Seventh Continent on the Bosporus

30/09/2019

16th Istanbul Biennial of contemporary art, thanks to its curator Nicolas Bourriaud, has been given an intriguing, slightly futurological-sounding title ‒ The Seventh Continent. This, however, is not a reference to anything like a futuristic breakthrough; it is simply a recognition of the fact that there are several million tonnes of plastic floating around in the Pacific Ocean alone. The Seventh Continent is something more like a statement of an existing reality, namely, unprecedented domination of the Anthropocene factor, unwitnessed since the beginning of the mankind. The curator believes that the appearance of this continent on the map of the Earth cannot be compared to the discoveries of Columbus: ‘It is [a land] that we ourselves have created, without even being aware that we were doing it. And what we have created is exactly what we did not want. A continent composed of everything we have rejected, it is the ultimate symbol of the Anthropocene era.’

It was Bruno Latour in his Politics of Nature (first published in France in 1999) who marked the birth of a fundamentally different interpretation of these two notions. Ecology as politics is trendy at the moment, so the announced subject is quite topical and not without a hint of political intrigue. Although one would have expected a somewhat different concept from Nicolas Bourriaud, the theorist of the ‘art of interaction’, perhaps something related to contemplation of this phenomenon that has been fascinating artists and critics for the last 25 years. Nevertheless, it was from the geopolitical point of view that Bourriaud approached defining the problem of the seventh continent, because Istanbul as an intersection of the paths of history, a border city that belongs to two different worlds at once, could become a very suitable territory for reflections on the subject.

Eva Kot'atkova. The Machine for Restorating Empathy. 2019

If you view the seventh continent as the world of contemporary art, Istanbul, a relative neophyte in this game, could be considered a new territory of this expanding universe. September events alone ‒ obviously coordinated with the opening of the biennial (marking its 30th anniversary this year) ‒ speak for themselves.

Firstly, it was the Istanbul fair of contemporary art, which ran between 12 and 14 September. Secondly, it was the opening of several new centres ‒ museums, exhibition spaces capable of reasserting the city’s ambitions to serve as a bridge between continents not only in the past, but also in the present and the future. The main project of the biennial was housed in the freshly-completed building of the Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture. Practically at the same time, the new building of the Vehbi Koç Foundation ‒ Arter (designed by the London-based Grimshaw Architects) ‒ and Tekfur Palace, the museum of Ottoman art, opened in Istanbul. Over the next few months, a number of other new art spaces will appear in the city, while the grand project of the new museum of contemporary art, Istanbul Modern, is being designed by the world-famous architect Renzo Piano. And literally on the eve of the opening of the biennial, a huge private museum of contemporary art ‒ Odunpazari Modern ‒ was unveiled in the Turkish city of Eskişehir. Its founder, the Turkish architect and collector Erol Tabanca, had asked the fashionable Japanese architect Kengo Kuma to design the project.

The events of the biennial were hosted by three main venues: the new building of the upcoming Museum of Painting and Sculpture, the Pera Museum and Büyükada Island.

Contemporary art since the times of Duchamp has been residing on said ‘seventh continent’. You could say that it was long before its actual formation that the contemporary art world started actively exploring and appropriating objects and forms, the production and circulation of which already took on a threateningly preventive character back in the era of the first avant-garde. Today’s artists work with this new materiality like with a second nature. Tsunamis of trash, various forms of recycling sweep over museums and galleries in waves of mainstream, leaving behind a mass of objects that settle like dust on the Earth’s orbit. Unification and seriality dictated the general character of the forms of ‘flora’ and ‘fauna’ of the seventh continent, the expansion and collecting into a whole of which is taking place in the era of atomisation of consciousness, disappearance of ideas that unite people and, as a result, dissociation of human beings.

Essentially, Nicolas Bourriaud had come up with a very ambitious project that would see him review the traditional models of examining the history of arts. He believes that in the age of the Anthropocene (a term he uses to denominate a fundamentally different stage in the history of Earth and history of the human race), art establishes different forms of interaction between man and the world of nature, society and himself. In the past, from the time of the Fayum mummy portraits through the 19th century, it was the Biblical model ‒ man and the world of nature; the object and the atmosphere; the hero and the background ‒ that dominated the history of art; in the Anthropocene this model is replaced with another, one where the background triumphs, while the relationship of duality (man ‒ God; living ‒ dead’; man ‒ woman; nature ‒ civilisation, etc.) gives way to plurality, a landslide of disorderly connections between various forms of the natural and the social in which man loses his privileged status.

And indeed, what is that keeps contemporary art busy these days? It is consistent criticism and exposure of various forms of bullying and domination, on every level ‒ like in the children’s game of ‘don’t say yes or no’. Moreover, according to Bourriaud, the very understanding of art as an area of manufacturing or producing certain exclusive objects, superior in form, has been completely changed. The artist can now simply join a discourse; he is a driver, directing the traffic of natural/cultural forms and relations, a cryptologist, an interpreter into the language of art, translating from one area of reality to another.

Chales Avery. Untitled (Ninth Stand with Urchins). 2017

And that is exactly why the works represented at the biennial share a drive to find various kinds of isomorphism, transformation of forms of this infinite seventh continent. Bourriaud believes that its location cannot be imagined as a separate part of the earth, although its actual size exceeds the area of Turkey or, for instance, France, several times. The seventh continent is everywhere; this is the product of human activity in the age of Anthropocene. It is a global circle of a multitude of forms, images, entities, relationships existing in perpetual exchange, overlapping, merging, division, metamorphose, etc. Interestingly, the main exhibition was supposed to be housed in the territory of the former Istanbul shipyard; the idea had to be abandoned when asbestos, a toxic substance hazardous to the visitors’ health, was discovered there. Bourriaud’s initial plan to present the works in the shape of two spirals, one inside the other, could not be realised.

As a result, the works were housed in the just-finished building of the upcoming Museum of Painting and Sculpture, reminiscent of a penitentiary institution rather than an exhibition space. The grey concrete of the heavy beam structures and the grey steel walls, dividing the floors into individual separate compartments, define the visual perception of the project as a whole. It is a fragmented space, where every work seems to reassert the curator’s text in which the seventh continent is more like an archipelago of islands, separate and isolated statements. If we use the site-specific metaphor, the viewer finds himself in the underground, where each cave hides another treasure, and for each of them you need the sacramental code (Ali Baba’s ‘open sesame’). This effect, which works in favour of the concept of the project on the whole, makes the general tone of artistic statements seem somewhat affected and theatrical and, to an extent, game-like: another space, another amusement show.

And perhaps the best example in this sense is a work that could be described as the quintessence of the general idea behind the project ‒ Mica Rottenberg’s Spaghetti Blockhain video (2019), a funny, surreal, witty and observant statement by an artist whose works are a spectacular and at the same time profound immersion in the world of mass culture. She captures Tuvan throat-singing women, the virginal Tuvan nature, and places these primordial, archaic codes in the centre of a hexagonal kaleidoscope that keeps collapsing until an autonomous game starts in each of the parts: there are certain reactions and metamorphoses of natural and synthetic materials that disappear in front of the viewers’ eyes. In the Tuvan yurt, however, we can notice mining servers for obtaining cryptocurrency, and that establishes the paradoxical contemporary logics that cancels the differences. In this absurdist kaleidoscope, images are short-lived, collapsing and giving way to others ‒ extracting sounds from the human throat, potatoes from the ground, bitcoins from virtual reality, creating fake visual and audio effects.

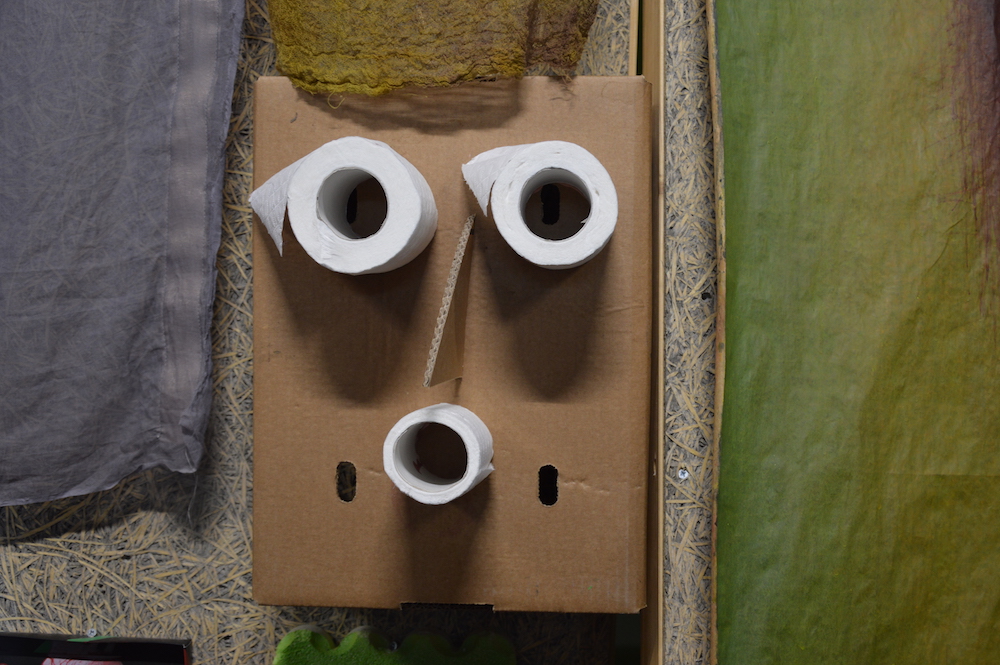

Güneş Terkol & Güçlü Öztekin. Worlbmon. 2019

Duo of young Istanbul-based artists, Güneş Terkol and Güçlü Öztekin, imagined a space of total installation, creating an immersion into the theatricalised world of trash. Their ‘nest’, constructed from corrugated cardboard, plastic, fabric and other materials picked up all over the place, is made like an immense collage of everything in the world and reminds of some kind of pataphysical archive of an urban lunatic. Moreover, this random selection does not seem like a collage created by accident: all these variously-sized images, from the graffiti murals to the tiniest artist’s books, open for the viewers to fill them, are linked by being processed, passed through the filter of painting. This generation, already grown up on the dump of the global iconosphere that is the seventh continent, an immense rhizomatic net enveloping the world of material and virtual reality, fits organically into the context of the biennial. And they have created their own space for recreation, dialogue and live action here.

Güneş Terkol & Güçlü Öztekin. Worlbmon. 2019

The forest of images surrounding man is partly determined by the capitalist economy, always in need of constant expansion and multiplication of the nomenclature of goods and images. Simon Fujiwara’s It's a Small World (Slum) (2019) presents a critique of the world of consumption. He has constructed models of social institutes, on the one hand, as individual amusements, in each of them using a popular image borrowed from mass culture, and, on the other hand, as panoptic machines of control, where entertainment turns into a form of veiled coercion and violence, masked by a pretty media picture. And so human life successively appears like huge grotesque toys and metaphors of social relationships ‒ school, factory, temple, hospital, forum, supermarket, museum, slums, brothel, prison, cemetery…

The seventh continent does not spread just throughout the present and the future. With its vast emanations, it also expands into the past, into history. Regarding this, there are several statements at the exhibition where the artists mystify the past, rewriting it all over, as if detecting, bringing out the genome of the seventh continent in the course of history. Marguerite Humeau has placed in a dark, dark room her version of a Neolithic Venus as Venus of Courbet (2018). A bio- and anthropomorphic creature, whose fluid, still shaping forms are reminiscent of a tree, a tongue and a vagina simultaneously, depicts a woman at an early stage of the process of transforming from a primate into a human being. Why is it a woman? Because, according to the artist’s mythology, it was a group of women who, having found and consumed some kind of psychotropic substance, started a process of neurobiological mutation.

Suzanne Treister presents her own take on the birth of natural and social forms, mysteriously interlinked with the world of psychoactive plants. Her HFT The Gardener (2012‒2015) is a fictional story of a Hillel Fischer Traumberg, a banker who has become an artist, an outsider. He, in his turn, is actually a vision experienced by the dormant consciousness of HCE, a character in James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, a work written in a non-existent language as an attempt to create the effect of being immersed into nocturnal consciousness. The technique Joyce used to create this text is called semiotic hybridisation, and it is this Babel-like mixture of languages that attracts the artist. Traumberg is a techno-shaman; he draws diagrams, studying the influence of psychotropic plants on the world of form, juxtaposing the iconography of shamanic cultures with the indices and data that circulate in the world of high-frequency trading. Thus, the artist uses the fictional character to try to create a new combined language that would allow someone to comprehend the invisible forces that rule the course of history and power and where Traumberg’s hallucinatory visions have been presented in the shape of a systematic catalogue.

Archaeology of the future interests Müge Yılmaz. In his Eleven Suns – Vulture (Gyps) (2019) the artist has created the images of eleven suns, arranging on the walls silhouettes that are reminiscent of ancient petroglyphs. In the future, the planet will change so much that it will become difficult to find water. That is why there is a ritual oval from stones, coral skeletons and sponges alternating with plastic containers filled with water in the centre of the installation.

Norman Daly. Civilization of Lihuros. 1972

At Pera Museum, tribute has been paid to the American artist Norman Daly (1911‒2008), who created his Civilization of Llhuros back in 1972. He made up a whole world of a just-discovered culture, presenting it in the shape of ‘archaeological artefacts’, texts and music. Locked in glass showcases, these objects, constructed from found mass-produced items, are displayed in a manner that is stylised to remind of a strict historical exhibition dedicated to an ancient civilisation (Egypt, Mesopotamia, Incan Empire).

In the context of the concept of the biennial, this 1970s project reaffirms the idea of recycling as a possible way of using combinatorics and transforming the new material reality into a coherent self-sufficient language that can be compared to the ancient civilisations existing in the past. The same museum also houses the virtuosic drawings by Ernst Haeckel (1834 – 1919) – a naturalist, physiologist, teacher of anatomy and illustrator, founder of a whole new direction of scientific knowledge, ecology ‒ the study of the relationship between living beings and the environment of their existence. Executed with scrupulous and pedantic meticulousness, the drawings of various living beings, sea creatures and microorganisms seem more than topical today, when artists in their masses turn to the immense world of biological life forms. Pera Museum has also accommodated another contemporary mythologist who has invented a utopian island civilisation ‒ in his Untitled (Ninth Stand with Urchins) (2017), the British artist Charles Avery has imagined the port city of Onomatopoeia. It is a large-scale installation staging a fish market, where glistening and glittering snakelike eels and jellyfish of multi-coloured glass have been placed in plastic tubs and buckets that could have been borrowed from any of the fishmonger’s stands on the Bosporus. Mixing everyday reality with fantasy, the artist in his work explores the problem of xenology, a term extremely important for Nicolas Bourriaud, as a concept denoting plurality of other, alien creatures, completely unlike anything in our worlds.

Eva Kot'atkova. The Machine for Restorating Empathy. 2019

Unlike the scary and repulsive, albeit humorously intended world of Avery, Eva Koťátková imagines a kind tactilely complementary world of fantastic utopia. In the building of the MSFAU Museum of Painting and Sculpture, she has created a large-scale installation that incorporates various objects, prints, sewing patterns and a video ‒ The Machine for Restoring Empathy (2019). In this slightly infantile utopian land, the artist would love to live in a world where animals are not divided into edible and inedible, and relationships are built on the principle of love, not convenience. The patterns, laid out on the floor, seem to invite for a session of communal work, creating a sense of co-operative togetherness, where the viewer can become an empathiser in the process of creating an artwork. Koťátková sews together props, fragments of various living creatures and humans ‒ not the actual body parts but pieces of clothing: the patterns are made from fabric, and a jacket or a shirt has been attached to a rag fish’s tail.

Tala Madani from Iran is the author of Corner Projection (2019), a work about a generation raised on fascination with the magic of cinematography as a projection of light. Light, with the help of which we reveal the world, is also used as zombifying propaganda.

Three animation films harshly and sarcastically, using the aesthetics of a cartoon commercial, attack violence, an instrument of which is film projection. People without faces and identities exist in a state of acquired helplessness, while their manipulators stand on the other side of the film projector. In one of the clips, criticism of power relations in the society is visualised as a giant phallus, swatting the tiny humans like a fly flapper.

Karakrit Arunanondchai (Thailand) presents a video entitled ‘with history in a room filled with people with funny names 4’ (2017), intertwining three stories ‒ his grandmother suffering from dementia; Americans protesting again Trump’s election, and Thai people mourning the death of their emperor. The simultaneousness of these three tracks in history is supplemented by the author’s philosophical reflections on how we understand history, which is so easily rewritten from a position of power, and how important are various scales of history. Near the end of the film, a drone named Chantri appears ‒ a technological analogue of a reborn cyber soul. Buddhist philosophy and Marxism; the Annales school and faith in the technological potential of the man of future ‒ all of this form certain horizons of meaning inherent to the contemporary man who is involved in politics and reflects on his place in this world, on historical memory and oblivion.

Jared Madere. Pavilion du Voyagerus. 2019

Jared Madere (New York) in his installation Pavilion du Voyagerus (2019) refers to images of mass media ‒ musical theatre, reality shows, talent shows ‒ creating with the help of photo wallpaper, collages and objects an effect of immersion in an environment of trash and glamour. The hitch-hiking angel behind the wheel of a glossy car with a Union Jack reminds more of a demon from the hell, but the trick is ‒ we believe that it is an angel, because everything seems so fascinating in this world of glittering soap bubbles. Photographs of local people, found on Instagram, tagged #Istanbul and attached to banners of funny collages made from other Internet-sourced images, are not connected in any way. The total spectacularity of the mass media society and the infinitely manipulable picture created by virtual reality raise the question of trusting a world full of endless temptations. Talent TV shows teach that we must by all means assert ourselves at the expense of others who are not so fortunate. To counteract this, the artist has created the performative part of the work, a smiling contest, in which points are given to those who encourage, not humiliate, their ‘rivals’.

The choice of Büyükada Island (the largest of the Princes’ Islands in the Sea of Marmara) as one of the venues of the biennial was apparently inspired by the concept of the seventh continent as an archipelago. The distance from the city centre, the status of the islands as a resort, the opportunity to go on a sea voyage ‒ all these things already guarantee the necessary effect of detachment, of escaping from the boundaries of the stressful urban rhythm to the ‘lap of nature’.

Hale Tenger. Appearance. 2019

Hale Tenger (Turkey) in her landscape installation Appearance (2019) demonstrates a minimum of interference with the space around her. The artist tactfully settles into the environment with which she works. In this garden, an apple-tree grows among many other trees. Black obsidian mirrors and little black ponds ‒ water mirrors ‒ evoke meditatively contemplative disposition. The need to see one’s reflection ‒ that is the flickering line that separates man from nature. Looking into the black mirrors, man sees himself and foliage, a passing bird, ruins of a building; nature just looks at itself. The contours of the image are blurry, and that creates an effect of the subject‒object relationship being cancelled. The tree speaks the language of poetry; a female voice recites verses. The black saucers of reflections like portals to another distant and beautiful world, resonating with the dark eye sockets of the abandoned house, remind of a paradise lost.

Post-humanist paradise of the future ‒ that is one possible interpretation of the video by Ursula Mayer (London), entitled The Fire of Knowledge Burns to Ashes All Karma (2019). A real-life person ‒ the trans model Valentijn de Hingh ‒ floats in a state of weightlessness waiting, until the player starts to direct her. She ‘freezes’ and keeps repeating the same movement over and over again, staying in the blissful state of weightlessness ‒ that is how our future is going to look like, when there will be no need for us to work. At that, our actions in this work vacuum will become devoid of any value. A hybrid model of reality, an icon/avatar, in which the island-like transgender human amphibian marks the flickering boundary of fiction as a dawning reality. Contrasting with the languishing virtual image by Ursula Mayer, the sculptures in Gorgon’s Playground (2019) by another London artist, Monster Chetwynd, have been made in a markedly slapdash manner. These are openly prop-like figures, cleverly arranged in front of the entrance of one of the abandoned houses. Like materialised spirits of the location, these hybrid creatures offer a tongue-in-cheek play on the chimeras of the mass media consciousness: a pig, a caterpillar, a crocodile and batman-superman have all been humanised, like in children’s cartoons.

Ursula Mayer. The Fire Of Knowledge Burns to Ashes All Karma. 2019

To conclude this review, it should be noted that the situation that arose as a result of forced relocation of the main exhibition from a spacious shipyard space to the rigidly structured museum gallery was not part of the curator’s plan. Nevertheless, surprisingly it was this change that turned out to embody the spatial model of the same concept of an atomised world of plurality for over fifty artists that Bourriaud, looking for help in mathematics, referred to as omega+. And it is, of course, a striking contrast with a completely different experience of space, one born out of feeling the air of Hagia Sophia surrounding you or the sight of Sinan’s mosques that present not a horizontal but a vertical way of facing the world.