Body in Movement

Alida Ivanov

14/05/2013

Chris Burden

Magasin 3, Stockholm

Until June 2, 2013

Since last September, and for another month, Magasin 3 is showing works by Chris Burden in an exhibition based on technological solutions for moving the human body through space. The show consists of one room that presents “B-Car”, “Mexican Bridge”, collages and notes/drawings. Nostalgia thrives: these pieces have not been together since his solo show at the institution in 1999.

Chris Burden. Installation view at Magasin 3, 2012

Photo: Christian Saltas

Chris Burden was born in 1946 in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1965 he moved to California and got his B.F.A from Pomona College in 1969. Burden went on to obtain a M.F.A from the University of California in 1971. In the early seventies, his work was characterized by an idea that, in the future, what we would see as important and viable art would not be found in objects, e.g., things that you can sell and then hang on your wall. Instead, art would become something ephemeral, and it would be significant politically, socially and technically. Burden’s performances during this time can be described as having a “here and now” –mentality. With their unpretentious yet haunting language, they took this type of art to its extreme, which shook the conventional art world. Paradoxically, now he only makes objects. But in some ways, he’s still trying to obtain the political, social and technological ideal in these as well.

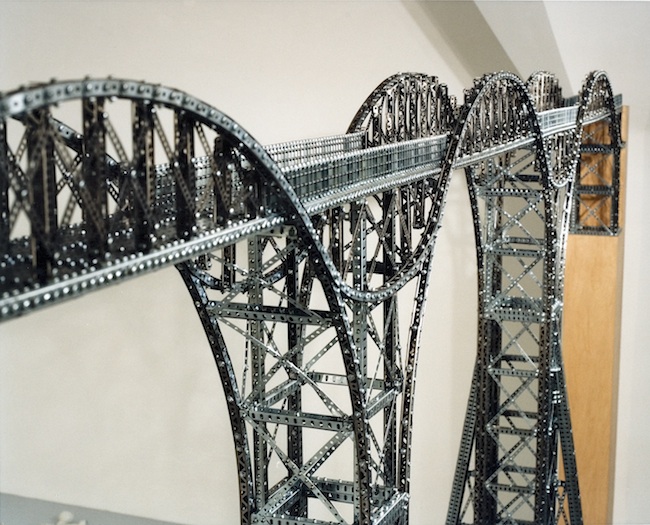

Two out of the four bridges in the “Mexican Bridge” series are shown with “B-Car” (1975) – a handmade single-seated car. The bridges are made out of toy metal construction parts and are based on a never-realized bridge designed in the 1860s – a model for the Mexican railroad system that would have spanned over the 350 m-wide Metlac Gorge. Chris Burden found a drawing of the bridge in a book about the Mexican railroad and decided to build a large-scale model of it with toy construction parts. In the exhibition there are also drawings, photographs and texts that document the projects and reveal Burden’s vision of how a car should be – that same vision that “B-Car” is rooted in.

Like a breeze of fresh air, Magasin 3 contributed to the second season of this show with its newest collection acquisition: “Ode to Santos-Dumont, A Work in Progress” (2013). The piece is a collage, and a part of Chris Burden’s latest project. It is based on the Brazilian aviation pioneer Alberto Santos-Dumont (1873 – 1932), who experimented with designing aircraft during his years in France at the turn of the last century. In 1901, he won the Deutsch Prize for successfully circling the newly-built Eiffel Tower. The collage works as a continuation of Burden’s exploration of movement through space.

But how interesting is this? And what are we actually seeing in this show?

The exhibition is almost like a little boy’s room, with toy cars and models, but in a strange and almost clinical way: the themes are there, but the mess isn’t, so to speak. When you start looking at the details, at the individual pieces, you realize that Chris Burden never stopped using his body as a means for his art. All of a sudden, the question of performance enters: What is it? and How did this performance develop?

Chris Burden. Mexican Bridge, 1988-9 (detail). 800 Meccano and Erector Set parts: 284 x 94 x 477 cm

Photo: Neil Goldstein

In Magasin 3 Artpod, a podcast series with a discussion panel, Chris Burden mentions that in an art performance the artist plays him/herself, while in theater, the actor plays someone else. This is, of course, a simplification that is not really based on how performance art looks like at all. Performance, like art, can be anything, but it is dependent on the setting and who the author is. What I find interesting is the tradition of performance art that Burden is a part of – body art, two examples being “Shoot”, done in 1971, in which Burden let a male colleague shoot him in the arm; and “Trans-Fixed”, performed in 1974, in which he ordered yet another male colleague to nail his hands on the roof of a Volkswagen, which then drove full speed for two minutes. This type of sadomasochistic, fetishizing, corporal performance and, sometimes, dangerous performance is a part of what Burden represents. He makes it clear in the same podcast that he quit performance art mostly because of the aftermath, and the impact his work had in media: if someone shot their friend, there would be a reference to his art. He couldn’t deal with that kind of responsibility, because it shouldn’t be his.

Body art has its roots in the late 60’s- early 70’s, and is in many ways associated with the political climate of that time: the Vietnam-war, emancipation, feminism, and so on. As a form of performance art, it is not that common anymore; you don’t often see people hurting themselves for art. Of course, it’s not the violence that is interesting in body art, but rather the relationship to the body; the female and the male. In Amelia Jones’ “Body Art- Performing the Subject” (1998), she also connects this specific type of sadomasochistic art form that Burden represents to a male code, based on what she calls the Pollockian performative – the genius male artist “painting a picture”, “making a sculpture”, or “creating a world”, the way Jackson Pollock performed the act of painting, and thus presented art as a performance. Chris Burden and many of his contemporaries, like Vito Acconci or Rudolf Schwarzkogler, were, in many ways, exploring masculinity through sadomasochistic behavior and the punctured, suffering body. Burden, of course, displays paradoxical behavior: he is always in charge; he’s the one giving orders and framing his own submission. An act that is actually quite common in the type of sexual relationship in which the submissive agent is actually the one who is in charge. It becomes a power-play between subject and object, between mind and body.

Chris Burden in his studio (February 2013)

To look closer at this power-play, one has to understand the connections even further. In “The Return of Real” (1996), Hal Foster discusses the development of art and theory since 1960. By adapting Sigmund Freud’s notion of "deferred action", he reorders the relation between prewar and postwar avant-gardes. He also tries to contradict Peter Bürger's declaration as written in “The Theory of the Avant-Garde” (1984), which is about the failure of the avant-garde. Foster agrees that the pre-war avant-garde failed in what they sought out to do, but argues that future waves could redeem themselves by incorporating historical references and those aspects that had not been comprehended the first time by its predecessors. In a chapter called “The Crux of Minimalism”, he takes that art movement as an example of an avant-garde that has redeemed itself. Minimalism being, more or less, current with body art performances, it grew out of the same political climate as the latter. The two movements had a similar perspective on the body. Foster points out: minimalism announced a new interest in the body, but as a presence of objects. That power-play between subject and object is also one between subject and body. The object and the body are the same. There is a fetishization of objects in minimalism, which is similar to the fetishization of the body in body art.

Even though Chris Burden has stopped making performances, he has not stopped performing, nor doing body art. The performance is translated into the objects: together, the car, the bridges and the notes form corporeality. This exhibition is ultimately not about a body in movement – it’s about his body: Burden’s body, and in extension, the male body.