From the Kitchen to the Museum of Modern Art

Anne Neimann Clement

25/10/2013

"Soundings: A Contemporary Score"

Museum of Modern Art (MOMA), New York City

Untill November3, 2013

Sound, as an art medium, emerged during the 1960s. In the spirit of counterculture and revolution, artists were experimenting with art that was intangible and difficult to commodify and collect. Unconstrained by the financial expectations of commercial galleries, small nonprofit artist-run exhibition spaces sprouted up in cities the world over. In these new venues, viewers became participants in new kinds of site-specific and performance-based art. Artists picked up electric guitars and made music with the same three analogue chords that were being strummed by their counterparts in punk rock bands. The distinctions between visual artists and musician performers blurred, as young artists interested in sound were as likely to study computer programming and music composition as they were painting, sculpture, and multimedia.

Not only in New York, but also in cities such as Stockholm, London, Milan, Kobe, and Melbourne, art centers known as “alternative spaces” were emerging, welcoming the evolving sonic arts. A prime example is the Kitchen, which, since opening in Manhattan’s SoHo in the early 1970s (it has since moved to Chelsea), has presented visual art, dance, and experimental music, often in combination. Small alternative spaces still thrive, largely in the low-rent peripheries of cities, and continue to showcase emerging sonic practices, but today, we find sound in one of the world's finest museums of modern art – MOMA. "Soundings: A Contemporary Score" is the museum's first exhibition dedicated to sound art.

Since the early 1990s, museums all over the world have incorporated video and media installations, and by extension, sound art, into their programming. This expansion of the range of art shown by museums has contributed to what is now a widespread acceptance of time-based media installation as a collectable art form. As media art has become the default mode for many artists, sound has moved up through the ranks, to be recognized and exhibited as an art form in its own right.

MoMA's first major exhibition of sound art presents work by 16 of the most innovative contemporary artists working with sound. The exhibition is organized by associate curator Barbara London, and includes artists from both North and South America, Europe, Asia and Australia. These artists approach sound from a variety of disciplines. Some contribute with architectural interventions, or spatial installations; others, with visualizations of inaudible sound; some – with field recordings exploring the sound within or outside the museum; while still others convey sound visually.

It All Begins with a Bench...

If you don't visit the Museum of Modern Art very often, you might not notice that the comfortable padded seating outside the third-floor restrooms is missing. In its place, you find a familiar, yet displaced sight: a 10-foot wooden subway bench installed by the New York-based sound artist Sergei Tcherepnin. For a moment, the visitor is transported to a subway platform where a train is approaching. The experience of listening becomes physical and embodied as the listener begins to feel a faint bass rumble, and soon, both the bench and the listener’s body tremble. The piece, "Motor-Matter Bench," marks the entrance to MOMA's first group exhibition dedicated to sound.

Sergei Tcherepnin (American, b. 1981). Motor-Matter Bench, 2013. Wood bench, amplifier, and transducers. Photo: Mie Dinesen

An Interactive Wall of 1,500 Speakers

You might miss the discrete "Motor-Matter Bench" in the stairwell outside the gallery, but Tristan Perich's (American, born 1982) Microtonal Wall, placed in the entrance to the gallery, is impossible to overlook. Inspired by math, physics and computer codes, Perich creates a contemporary composition of depth and complexity. Microtonal Wall consists of 1,500 tiny speakers, each with a 1-bit processor emitting a different microtonal frequency. The speakers are arranged in a grid, with low-pitched sounds on the left graduating to high-pitched on the right, and they are mounted on a twenty-five-foot-long panel. What one hears depends upon where one stands in relation to the piece, which spans four octaves. Up close, distinct tones from individual speakers can be detected; at a short distance from the center, the sounds blend into a uniform mass; and as listeners proceed from one end of the piece to the other, they progress through different tonal fields, each eliciting its own range of psychic and emotional responses.

Tristan Perich: Microtonal Wall, 2011. 1,500 1-bit speakers and microprocessors, aluminum. Photo: Mie Dinesen

4 Rooms in the Zone of Exclusion, Chernobyl

The Danish artist Jacob Kirkegaard (born 1975, resident in Berlin) has contributed with the sound and video installation "AION"*. The work is a portrait of four abandoned spaces inside the so-called “Zone of Exclusion” in Chernobyl, Ukraine; a dripping swimming pool, a ruined concert hall, a mold-infested gymnasium, and an old village church. After the accident at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant on April 26th, 1986, the local population was evacuated by the Soviet military. The former homes, meeting places and recreation centers were declared contaminated territory – in fact, they will remain uninhabitable for thousands of years. Two decades after the disaster, Jacob Kirkegaard visited the exclusion area with his recording equipment.

The sound of each room was evoked by an elaborate method: Kirkegaard made a recording of 10 minutes and then played the recording back into the room, recording it again, then repeating the process ten times. As the layers got denser, each room slowly unfolded its own unique drone of various resonant frequencies. This method is inspired by Alvin Lucier's work "I am sitting in a room", from 1970. Lucier recorded his voice in a space and repeatedly played his recording back into that same space. In Kirkegaard's work, however, no human voice can be heard. During the recordings, he left the rooms to wait for whatever might evolve from the seemingly silent spaces, recording the voice of the rooms themselves. With each new layer, the subtle sounds of the room were enlarged and deepened until they finally turned into one humming sound with many overtones.

For the visual representation of the four rooms, Kirkegaard explored a variety of similar techniques, working with layers, overexposure and video feedback parallel to his acoustical method. As was done with the sound, all video was recorded in the exclusion areas, and respecting the special circumstances of the four spaces. Kirkegaard doesn't add anything – instead, he fills the rooms with what is already there. As a cry for us not to forget what happened there, the dense and threatening atmosphere brings the terrifying message of nuclear disaster.

Kirkegaard's intervention is carried out with respect for, and sense of, the space. His recordings bring the abandoned places to life, stretching the barely audible sounds of the four spaces.

Photographic work BLOKU by Jacob Kirkegaard, which portraying the four abandoned rooms which were subject of artist’s recordings during his visit into the Zone of Exclusion, Chernobyl Ukraine in 2005 (sonic project 4 ROOMS is currently shown at MoMA, New York)

Bats and "blind" field recordings

MOMA presents yet another Scandinavian artist: Jana Winderen (Norwegian, b. 1965). Before Winderen got her master's in Fine Arts from Goldsmiths, University of London, she studied mathematics, chemistry, and fish ecology in Oslo. Using sensitive microphones to collect sounds that are unfamiliar and sometimes inaudible to the human ear, she captures sounds from remote locations – deep beneath the ocean’s surface, or in a crevasse in an underwater glacier. Revealing the complexity and strangeness of the natural world is central to her practice. Who knew that cod and shrimp use sound to communicate and select a mate, or that ants at work make a tremendous racket?

For the MOMA exhibition, Winderen has been recording the sounds of bats in flight. In “Ultrafield”, listeners hear even more sounds than the artist did at the time when she was circled by bats flying among a stand of trees. Imperceptible to her at the time, the bats’ ultrasonic echolocation calls have been rendered audible by slowing the recording to one-tenth of its normal speed. These clicking sounds have been combined in “Ultrafield”, along with the chirping stridulations of underwater insects and sounds made by fish to protect their habitats, or to find a mate. The result is a composition echoing the activity of a fragile ecosystem as revealed through sound.

Jana Winderen (Norwegian, b. 1965): Ultrafield 2013. 16-channel ambisonic sound installation. Photo: Mie Dinesen

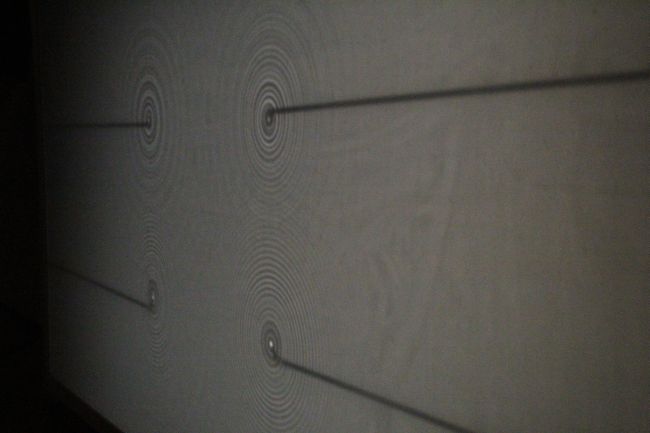

Carsten Nicolai is a visual artist, musician, architect and, most famously, the author of “Grid Index”, a seminal work on the mathematics of grids and visual patterns.

In 2000 he investigated the relationship between order and disorder in milk by pulsing barely audible sound waves into a small pool of milk, thereby generating undulating patterns on the milk’s surface and testing and revealing the elegance of the complex systems.

In Wellenwanne Ifo, Nicolai has created an inventive kinetic sculpture. Using a tank-like container, he directs low-frequency sound waves onto the surface of a pool of water and, with mirrors, projects the patterns the waves create onto a display screen. The patterns change depending on the sound frequencies that produce them, serving as a scientific visualization of the properties of sound and as a meditation on the principles of order and chaos.

Carsten Nicolai, German, born 1965: Wellenwanne lfo, 2012. Water tank, water, mirror, audio equipment, stroboscope, display screen. Photo: Mie Dinesen

Camille Norment's work consists of an old-fashioned standing microphone once regularly used by jazz, blues and pop singers like Elvis Presley and Billie Holiday. Normant removed the interior mechanism and replaced it with a pulsating light that inharmoniously flickers and brightens as if responding to a singer’s breath and voice, invoking the shades and voices of celebrated performers of the past.

Camille Norment, American, born 1970: Triplight, 2008. Microphone cage and stand, light, electronics. Photo: Mie Dinesen

Listening as a collective and social experience

At a time when personal listening devices and tailored play lists have become ever-present, shared aural spaces are increasingly rare. Many of the artists in the exhibition create sound that is social, connecting the visitors in time and space. Many of the works exhibited are designed in a way that makes the way we listen determine what we hear. Indeed, the works provoke and evoke modes of active listening, aiming for re-connecting sound to its reality, context and environment.

What really works in "Soundings: A Contemporary Score" is that the exhibition investigates sounds in relation to the human body and existence. Even though a lot of the installations are very high tech, screens, cables, and computers don't dominate the exhibition. Instead, we find analogue and "old fashioned" equipment and well known artifacts like turntables, microphones, and even oil paintings. Barbara London consciously resists the stereotyped sound art experience of darkened galleries, left bare save for high-end speaker systems and comfortable seating. In stead, the exhibition fits with MoMA’s larger institutional mandate to promote the museum as a social space.

“We hope the show makes you think about how sound impacts your life,” says curator Barbara London. “We all walk around New York with our ear buds in our smart phones and tablets, creating this soundtrack for our lives. In that same way, artists are creating audio environments that are carefully tweaked so we can experience them together.”

However, the social aspect of listening—claimed by the curator to be the focal point of the exhibition—is problematic because many of the installations require concentration and contemplation. With more than a thousand visitors a day, it's rare to locate the necessary silence to listen at MoMA. Tourists, school classes, talkative old ladies and families with kids or screaming babies, along with the instant air conditioning, create a lot of noise, making it difficult to let yourself become engulfed by the sounds around you. “Ultrafield”, by Jane Winderen, might have been more compelling if the sounds of the natural world had remained inaudible. That's one of the reasons Jacob Kirkegaard's installation "Aoin", which is separated from the rest of the sound works by black walls, works so well. The dark room helps us concentrate and allows us to sit down and contemplate for a while.

Installation view of the exhibition Soundings: A Contemporary Score. August 10–November 3, 2013. © 2013 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph: Jonathan Muzikar

Concept and sound as equal components

There seems to be a close correspondence between conceptualism and sound art. Many of the works presented are based on a strong concept or idea that is revealed to us in the text material complimenting the art works. Explaining texts are almost always an issue in exhibitions of contemporary art, and in "Sounding - a Contemporary Score", the art works often demand careful readings to complete the experience and gain understanding. The art works that work the best are the ones that balance the conceptual and the perceptual components. In other words – the sound has to be just as interesting as the underlying concept. A strong concept doesn't necessarily create an interesting aesthetic experience.

The diversity of the artworks in the exhibition reflects a complex and nuanced field. Traditionally, the United States has been left behind the rather strong tradition for sound art in Europe, but "Soundings: A Contemporary Score" takes the first step in prioritizing sound as the important artistic medium it is. Even though it has been three decades since the emergence of the term “sound art,” the genre is still in the process of gaining a persistent presence in the New York art world, from which, I believe, we can expect much more.

Sounds have the ability to transport us and connect us to a time or place. When sounds are de-contextualized and placed in the museum, we experience the ways in which sound can shape our physical, collective, and social experiences in new ways.

Addressing the materiality of sound and examining the auditory aspects of our lives that we take for granted, "Sounding - a Contemporary Score" helps the insisting and attentive visitor understand the framework of our environments. “We live in a really fast-paced world, surrounded by so much sound,” Barbara London says. “We want to encourage our audience to slow down, think and listen.”

*AION is Ancient Greek and means “infinity” or “eternity” - a time span beyond human understanding.