Write Life

Alida Ivanov from Stockholm

17/04/2013

Munch! — Nietzsche, Thiel and Scandinavia’s greatest artist

Thielska Galleriet, Stockholm

February 9 – May 12, 2013

People are lining up for this one: Munch! Not only to see Edvard Munch and his work, but also to see his relationships to philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and entrepreneur/art collector Ernest Thiel. The star of the show is, of course, the portrait of Nietzsche. But is this really how the show is outlined?

Thielska Galleriet in Stockholm has the largest collection of Edvard Munch (prints) outside of Norway, so in connection with his 150th birthday, the exhibition Munch! — Nietzsche, Thiel and Scandinavia’s greatest artist, features his works: about twenty oil paintings and 95 prints from the period 1880-1910, most of which come from Thielska Galleriet’s own collection.

The concept around the exhibition Munch! is built around the portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche that was made posthumously and was commissioned in 1905 by Ernest Thiel, a banker, businessman and patron of the arts. He built the gallery/museum as his private home and for his collection of Scandinavian and international art. Also, he was an admirer of Nietzsche and considered Munch to be the artistic equivalent to his spirit and ideas.

Now Thielska Galleriet is finally in a state of gradual change. Andreas Brändström, former gallerist and temporary head of Thielska Galleriet, has made it his task to renew the way the institution works with their collection, the way it thinks around the pieces, and trying to come up with ways to correlate it to the present. This is a tough task because the gallery is full of different rules around what to do and not to do with its collection and house. After a period of scandal (which was mostly led by the former head, who did not want to move out of the house after his pension), it was time for a new beginning. Brändström has taken a stand and has made Thielska “the talk of the town”. Last year the gallery hosted shows with Swedish artists Meta Isæus-Berlin, Sofie Tottie, and Cecilia Ömalm Krajcikova, among others. The last show was Araki/Zorn, in which works by Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki were placed side by side with those of the Swedish turn-of-the-century artist Anders Zorn. This was probably the most obvious attempt to connect the collection to the contemporary.

Munch! is more subtle than that. The contemporary feel is behind the scenes of this show. For one: this is the first show for which Thielska had to lend out work to other institutions in order to borrow themselves, which has never happened before because of the bylaws of the institution. The other thing is the hanging of the pieces: for Munch!, they decided to re-hang the permanent collection, which also goes against the bylaws. This is a part of the forward-thinking agenda. What was the result, then?

Edvard Munch. Madonna. 1902.

Did this create a forward-thinking and contemporary show?

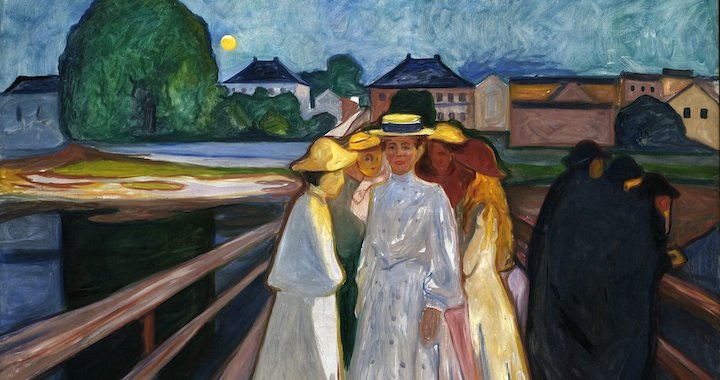

Okay, so the entire exhibition is arranged in three rooms: two rooms holding prints, and one with paintings. In the collection you can see Despair (1892, which is the first version of The Scream, which was painted the following year, in 1893), On the Bridge (1903) and The Sick Child (1907). The 95 prints (of which there were originally 99) are hung in a salon style, which gives out a suffocating type of sensation. It works with the psychological motifs of sexuality, anxiety, and depression. But, this is the obvious way of arranging it; how would you get a feeling out without overbearing the visitor? There is a reason why people stopped hanging work in the salon style.

When entering the painting-section, you go through security – frisked and searched. It adds a bit of excitement. That feeling kind of ends when entering the room, unfortunately. The first thing that you see in the room is the portrait of Nietzsche, but as a whole, it hangs in the periphery of the room. This makes no sense because it is supposed to be the star of the show. The other portrait is placed in another corner, and the death-mask in a third: no one puts Nietzsche in a corner! Except Thielska, apparently.

In this room, they did the “unthinkable” re-hanging of the collection’s 12 paintings; they switched places and combined them with the borrowed paintings. I would like to remember that the portrait of Nietzsche used to have the main place, in the front of the room, which would be perfect for the theme of this show. Just because you are allowed to do something doesn't meant that there is a good enough reason to actually do it. In this case, re-hanging was probably unnecessary. Something that wasn’t taken out of the room is a small sculpture, by Auguste Rodin, in the middle of the room. This adds to the confusion and digresses from the curatorial ambition.

Edvard Munch. På bron / On Bridge. 1903

Edvard Munch had a will to write down his life, so to speak. In this exhibition, Thielska Galleriet captures something. Confusion is a part of life. I would like to see more of how Munch’s art is important to us today. Why does it still affect us? How did he develop with age, if he did? How did he inspire other artists?

You can see that there is a process in the making, that Thielska Galleriet is trying to renew itself, and it’s interesting to see how they re-interpret their collection and interlink it to the present. I, for one, am looking forward to the next show.