myself, every single moment of my being, which I do. And that’s it. That’s my job.”

Abramović’s energy field is fully present and palpable in this exhibition – even the most sceptical cannot escape it. At the same time, it invites us to turn to the deepest recesses of our own body/mind/soul, to become aware of our own capacity and our own being.

This is a striking pageant of performance history that takes time and space in one’s mind to watch. But also in the body, triggering processes that are impossible to verbalise and that can only be felt/experienced/lived through. “You go through the works, some longer, some shorter. But there is also a meditative moment in this exhibition from which you come away with real knowledge of what performance art is. Because for many people, performance art is not exactly territory they are comfortable with and they don’t know what it is. But I’ve been doing this for 50 years. That’s a long time. And I can say with certainty that performance is a unique form of art. It wasn’t mainstream art for many, many years, but it finally became mainstream art. And performance is time. Once it starts, you have to be there to witness it, or, if you’re not there to witness it, video can capture the moments to be watched later. [...] Another important thing about this presentation is that I was very interested in works of long duration. Because a long-duration work of art is a really transformative form. Performing something for one or three hours is one thing. But if you’re performing something for six hours, and then for one month, and then two months, and then three months, you change. When you change, the public changes with you. If you change yourself, you can change thousands. So this is really the core of performance work – how to actually create and give an objective message to the audience, and how the audience can actually go along with you on this immaterial journey.”

Despite its retrospective nature, the exhibition is not a historical retrospective. The multifaceted nature of the works and the eternal relevance of the themes, the questions encoded in them, fit into today’s torn world as organically as in the moment of performing/creating each particular performance. In today’s geopolitical context, the symbolism of Abramović’s performance Balkan Baroque (awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in 1997) is staggeringly poignant. “This work was not just an image about the Balkan war. It was an image about Syria and Iraq and Iran. And now you can relate it to the situation in Ukraine. So this is very important. I’m just trying to figure out now how this one work of art can live many lives.”

The context of the Ukrainian war literally activates every cell of this exhibition, confirming the meaningful essence of art and its ability to become a tool with which to find answers, to find solace, and to become a kind of energetic bench on which one can rest and recharge. At the same time, it answers a question that is so very topical at the moment: What is the role of art and the artist in times of crisis. “The role of an artist in society is very important. The role of an artist in the 60s and 70s was like... the artist was kind of bohemian – not washing that often, drinking too much, sitting in the studio creating art and dreaming about being discovered. This kind of function of an artist has passed. A functioning artist’s function is to be responsible, first of all – responsible for their work, responsible for their message, and to give that kind of example of how they are to society. And also, to have a very clear voice in circumstances like this. I was the first artist who, just two hours after the start of the war in Ukraine, gave a public statement against the war and against Putin. For me, what happened in Babi Yar in 1943 is very close to my heart. We are Slavic people and I come from the former Yugoslavia; I come from that family. Both of my parents were war heroes and I know what it was like in Nazi Germany. I created a very big project in Babi Yar for the Holocaust Memorial just last year. The story of Babi Yar is incredible – in 1943, 33,000 people were killed there in just a few days. Jewish people, gay people and [Roma] – in mass graves and the Germans came and just put earth over them. Then the Russians came and poured concrete over it and created a park – but never any memorial. But then Zelensky, who is Jewish, came and created this Memorial and invited artists to participate. I was one of the artists invited, and I made the biggest non-performance project of my life, an interactive piece. I create a wall of coal 40 metres long (coal is a source of energy, fuel), and into this wall I placed 150 quartz crystals (from Brazil) at the height of a person’s head, heart and stomach. It beckons people to go up to the wall, and when facing it, your body touches the crystals and receives healing. The war also created tears, so I called it the Chrystal Wall of Crying. It was inaugurated by Zelensky as well as the Presidents of Israel and Germany. On the second day of [this current] war, a tower only a hundred metres from this wall was bombed, but the wall is still there. If this wall survives, it will serve a double purpose – against the Nazis in Germany and, now, against the Russians. This is how artists can create a message, how they can contribute to the situation. Artists have to have a clear voice about which side they are on.”

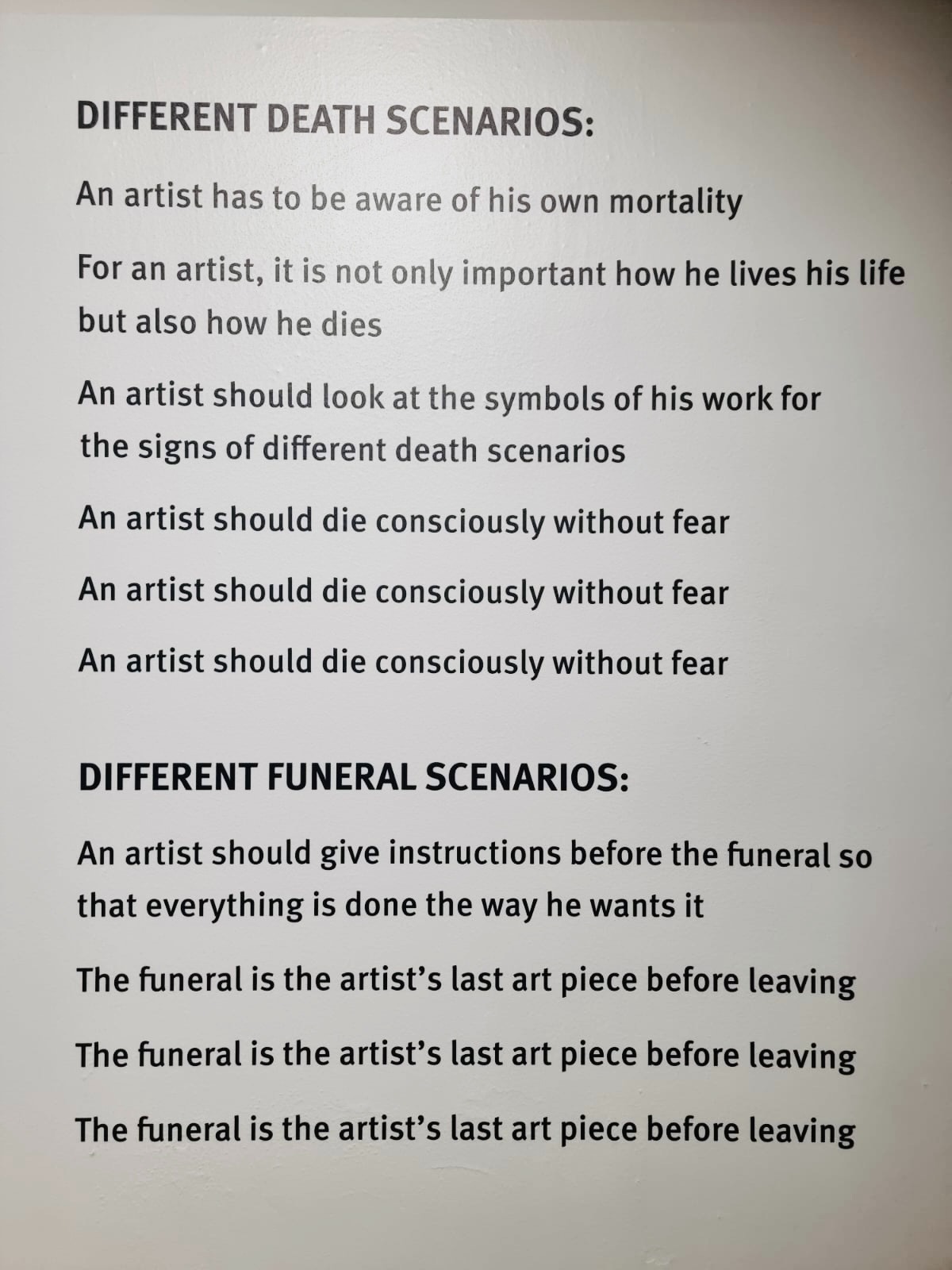

Abramović is structured and self-disciplined, in every way as precise as a surgeon’s scalpel. Marina Abramović: An Artist’s Life Manifesto is displayed on one of the walls of the exhibition (it can also be heard in the background). Asked by Arterritory if there is a difference between an artist’s manifesto and a mere human manifesto, especially given that we are all co-creators in this process called life, Abramović replies: “I really started writing it more like a human being than an artistic statement, except for a few details, like, never falling in love with another artist. (This is definitely something I advise: never fall in love with an artist. I have done it three times; such a bad decision.) And also – don’t let you and your work become a good on the art market, and don’t repeat yourself. But otherwise, most of the statements of the manifesto really apply to any human being. And I think it’s very important not only for artists but for everybody to write their own manifesto, to create some kind of borderlines, some kind of focus on morality – what you really should do and what you should not do in your life, and stick to these decisions. It’s very important.”

The artist should avoid overproduction and pollution of his art. An artist should decide for himself the minimum personal possessions they should have – says Abramović in her manifesto.

The aspect of the artist’s financial existence, both in terms of survival and creation, has been relevant at all times, and in this sense, performance is a rather complex genre. “How can you survive financially as an artist? That’s a very important question. In the 1970s, 80s, and in the early 90s, I never got any money for any of my performances – for any of my work. The idea of selling was abstract to me. I did the galleries, but I didn’t know who would ever buy this. So I taught. You know, for artists in their early years, it was very simple to make money: musicians were driving taxis, dancers were working at bars, and painters and visual artists were working at museums as guards. I mean, this is how you made money – not from your own work because that was impossible, especially if you were making work that [embodied] new ideas. Performance was revolutionary in the 1970s, but the galleries had nothing to sell. That’s why at the end of the 1970s, there was huge pressure on the market to produce something to sell. I always say all of the best performance artists became bad painters. Okay, maybe it didn’t exactly go that way for me, but I was doing different jobs. But then things changed for me.

The one thing that is interesting about performance art is that until now, performance art had never been a commodity – it cannot be a commodity. Any mid-career artist makes ten times more money by selling their paintings than I do with my video installations. Because people don’t collect videos. That’s because you have to have the right equipment, you have to show it, and if there’s no electricity, you don’t have the work. I mean, it’s so much easier if you have a nail on the wall and you just put the painting on the wall to sell it. I’ve spent almost 30 years of my career teaching in order to support myself. But now I’m 75; maybe I’m finally getting paid. But it took a long time.”

50 years is a relatively long career. But existence has no linear time, only a present form that includes the past and the future. Consequently, Marina Abramović’s memory of being also embodies the presence of being. Hers and ours.