Silence Does Not Exist

Elīna Sproģe

20/01/2014

Jacob Kirkegaard (1975) is a Danish sound artist who, after graduating from the Academy of Media Arts Cologne, is now based in Berlin.

Driven by curiosity and his well-trained senses, Kirkegaard creates exquisite audio compositions that he sources from significant processes in the environment. He records his material around the world, from glaciers in Greenland and tribal rituals in Ethiopia, to rocky ravines in the Alps and abandoned industrial sites like the television tower in Berlin and the basements of the Carlsberg brewery in Copenhagen. In doing this, Jacob brings to the forefront the need to listen and to allow sound to come to life, thereby discovering unbounded expanses that we usually exclude from the busy schedules and computer screens of our hectic daily lives. In their own way, his fragile soundscapes absorb the essence of a place and create an illusory space that acts like a memory of the place in question, be it an abandoned church in Chernobyl, or the labyrinths of the inner ear canal.

Music has had a very important place in your life since early childhood, and you can freely play several instruments. How did you arrive at creating sound compositions?

I began to consciously record the surrounding environment in 1995. At the time, there really wasn't anybody in Copenhagen who talked about “sound art”. I was lucky enough to accidentally hear a radio program on musique concrète and the genre's pioneer, Pierre Schaeffer [a French composer and theoretician (1910-1995) – E. S.] It clicked with me, like some humongous revelation that made me realize that the noises of the surrounding environment could be used and, following your own preferences, be arranged into compositions.

I already played the guitar and was learning the cello at the time, but no matter which pieces I played, they all sounded alike. A guitar will always be a guitar. Every instrument has its own historical baggage and, in my opinion, it's hard to shake free from that. I am in awe of people who can play a certain instrument with virtuosity, but I was more excited about the sounds around me.

After listening to this radio program, I understood that that was what I had been doing, and that I wanted to continue doing it. I'd been recording since I was six years old, with a reel-to-reel tape recorder that my father had given me. I took it to school and recorded my friends, but only when I was twenty years old did I see it as having future prospects, and understood that it was a passion of mine.

What was the very first thing that you recorded after coming to this realization?

I caught a wasp and trapped it in a glass. I put a microphone inside of the glass and put on earphones. It sounded as if the wasp was inside my head! I think that was the first recording I did. I had just gotten this small microphone... Yes; I hadn't thought about that for a long time. I also recorded water, but that was later on.

What was it that brought you to the realization that there was an audience for what it is that you do?

This question leads me to think about an earlier period in my life. I think I've always had this urge to communicate with the public. I did start out in the music scene, and I've performed live. I come from punk rock. You know – the hair, playing the guitar... at the time, punk rock seemed like a great way to do things my own way. To stand for something, to refuse to play nice pop songs just to be liked by all the girls. Where I grew up, maybe one or two girls liked what we were doing. Of course, it would have been nice if more had liked it, but somehow, our music didn't speak to them (laughs). Then we thought: to hell with whether or not anyone likes it – let's make some noise!

It doesn't matter which one you do – punk rock or sound art – you're not going to have a huge audience. You know you're not going to be mainstream. My friend Gry Bagøien and I created the group ÆTER [an electronic music collaborative that was active from 1995 to 2001 – E. S.], and we began performing at concerts in Copenhagen. She wrote and sang the songs, while I created the audio background using sounds from my recordings. We became a rather well-known “underground” group and had our own following. I felt a contact with the listener, and I liked that, but it didn't take long for me to understand that it was draining my energy. Consequently, I tried to distance myself in some unconscious way, because I believed that I wasn't creating for an audience. Only later did I realize that, if it's interesting to me, and if it might also mean something to a listener, then that's wonderful!

How did you decide to study art in Cologne?

It wasn't possible to get that sort of an education in Denmark at the time. There were only two options: the art academy – where one was taught traditional art, and the music conservatory – which offered courses in rhythmic or classical music. I didn't subscribe to either of these categories.

We had gone on a concert tour as the warm-up group, together with some people from the German group Einstürzende Neubauten. They're an industrial music group, and play with various metal objects.

We had come to Cologne, and some professors from the Academy of Media Arts came to our concert. Afterwards, they invited us to stay at the Academy, and so we stayed there for about a week. They generously gave us a fully-equipped studio and encouraged us to enroll. I was ready to take this step – in terms of both personal and creative development. I applied and was accepted!

That's not a story one hears often.

To tell the truth, before I enrolled in 2000, I had never thought I'd want to move to Germany, and no one was yet talking about Berlin back then. I had thought that if I were ever to move somewhere, it would most likely be to some tropical and exotic place.

But I ended up in Germany, and with Berlin's growing popularity among young artists, I headed there after finishing my studies. I haven't lived in Denmark for over twelve years now.

Read in Archive: Daily Dozen with Danish sound artist Jacob Kirkegaard

In making ambient sound compositions, you listen to the world – in a way, you register its secrets. How do you feel about that?

For me, it's a way to understand the world without limiting myself to just immediate perception. It's important for me to find other, deeper perspectives. Nothing is what it seems like at first. It's the same with people – I see you, but there are infinite layers hidden behind that; I know this without even knowing what they are. The more time we spend together, the more I'll find out about you. It's the same way with sound. I can sink into it and listen, just the same as one can discover what a person is like on the inside. These are not just attempts at understanding sound – and through it, the world – but also attempts at understanding yourself. This is one of my personal driving forces, and I hope that it will also be important to the listener to experience it.

A large part of your work is linked to traveling. What's the difference between the process of getting to know a place and taking its “voice” along with you, compared to working in a specific place in which the piece will make contact with the listener?

I think that the main difference in “removing” a sound from its context is that the sound is now isolated from everything that you saw and felt at its original location.

When recording volcanic vibrations in Iceland, or melting ice in Greenland, you feel that the place enters you – it overcomes you. All of your senses are sharpened. The air is different, the temperature is different, and the landscape is amazing. You are there with your whole body, and that lessens your ability to simply listen. But when you take this sound with you and you then replay it in a sterile environment, you have the opportunity to really hear it. It becomes something completely different. For example, when creating the installation ISFALD, which was recorded in Greenland, but replayed at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark (and where it still resides), I felt that I had to create a theatrical environment by surrounding the already dusky room with a black curtain. What encouraged me to do that were the common beliefs about the Arctic that have been held throughout history. People have imagined it as a mystical place inhabited by strange creatures, or even as the end of the world. So it was obvious for me to present the sounds in darkness.

This reminds me of your work THIRST, which was set up in an empty swimming pool. Along with the sound, there was this atmosphere of an indescribable and foggy environment.

Yes, this piece really spoke to the audience. In truth, I was a bit surprised about that. I had decided to work with stage fog, which I had last used when playing with the punk rock band. It seemed like a cheap trick, but it really worked that time – as the fog filled the empty pool, it created a dense space. Going through this practically opaque substance, and even without getting wet, one had the feeling of sinking. The speakers through which the geyser “spoke” were placed at the level at which the surface of the pool's water should have been. The sounds of hot water and steam breaking to the surface of the earth flowed throughout the space, while at the bottom of the pool, you heard a recording made via a vibration sensor that had been placed within fissures in the ground. As you descended into the pool, you were accompanied by the sounds that can be heard as you go deeper under the surface of the earth. Theoretically, you were in a layer of earth that one cannot go into in real life. It was sound that allowed for this place to exist.

It's interesting to see how your works adapt to their surroundings when they're exhibited in different places – especially your piece LABYRINTHITIS.

In terms of LABYRINTHITIS, it's interesting that it always changes along with the room in which you are, as well as with your exact location within the room. The feeling in your head changes along with this, because as the sounds echo off of the walls, they create different reactions in the listener's ears. It makes the ear respond with sound! The piece is made up of tonalities generated by my ear. In listening to them, vibrations also form in the ears of the listener.

How large of a role in your works have you given to the extra dimensions of photography and video?

As you already mentioned, I travel a lot to discover various sounds, but I could just as well make a trip to just around the corner from here. I'm not a fetishist who must travel as far as possible to catch the most remotest of sounds (laughs).

I do like to travel the world, but the most important thing is to not just understand the sound, but to also understand the place, the culture and/or the environment through the sound. If I choose to use photography or video as a complement to experiencing this sound, then that is only in order to widen the perspective. I'm concerned with making a portrait of sound. Sometimes it seems to me that photography can do that, like when I worked on the piece SABULATION and studied the “singing sands” phenomenon in Oman; I also made several photo series under the title of NAGARAS. Everything depends on the context in which I'm creating the installation. For instance, when I recorded the Chernobyl project 4 ROOMS, it was only the sound of the room – its resonance. I could have chosen whichever room, but I chose to go there in order to pose the question: How can we understand a place that is enveloped by such a secretive aura? I wanted to work with these abandoned rooms that had once been filled with people, but had then been “taken over” by an unimaginable force– all in order to arrive at an explanation for what changes when the sound comes specifically from Chernobyl, a place that has literally been frozen by radiation.

Photo series NAGARAS, 2008. Oman

Narrative definitely plays a large role in your works. While I was listening to PHANTOM BELL, I was thinking about how you had chosen to link the phenomenon of tinnitus [the neuro-physiological affection when the ears ring when no actual sound is present – E. S.] to the place where you made the recording – an abandoned prison in Uruguay, thereby creating this allegory about being imprisoned in your own head.

Fantastic! That was the idea! Tinnitus, which is forced into one's head, leads to this linkage with prison as a condition that surrounds you, and from which you cannot escape. The feeling of being imprisoned becomes a part of you; it is always present. It seemed interesting to me to cover this phenomenon from which it is impossible to free yourself; you can only learn to live with it. Creating a huge backdrop about this association with prison wasn't the primary thing, but they do go together well.

The installation was set up in one of the prison cells. It was darked and I covered the barred window, which was up by the ceiling, with a filter; this created an artificially blue light, and along with it – a feeling of unreality.

Eight tracks featuring artificially-created human tinnitus sounds were played in the cell. I wanted to portray something that doesn't even exist, at least from an objective standpoint. It's not possible to record this sound; it can only be heard by the person whose brain is creating it. It's like an illusion. Hence the title of PHANTOM BELL, because it's not real. Although it's more than real to those who experience it. I have tinnitus myself. It's a completely real sound that lives in my head.

In trying to repeat this phantom, which both exists and doesn't exist at the same time, I asked several people to describe it. How do they imagine it – What is it? Is it a space? Does it have a color? I was really surprised when I heard the vivid descriptions of what it is that lives in them. I used their descriptions to recreate their tinitius sounds objectively.

As you studied what was happening in others' heads, did you, in some way, arrive at your own inner self-study while creating LABYRINTHITIS?

My work is based on what it is that I hear. The same way as any photographer will take pictures of what he sees from angles that seem interesting to him. Having listened to the world for so long, I found out that my ears create sound themselves. It seemed like a paradox – I used to think that ears were meant just for perceiving that which is outside of my head! It's similar to a tape recorder – while recording, it makes a sort of mechanical sound itself. I wanted to hear this sound – hear the organ that senses sound!

Kā tu uzzināji, ka auss rada skaņu?

How did you find out that the ear makes it own sound?

I was told that by professor Anthony Moore, who was my professor in Cologne. He didn't know if it was possible to make a recording of this. but I was sure they would be a way to find out. When I received the invitation from the Medical Museum in Denmark to make a piece about [biological] cells, I decided that the time was right.

Certain sounds can create fluctuations in a person's emotional state – everything from enjoyment to anxiety. You reflect this perfectly in the piece FEAR, in which you fill a bunker tunnel with a high-frequency sound, thereby forcing the listener out of his or her comfort zone. What do you think is the explanation for these different feelings?

Sound is beyond our control. The feelings come over you and you can't do anything. You can't catch the invisible, and you can't run away from it.

If you see a man that you're afraid of, you can cross the street or run away – you can take aim at the object that you fear. But sound – it is everywhere!

For instance, my voice. You are safe in listening to it. You know that I couldn't suddenly emit a noise at some extreme frequency. But if a sound is either so high or so low that it can barely be heard or felt, it engages on a different level of consciousness, and you don't know if it is dangerous or not. Sound affects us in a way that we can't protect ourselves from it. Fear arises!

I just created an installation that is based on the piece FEAR. It's called HYPERACUSIS, which means “the fear of sound”. It can still be seen in the exhibition for which I specifically made it, Dread – fear in the age of technological acceleration – De Hallen Haarlem's young Curators' Grant, in Holland.

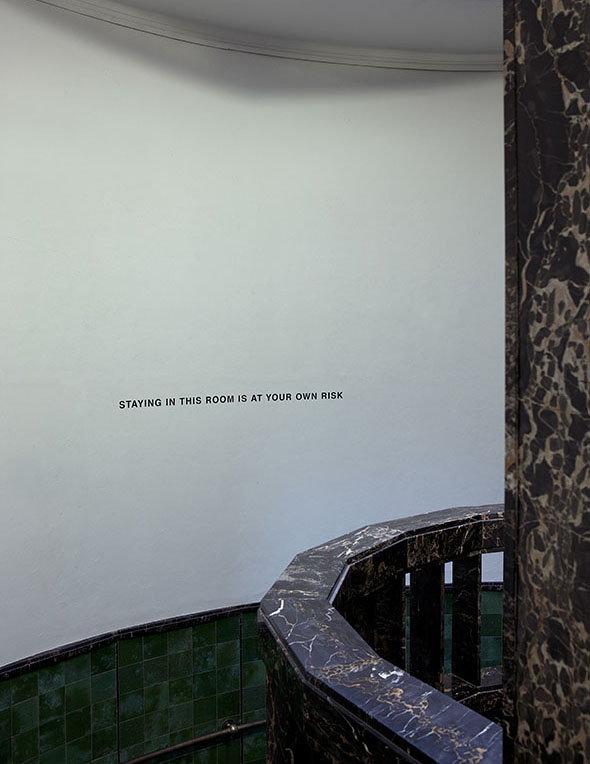

I created a room in which you don't hear anything as you pass through it, but when you come to the end of it, there's a sign on the wall that says “Staying in this room is at your own risk.” Next to the sign is a text that explains that inaudible sounds at ultra-high frequencies are being transmitted at the moment. These frequencies are used in war, which means that after about ten minutes, your cells will begin to break down. You can't hear it, but it's there.

Of course, no sound is being transmitted in the room in this case, but it plays with your subconscious – it makes you scared. Peoples' first reaction could be panic. The person believes that he or she is being exposed to something that cannot be stopped. The fear is irrational – people try to get out of there as quickly as they can. When you are afraid of something concrete, that is fear; but this sort of fear is more like...

Like the German “angst”?

Exactly! That is the most paradoxical thing – that fear can exist even without any rational basis. You are afraid of the fact that you are not controlling the situation.

HYPERACUSIS, 2013. From the exhibition Dread – fear in the age of technological acceleration – De Hallen Haarlem's young Curators' Grant, in Haarlem, Holland

What other interesting comments have you heard from visitors who, even though they are constantly surrounded by industrial noise and music from shopping mall loudspeakers, can still allow your sound compositions to affect them?

The most striking reaction that I can think of was that of a woman who had experienced LABYRINTHITIS in Spain. She sent me an e-mail after the event. We are complete strangers, of course, which is why she felt uncomfortable approaching me while I was still in the venue. Overcome by the waves of sound, she couldn't control her breathing, and she experienced a sexually-charged upwelling of emotion.

That really surprised me – the wide spectrum of feelings that sound can incite. Just like when hearing a sharp and piercing noise, I am overcome with irrational anger.

Yes, even background music that is too loud and doesn't let me focus my thoughts can make me loose my temper!

Yes, that's the way it is, and that's why I feel truly happy when I manage to record a really good sound. When standing on a mountaintop somewhere, and you feel – ah, it's here!

How existential!

Yes – exactly! The same happens when you walk down the street and the things that you perceive around yourself sink down into your memory. That is also good, and perhaps important. But, if you are able to capture this abstract feeling, and you can record it... I really feel existential – as if, just for a moment, I have captured the world. It doesn't just slip by – it becomes mine! I believe that all of us want to feel this. It is extremely inspiring – to be one with the world. To dive into the noise and become part of it.

You know, when you put on earphones, you are simply listening with all of your being.

I spent ten days in Russia, completely on my own; I didn't speak the language. I was in the middle of nowhere, and I had come to capture what Russia sounded like. [For the 2009 performance RUSSIA, NyAveNy, in Copenhagen – E. S.]

You also work with subjects that many associate with paranormal activities, such as recording in a psychiatric hospital (CAPAS MENTALES, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2010), or recording the noises that people make as they are sleeping (HOUSE OF MARE, Hotel Marienbad, Berlin, 2010). Do you believe in, or maybe you've experienced, some sort of unexplainable interference while recording?

I'd like to say I haven't, but I have a feeling that I have. While listening to one of my Chernobyl recordings, I heard footsteps. I thought it must have been an animal, but a camera had been filming the room at the same time, and there was no one to be seen on the video.

No one has ever asked me about this. I don't feel fear, even though I do believe in unexplainable phenomena. I totally respect these powerful energies. It's the same with darkness – if you look really closely at it, allow it to envelop you, you see that it is truly fascinating.

The Chernobyl project 4 ROOMS showed how “alive” an abandoned place can be. Just like in Iceland, in your piece SPHERE, the unimaginable was discovered – the melody of the Northern Lights. Can you describe what it feels like when you hear a specific place “speaking” to you?

We all know that silence does not exist. There is always sound, so there is always something to record. Everything depends on how we listen, and what sort of equipment and methods we use. In Chernobyl I used the technique of overlapping recordings which were made by playing the initial recording again and again, back into the same room; not only was the sound awoken in this way, but also time – which has been fated to stay frozen there for more than70 thousand years. The feeling was not unlike that of an exorcism – a room that had seemingly been saturated with silence had suddenly regained its life. It was the opportunity to hear that which had always been there, because this resonance (he taps against a water glass) – it is continual; we simply can't hear it. If we now placed a contact-microphone up against this glass, we'd hear my voice with this light undertone, thereby revealing yet another level of the broad spectrum of sound.

In the plane on the flight here, I realized that if I opened my mouth slightly and pushed my jaw forward, I could hear higher frequency sounds. I thought – if we could intensify this a hundred-fold, what would we discover? What sort of indescribable sounds / worlds actually surround us? All we can do is use the meager senses we've been given and try to broaden the horizon.