A topsy-turvy world

Interview with German photographer Isabelle Wenzel

Sergej Timofejev

23/05/2016

In the Latvian capital, taking its time to embrace spring this year, the 2016 Riga Photography Biennial has been launched. The main exhibition ‘Restart’ (open through 12.06.2016) in the great hall of Riga Art Space features 18 internationally acclaimed photographers who use the medium in a number of different ways, from ‘moving image’ to installation art. In this respect, the works of the Netherlands-based German photographer Isabelle Wenzel could be described as quite traditional: medium-size prints of colour photographs. And yet at the same time everything is topsy-turvy in these pictures: the main subjects of Wenzel’s photo series are literally her legs and body, while the head plays an entirely supporting role, staying somewhere in the background – away from our eyes. A completely different kind of life, led by Isabelle’s body, unfolds in front of our eyes: the body is somewhat awkwardly yet absolutely sincerely hurrying somewhere, falling from somewhere, striking poses and expressing various moods. Sometimes it even loses its humaneness and becomes a stand for various objects. Be that as it may, these photographs, breaking the laws of gravity and telling a story of body-thinking, a story of creating absolutely wonderful if somewhat awkward sculptures out of a single yet variously dressed female body, a story full of vitality and extraordinary adventures, attract attention and raise questions, some of which we decided to ask.

Isabelle Wenzel, who won the Leica Prize back in 2007, is now in her thirties. She is still actively showing in Germany, the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe and publishing her photographs in books. She was visiting Riga for a couple of days only, and we met at the small and quiet office of the Latvian Orbita text group in Ģetrūdes Street. She is a medium-height woman sporting a short haircut; she speaks very calmly and with pleasure, keen to get to the bottom of things. As a child, Isabelle attended an acrobatic studio, and it is quite possible that, had life taken a different turn, we would be watching her perform tricks in the circus ring. In reality, however, the circus has simultaneously shrunk to the boundaries of her photographic studio and expanded to the level of universal questions of human existence. So how did that happen?

Isabelle, there is some sort of displacement, a surreal quality to your pictures – and, at the same time, a clarity and exactness of expression, which makes it possible for their meaning to be quite multi-layered and complex. You work with very specific subjects that have to do with the body and, as far as I know, you first started to take an interest in the body as a means of expression as a child, when you were attending an acrobatic studio?

I was always a very sporty type of girl. And as a child, I simply craved for physical activity, be it a game of football or acrobatics. A shift towards the visual arts and photography was not a conscious decision. The whole thing happened almost as an accident: at the age of 21, I underwent a knee surgery; sports and any physical exercise were temporarily out of the question. And that is why I took up photography. After all, there is no need for a photographer to run around a lot while they are working at a studio; street photography, of course, is a different matter altogether.

And so I just happened to take up photography by accident and went on to study the medium quite purposefully – first back in Germany, then at the Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. And that is when all my ideas about movement, about the focusing of the body started to come back to me – the idea that we articulate a lot through our body in our everyday life.

Initially I photographed other people, my friends, because I hate taking pictures of strangers. I don’t like the power game that is so frequently part of this type of photo sessions. You are trying to get what you want from your model, while they have their own expectations of what they hope to see in the end result. However, what I wanted did not in the slightest coincide with their wishes, and I always felt that I was somehow letting this person down. And I have also never liked this position of projecting my ideas on someone else.

And so, step by step, I started photographing myself increasingly often. At first I had certain doubts about that as well, because I was not sure if that was not actually a narcissistic act – putting myself in the spotlight. But then I understood that this was not actually about me as a person when I was photographing myself. I am simply using my own body to articulate the ideas that visit me. And I gradually worked out this mechanism of interaction with my camera where I push the self-timer button and rush to take my position in front of the lens – and then I run back to take a look at the result. Of course, things get out of control this way, because you are not looking through the lens at the actual moment of taking the picture. I try to ‘formulate’ the image through my body. Today, after many years of doing this, I have finally started to understand better the way that the body works in front of the lens.

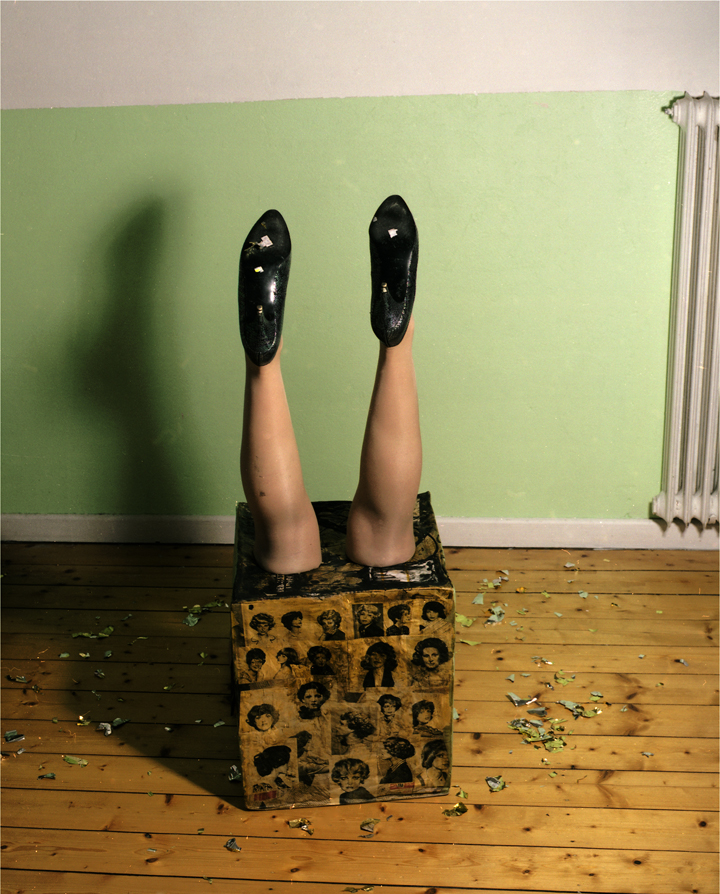

Figure#5. 2011

Which means – the way that this picture can come out?

Yes, the body itself tries to articulate the image. These days, when I photograph, I practically don’t look at the result; it is enough to check it very quickly, and then I carry on doing things again. What I find interesting is a certain unconsciousness of this process – being able not to ask myself what it is that I’m actually doing. I try to release myself from all rational thoughts and think with my body. The brain switches on back again when you have to select the pictures and make decisions on the presentation. But when I’m in front of the camera, I forget about these things. It is like… ‘Action!’

Your head or your face is almost never in your pictures. That is also a certain way of moving away from a specific person...

If there is a face, it is immediately connected with a specific person in the viewer’s mind – or a specific ‘type’ of people. And that was a problem for me. On the one hand, I was trying to conceal in these pictures my own identity; on the other, I wanted to show that the human body is something more than that – something that anyone can project themselves on. Of course, I am a woman, I have a female body, and that is already a typification of sorts – there is no escaping that.

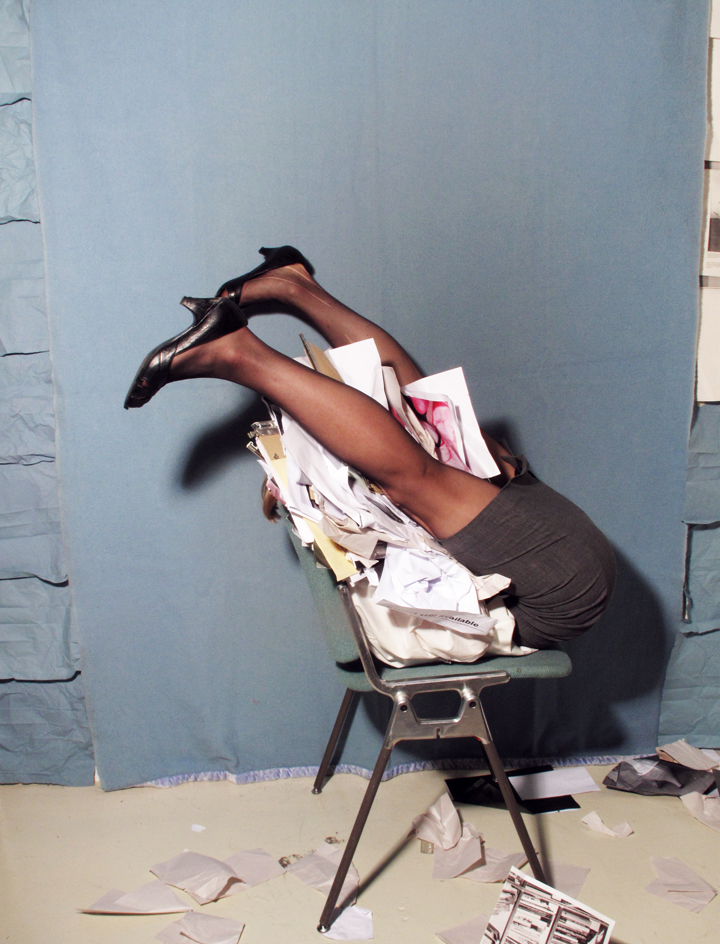

Paper_1_A. 2010

However, the body in these pictures is also dressed in a number of very different ways. There is a very accurate imitation of certain styles and the ways in which we perceive them – the ways in which we show or hide our body in social situations.

I do these things in pictures because I am curious about how they work and I don’t necessarily understand these mechanisms completely. Especially regarding the female body and the ways in which it is labelled in the media or in our collective consciousness – how a woman is supposed to look or behave. As a child, I did not quite get it – and I can’t say that I do completely now.

I was recently actually asking myself why I do use these clothes and all of these sexual connotations – these high heels and these blouses. And I realized that, when I was putting together some sort of model of human appearance as a child, this model for me was a cowboy – smeared with dirt, somewhat wild and living according to his own rules. And I was also quite a wild child, a tomboy. My parents were okay with that: so you’re not behaving like an ordinary girl, but that’s fine. And then at some point I was starting to find this pubertal shift in the way people around me perceived me and my body annoying. Before that, in my childhood, I was often noticed for being so sporty. Something like ‘Yay! She can do all those things!’ And now I suddenly realized that I can be viewed in a different way, with desire, with a sexual subtext. And I understood that there is a difference between the ways in which the movements of a male and a female body are perceived. Although this concept of femininity has never worked for me at all.

And in this sense, there are no strictly defined roles in the relationship between me and my husband. We are equal in our rights and our worth.

Model #5. 2011

But you fell in love with a man...

Yes, and that was also sort of not quite according to the rules, because, when I was younger, I was often told: surely you must be gay. But the fact that you are not behaving in accordance with everyone else’s idea of a young girl’s behaviour does not necessarily mean that you are this or that. I have no need for these ironclad boundaries.

But when you fell in love with your man, you, too, started to view him differently, look at him with different eyes, with a different kind of desire...

Yes... But that is a personal thing, it’s private...

And not as automatic?

Yes. Private looks can be very intimate. What I am referring to is rather the things that take place in public, in the street or elsewhere – with completely unfamiliar people.

Back to the photographs and the types of clothes that you choose for them... It almost seems as if you are giving your body a bit of freedom, a certain opportunity to indulge in some ‘extracurricular activities’ – to be someone else for a while...

I love experimenting with stereotypes. And that is what I want and can show to other people. I would never post my personal pictures on Facebook, for instance. On the other hand, this whole virtual social life thing fascinates me in a way. So many people present imaginary images of themselves to the world – their ideal alter egos. The camera captures a fragment of their existence, and it looks so real. But either we don’t get to see the whole picture, or it is an artificially created situation.

And the actual situation of taking a selfie – how artificial is that? I was at this canteen once where there was a group of young people, five or so guys and girls. They were all sitting with their smartphones and their earphones on, browsing and looking at their stuff. There was no communication between them. And then suddenly one of them said: ‘Let’s take a selfie!’ And they all took their earphones off and put on these super happy smiles, as if there was some sort of mega-cool party going on around them. So they took a selfie and, apparently, posted it online immediately – and went back to their smartphones again...

Strips 6.1.1. 2015. Gallerie Bart

It is a sort of private theatre of pretence (to something). On the other hand, I do hope that this first-hand experience of building an image, of the artificiality of the whole thing in their everyday life will help people look in a more critical way at things presented to them by television and other media.

Yes, for me the media world is something absolutely constructed. I was recently asked to take part in a programme, a sort of TV portrait of me. And I spent quite a long time hesitating – should I? Eventually I did agree, only to witness with my own eyes once again the extent to which the whole thing is manufactured. Walk this way, stand over here. It is impossible to be authentic and act natural during this kind of programme. We try to control it but it is impossible. And this idea – that so much around us cannot be controlled – is a subject that is also very important for me. Any situation can transform at any moment.

And this uncontrollability is also important for me in what I do – how I photograph. On the other hand, I have taken countless pictures; they go their own way in the world, and that is also something that I cannot control. They have a life of their own. And there are so many of them that I cannot even show everything together on my website.

This interest in losing control also manifests itself visually in your works. In the pictures showing moments of falling, in the uncomfortable positions...

I think that falling is not necessarily a bad thing. That depends on how you deal with it. In the actual moment of falling you are almost flying for a split second.

Yes, that is true.

Of course, it is a very brief moment. But it is a moment of ultimate freedom.

And also a moment of vantage-point change. In Leo Tolstoy’s ‘War and Peace’, Andrei Bolkonsky is wounded in the Battle of Austerlitz while he is running forward; he falls to the ground and is now watching the battle from a horizontal position – and that is a completely different perspective, a different system of values.

Oh yes, and he stays there for quite some time...

Isabelle Wenzel. Press photo

And what can you say about the sculptural nature of your works? Perhaps you have at some point been inspired by classical sculptures?

I would not say that I recall being inspired by a specific work of art. I am rather inspired by the whole history of culture. Many things started with sculptures. And you could perhaps say that I re-format, re-form my own body into a sculpture and then take pictures of it. But I also am inspired by inanimate objects – by their history, by their aura. My mum told me that she used to visit her grandfather as a child, and there was a very old desk in his house. So she would get on top of the desk, sit down and think about being an old desk – about how it would feel to be one. I must say that I find this kind of reflection very inspiring.

There is a very specific humour to your photographs. But perhaps it is not at all something that you strive to achieve?

I would say that humour is optional for me. I don’t have a key to it. I don’t understand how it works. And nevertheless it is always somewhere nearby. I actually think it is quite flattering when people look at my pictures with a smile – but it is nevertheless not a goal that I set myself. I do not want to do funny things; I’d rather do thoughtful, even serious things.

Buster Keaton comes to mind here and his ways of making everyone laugh while keeping his face completely straight and expressionless. I am not comparing myself to him; I’m only trying to make a point that it is quite possible to be funny while remaining absolutely serious.

And then there are the failures, the bloopers, which are also comical in their own way. Especially in the series where I am balancing all sorts of objects on my body. I don’t want this vase to smash. But it is so difficult – poising on one leg or on one side while balancing things on my body. And sometimes the vase can land right on my head.

And yet these bloopers do not appear in the pictures? You are not showing them in this series?

Not in this series, no. I have made a couple of videos where you can see them, but I haven’t shown them anywhere as yet. Because the important thing here was merging into one with these objects.

In your interviews you emphasise that our body directly influences our mind. We think not only with our heads but also with our bodies.

When I sit in a chair and think about something, the result can be completely different than if I were actively moving at the moment. On the other hand, when you are performing a somersault, you really must not think about how you are doing it, otherwise you will fail. You need to ‘switch off your head’ in this as well. Which leads us to intuition, and I do not consider it a sort of opposite to rationality, because I really do not believe that rationality is a male thing and intuition is necessarily a female thing. That is complete nonsense; we all have all of that inside us. We would never get anywhere without any intuition at all, because we must have this sense of ‘there is something in this’. To me, intuition is a very important thing, especially in my everyday life. Sometimes my reason would say: ‘Just do it!’ but my intuition would interfere: ‘No, not now, not with these people.’ And it is usually right.

But how do you do this thinking with your body at the moment when the picture is taken? How does it really happen?

It is very difficult to translate into language. Because at that moment I am trying not to think verbally, to switch off my mind. It is a bit like yoga that way. The space where the whole thing is happening on any specific occasion is also important – the way your senses interact with the things that surround you. And it is a kind of rest almost, relaxation... even if the actual physical position is not very comfortable. Because when I am unable to relax, the result is no good. You cannot think about the result – about whether it is going to be good. And for this reason, whenever a deadline is somehow involved, I start working without any delay. Otherwise, the closer it comes, the more impossible getting anything done becomes. No, you have to relax, to switch off all the causes and effects and get stuck in. We shall see afterwards if something has come out of it or not.