Modigliani

04/12/2017

Tate Modern, London

November 23, 2017 – April 2, 2018

Just opened at Tate Modern is the largest exhibition of works by Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani to have ever been shown in the UK, including paintings that haven’t been publicly shown since 1917.

In the art world, the name Modigliani – who along with Picasso, Munch, Warhol, and Bacon is part of the so-called ‘$100 million club’ – is also associated with a rather large number of forged reproductions. A broad exposé of the issue published in Vanity Fair last summer included the following quote from a Paris art dealer: ‘The drama here is that I could find a Modigliani in an attic tomorrow, with a letter from Modigliani attached to it, and people would still hesitate.’

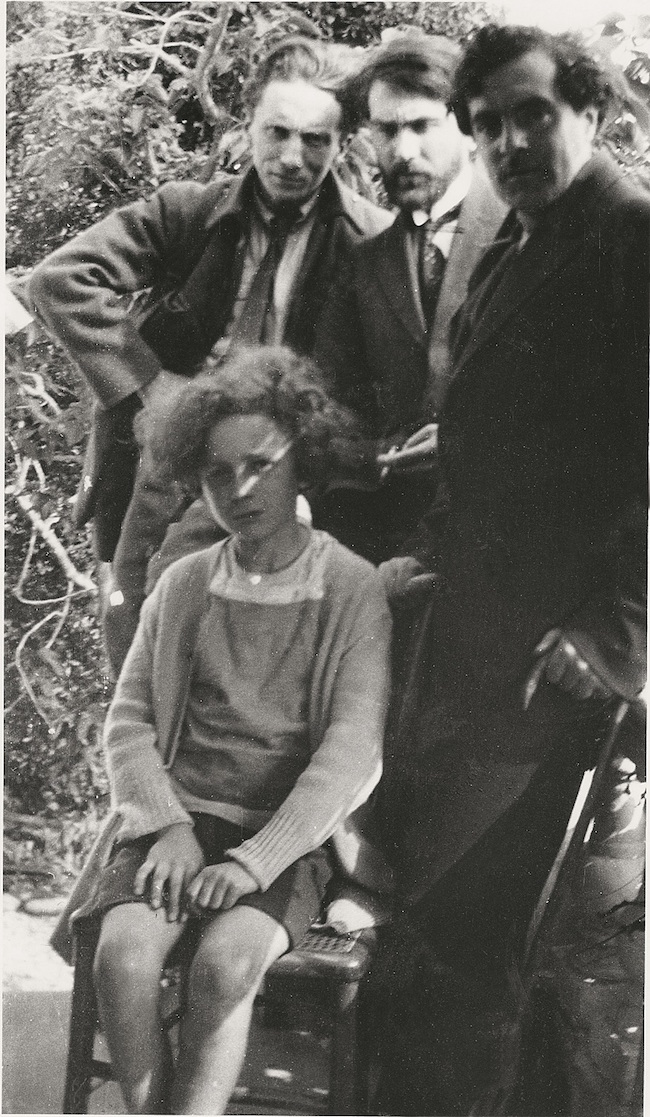

Amedeo Modigliani, Léopold Zborowski, Anders Osterlind and Nanic Osterlind. Haut-de-Cagnes, 1919. Association Anders Osterlind

Yet Modigliani forgeries are not the focus of this exhibition; it is about how the young Italian, born in the Tuscan port city of Livorno, arrived in Paris at the start of the 20th century and developed his own very powerful and individual style of painting, one that cannot be confused with anyone else’s. Furthermore, he was well received by the most influential creative figures of the time – Pablo Picasso, Max Jacob, Juan Gris, Constantin Brâncuși, Diego Rivera, and Jean Cocteau, among numerous others. More than 100 works are on view in the exhibition, including paintings, sculptures, and drawings, one of which depicts the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova. What makes this exhibition unique, however, is the added attraction of the virtual reality experience ‘The Ochre Atelier’; it allows the viewer to ‘visit’ Modigliani’s last studio in Montparnasse, which has been reproduced according to photographs and his friends’ memories and writings. It even has such details as a burning cigarette in an ashtray and an open window through which you can hear it raining down upon the roofs of Paris. And like science fiction come to life, by focusing in on certain spots, you can turn on the voice of a Tate Modern art historian reading commentary, memories and quotes about the studio from letters written by Modigliani’s friends. One can also see in the studio two of Modigliani’s last works – a portrait of his lover Jeanne Hébuterne (1919), and on an easel, an unfinished self-portrait; both works can be seen in real life in the exhibition’s last room, titled An intimate circle. After having experienced this, the clichés about artists living in poverty no longer seem like mere clichés.

Self-Portrait as Pierrot, 1915. Oil paint on cardboard, 430 x 270 mm. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Portrait of a Young Woman, 1918. Oil paint on canvas, 457 x 280 mm. Yale University Art Galle

The exhibition also begins with a self-portrait of Modigliani. Painted in 1915, he has depicted himself as the tragic clown Pierrot, back then a very popular stock character of film and theatre who embodies sadness and melancholy, but also wishes to be a great comic performer. A similar motif also weaved itself throughout Modiglian’s life. The work was painted after Modigliani had spent almost ten years in Paris, and, in a sense, serves as a touchstone of the moment that Modigliani was finally ready to announce himself.

Cagnes Landscape, 1919. Oil paint on canvas, 460 x 290 mm. Private Collection

Early on, a great impression was left on Modigliani by a retrospective of works by Paul Cézanne presented at Salone d’Automne in 1907, a year after Cézanne’s death. Salone d’Automne was Paris’ largest annual contemporary art exhibition of the time, and is a staple in the biographies of practically every French impressionist and modernist. Modigliani’s The Beggar of Livorno is especially reminiscent of Cézanne’s signature style, yet he wound up under the spell of many other artists, too, Van Dongen and Toulouse-Lautrec among them. Modigliani arrived in Paris, which was roughly the centre of the creative cosmos at the time, with a very good foundation in the Italian school of drawing and a rich cultural background. Perhaps this is what allowed him to experiment, yet not become too attached to any of the ideas being batted around at the time (including cubism), and to continue to look for his own style. Modigliani’s 1913 portrait of his first art dealer, Paul Alexandre, is his first piece in which one can make out the poignant inklings of what would later become his signature style – the long, stretched-out necks and almond-shaped eyes of his portraiture subjects.

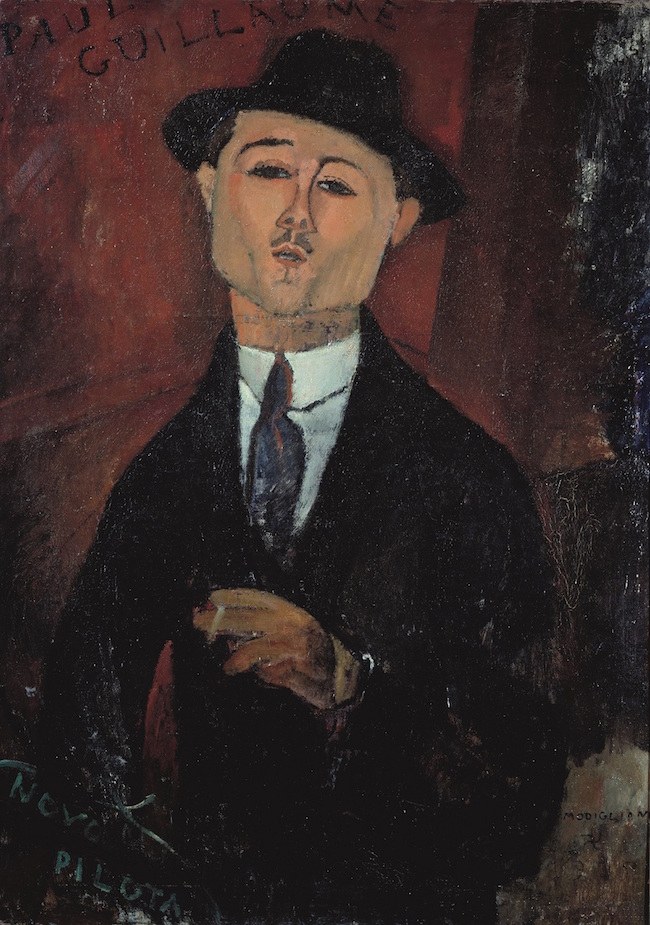

Portrait of Paul Guillaume, Novo Pilota, 1915. Oil paint on card mounted on cradled plywood, 1235 x 925 x 100 mm. Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris. Collection Jean Walter et Paul Guillaume

A year later Paul Guillaume became Modigliani’s dealer, and the Tate Modern exhibition includes four portraits of the gentleman – three paintings and one drawing. Although Guillaume was younger than Modigliani, he had a substantive role in Modigliani’s career. Guillaume was very interested in African sculptures, and emphasised that they were an art movement in themselves rather than just an ethnographic aspect. Together, Modigliani and Guillaume visited the Trocadero Ethnography Museum and the Louvre. The clean lines and shapes of African art attracted many young artists at the time, including Modigliani. Guillaume was a notable art collector as well, and died young and under suspicious circumstances. Rumor had it that his wife Domenica had murdered him, and in order to escape prosecution, had to relinquish Guillaume’s entire collection.

Head, c.1911. Medium Stone, 394 x 311 x 187 mm. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Lois Orswell. © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Woman's Head (With Chignon), 1911-12. Sandstone, 572 x 219 x 235 mm. Merzbacher Kunststiftung

The Tate Modern exhibition also features a sizable number of Modigliani’s sculptures – nine of the 28 that are known. Under the influence of Brâncuşi, Modi began to dabble with sculpture in 1909, and Brâncuşi even helped him find a suitable studio. At one point, Modigliani was so into sculpture that he was even introducing himself as a sculptor. Shortly before coming to Paris, he had studied sculpting at Carrara, the site of Italy’s famous vein of marble, so the art form was far from foreign to him. Modigliani’s sculptures were also exhibited at Salon D’Automne in 1912, but they did not garner much attention. After a few years, he left the genre completely by the wayside; no one really knows why. Modigliani spent most of his life ill with tuberculosis, and perhaps the marble dust was too irritating to him; maybe the raw materials were too expensive, or maybe he had a too clear vision of what he wanted to create and the stone simply would not yield. Or, it just could be that he abandoned sculpting after Brâncuşi remarked that it is much easier to sell paintings. No matter the true reasons, Modigliani’s sculptures had a notable influence on how his painting would develop after 1913/1914.

Beatrice Hastings, 1915. Oil on paper, 400 x 285 mm. Private Collection

Modigliani painted most everyone he knew – his friends and closest contemporaries – and he tried to capture and bring to life each person’s unique and distinctive characteristics. He was surrounded by artists, poets, writers, thinkers and philosophers; one of his friends was Gaston Modot, a star of silent cinema. A whole room of the exhibition has been devoted to Modigliani’s portraits of these people. Three of them are of the English writer and poet Beatrice Hastings, who was Modigliani’s lover for a time. Much has been written of their affair, and Hastings herself wrote detailed descriptions of her life with the artist. She had much to say, even of their first meeting: ‘Not impressed at all.’ Modigliani drank brandy and smoked hashish. Actually, he drank and took drugs quite a lot, which undeniably impacted both his behaviour and early death. Another work in this room worth pointing out is the portrait of the French artist and writer Jean Cocteau; Modigliani lightly caricatured his subject in an attempt to capture Cocteau’s pointed vanity. Cocteau was an influential yet not very loved character, and always thought very highly of himself. Cocteau even paid for the portrait, yet didn’t take it with him, saying that there wouldn’t be room for it in the taxi...but he never sent for it.

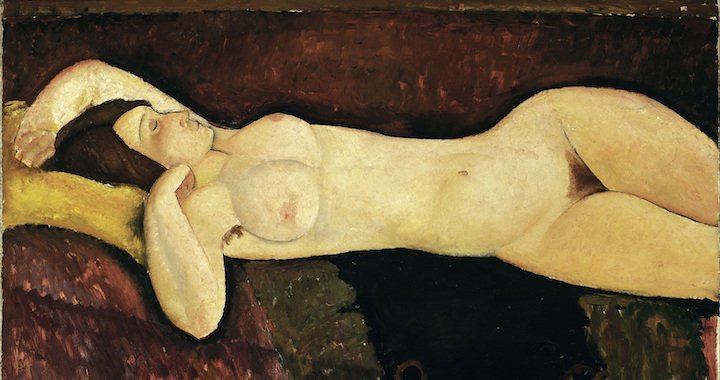

Nude, 1917. Oil paint on canvas, 890 x 1460 mm. Private Collection

Quite possibly, Modigliani’s painted nudes make up the quintessence of the exhibition. About a third of them have never been shown in the UK before, and some were last viewed by the public more than a hundred years ago, when Modigliani was still alive. Clearly, the curator had quite the assignment here, and almost half of the pieces come from private collections. Modigliani’s nudes could be said to be his most well-known works, yet in terms of numbers, they make up only a tenth of his paintings. Nudes were very popular among buyers at the time, and Modigliani began to paint them on the advice of his dealer, Léopold Zborowski, in order to...break into the art market. And he was right; Modigliani’s sales rose. In 1917, the Paris gallerist Berthe Weill (who was also the first to show Picasso’s works in her gallery) organised Modigliani’s only solo show. But things didn’t quite work out for Modigliani. Weill’s gallery was on Rue Taitbout, right across the street from a police station. When one of Modigliani’s paintings was put up in the gallery’s window to draw people in, the police promptly shut down the exhibition, ordering Weill to ‘take down all that filth!’. The works on view at the Tate Modern were painted during the First World War, a period during which the role of women was quickly changing. Women began to wear their hair short, and used cosmetics. They worked and earned their own money, and they chose to pose for pictures in exchange for money. A large room has been set aside for these works because they require a lot of space. They are intrinsically sensual, challenging, dominating, and courageous...because the women portrayed are courageous. It is not their nakedness but rather how their character and the look in their eyes has been illustrated that draws one to them. The first two works in this room make for a strange couple – the same woman, clothed in one painting (L’Algérienne, 1916), naked in the other (Nude on a Divan (Almaisa), 1916); regardless of how she is depicted, she doesn’t lose her powerful personality for even a moment.

Seated Nude, 1917. Oil paint on canvas, 1140 x 740 mm. Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, Lukasart in Flanders. Photo credit: Hugo Maertens

As Paris was being bombarded the following year, in 1919, Modigliani’s health also swiftly deteriorated; Zborowski decided to send him south, to Nice. Modigliani went there with his latest lover, Jeanne, and other artists. Once there, he returned to portraiture, painting his friends and landscapes, and discovered a completely different palette of colours – one with much warmer and lighter tones. He also returned to Cézanne, who had so greatly inspired him when he had just been starting out.

Jeanne Hébuterne, 1919. Medium Oil paint on canvas, 914 x 730 mm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Modigliani in his studio, photograph by Paul Guillaume, c.1915. ©RMN-Grand Palais (musée de l’Orangerie) I Archives Alain Bouret, image Dominique Couto

The exhibition comes to a close with the portrait group An intimate circle – besides portraits of his dealer Léopold Zborowski and his wife Anna, the rest are all of his beloved Jeanne, who died shortly after Modigliani by jumping out of a window and killing both herself and her unborn child with Modigliani, which would have been their second. In every single one of these paintings, Jeanne is depicted surprisingly differently – from as a young woman (they met in 1916) to her second pregnancy. They are very delicate, fine, and melancholic portraits. The circle closes with Modigliani’s self-portrait, left on the easel and covered with a white cloth.

Boy in Short Pants, c.1918. Oil paint on canvas, 997 x 648 mm. Dallas Museum of Art, gift of the Leland Fikes Foundation, Inc. 1977

The Little Peasant, c. 1918. Medium Oil paint on canvas. 1000 x 645 mm. Tate, presented by Miss Jenny Blaker in memory of Hugh Blaker 1941

British artist John Myatt (who specialised in Modigliani forgeries as well as fakes of Braque, Matisse, and Chagall, and did prison time for it) recalls the first time he saw Modigliani’s works in a travelling exhibition while a student in the 1960s: ‘I can remember standing there and thinking, “What a superb line”. The speed and confidence of the line almost made me shiver.’*

Modigliani painted fast. A painting would be finished in a few days, sometimes even hours.

The exhibition’s curating team consists of: Nancy Ireson, Curator of International art, Tate Modern; independent curator Simonetta Fraquelli; and curating assistant Emma Lewis.

*From Modigliani. A life (2011), by Meryle Secrest