The Destructive Estonian Romantic

Viestarts Gailītis

12/11/2013

While heading to meet Raoul Kurvitz (1961), I look at on on-line picture of him – a thin and sombre dandy, dressed all in black. I allow my mind to stereotype him as being, in all likely-hood, a reticent snob. Actually, he's quite the opposite – at the cafe I'm met by a temperamental Estonian sitting behind a cup of black coffee, a cigarette hanging from the corner of his mouth and with a penchant for old-fashioned, romantic existentialism (i.e., “...the pain of knowing...”, as he sings in the remix of his outlandish hit, “Darkness, Darkness”). Born in 1961 – and having given a presentation as part of the educational event series “Kompass”, which was held at the Totaldobže art center at the end of last May – the artist Raoul Kurvitz is a modern-day classic master of Estonian art, as well as one of the “fathers” of the local performance art scene. During our conversation, this interdisciplinary art veteran reminisced about his beginnings in performance art (a discipline which, by the way, now has its own department at the Estonian Academy of Arts), shared the dreams of his youth, and revealed why it is that the new architecture in Estonia is better than that in Latvia. The KUMU Museum in Tallinn had a comprehensive retrospective on Raoul Kurvitz from January through April of this year.

Raoul Kurvitz in his youth

Right now [the interview was held at the end of May – V.G.], a lot of people from the art world can be found at the Venice Biennale. I hope you don't regret being in Riga, instead of there.

Not at all. I had the historic opportunity to be in Venice and represent Estonia when it participated for the first time – in 1997. We were three men – Jaan Toomik, Siim-Tanel Annus, and I. A real adventure. We didn't have any kind of pavilion at that time. The Biennial's decision to accept Estonia came so late that the country didn't know who to send; they obviously decided to send “those three performers”, with the hope that they could do something crazy right there – on the street. But the curators of the Biennale wanted us to leave something behind, and we had to go through a lot of trouble to do that, since Estonia hadn't planned that we'd be leaving something – that hadn't been their intent. Consequently, we had to invest something ourselves. It cost me, personally, a quarter of a million Estonian kroon [a little over 11,000 lats – V.G].

Of your own money?

Yes, it was my own money. The Estonian government gave us 3000 kroon [a little over 130 lats – V.G.], then another 3000, but they weren't planning on us building something. It was done on our initiative, and it was our risk to take. It was pretty crazy, but I really enjoyed it – it was one of the greatest adventures of my life!

You said it cost you a quarter of a million – weren't you living in near-starvation after that?

I was deeply in debt for two years. When I paid it off, I was faced with the next challenge – a huge exhibition a the Tallinn Kunstihoone art space, in 1999. It was a huge show in which I presented a third of everything I had created. For the next two years, I was again a quarter of a million in debt! (Laughs) That's how an artists lives, if one wants to work on a large scale. Somehow, I've created the kind of image that everyone expects big things from me. I can no longer work on smaller scales because if I do something small, the public won't be satisfied. But the big things are expensive, and they take up a lot of energy.

Obviously, you believe it's worth it.

I wouldn't change it for anything! It's what I've chosen to do and I love it, even though it is awful. That's my lifestyle.

So, instead of complaining about the hard life of an artist, you take it to the extreme?

Of course, I suffer. But it's worth it, to me.

Excuse me for asking, but taking into account these huge personal expenditures, is it possible to sustain a family with this sort of lifestyle?

No, it's not. I've been married three times, and I have a great kid – he's already grown and does his own things, but the model family simply doesn't work in this case. Of course, one can never say “never”, but I don't harbor any illusions anymore. Art is both my life and my family.

You openly work on a large scale now, but you started out on the underground scene, didn't you? – Since performance art was a marginal form of expression during the soviet era.

Everything was different back then. I was born in 1961, which was a very lucky time because we had the good fortune to start working shortly before perestroika. It wasn't even the time of perestroika yet, but rather, the deepest period of soviet stagnation. I graduated from college in 1984 – as an architect, by the way. But I never wanted to be an architect.

Was the architecture department at the Estonian Academy of Arts?

Yes, and it still is. The fine arts were politicized, and in addition, I didn't want to serve in the army. What was also clear was that, if I wanted to be admitted into the graphic arts department, I wouldn't get in – at least not on the first try – because I wasn't active in the Young Communist League and such things. At the time, it was quite common for young men to apply for a spot to study architecture, or design, or something like that – a subject for which there was less competition – and then switch to the fine arts. But I finished architecture, up to the very end. Immediately after graduating in 1984, I had ambitious plans to form not only a group, but a whole movement that would bring the winds of revolution to Estonia. My comrades and I were real radicals. But of course, we had to work underground. When we entered the art world, we weren't even artists – we were architects. I mostly worked together with my partner, Urmas Muru. We used to look quite similar back then. If you've heard of groups like Bauhaus, you'll know what I mean.

Like Einstürzende Neubauten...?

Precisely. We wore makeup, black suits with white shirts, narrow black neckties, and so on. That was a year before perestroika, and we wanted to test the waters – see what was possible. We were always scared that we would be arrested. (Laughs). We took risks, nothing bad happened, and so we became increasingly more daring. Soon enough, we started acting as demonstrative anarchists, even though we never said outright that our objective was to take down the system. We never came with political messages, but our actions were very political – it was destructive.

And the militsiya never approached you?

Amazingly, no. We waited for them every day, but then perestroika and glasnost started, and it seems that one of its policies was to allow the alternative youth to express itself. That's what I mean when I say that we were lucky enough to have been born at a time when we were able to do what we wanted, and without ending up behind bars.

Could it be possible that law enforcement just didn't understand what you were up to?

Yes; because no one had ever seen performances before then. There was the older generation, which knew of “happenings”, but those were much more aesthetic and non-aggressive performances. We had aggressive campaigns.

For instance?

We didn't even call what we were doing “performances”, but rather, we presented them as dances or concerts. For example, three of us would perform a dance with long knives, sticks and rocks. We'd start slowly, with choreography, but then we'd gradually become ever more wild, and the dance would end by demolishing the room. The music and lighting enhanced the whole thing.

Did you consciously include a political subtext?

A powerful, but unspoken message was woven throughout the performances – Destroy! Everyone knew that we meant destroying the system, and bringing about anarchy. But when the system actually did come tumbling down – when Estonia regained its independence and capitalism rolled in – this form of campaigning immediately lost its point and it could no longer continue.

We were also tired, since performance art wasn't our objective; we only did it as an auxiliary element to our installations, paintings, writings, and so forth. In 1991, we wanted to cut off all ties with doing performances. But that's exactly when we started getting invitations to perform abroad. That surprised me; I didn't like it because performances were not the main thing that I wanted to work on. At the time, I wanted to show my trans-avant garde paintings and installations. But well-known Western museum curators weren't interested in my installations; they wanted performances. They wanted the aggression, the scandal, the breaking of things – the things we couldn't stand anymore. Instead of declining, we decided to get rid of the invitations by demanding increasingly larger fees and becoming ever more cynical. We used these tactics to tell them: People, you don't understand what you want; you want complete self-destruction, the destruction of art, because what we're showing is what it would be like if there were no art at all; we're not doing art – you've misunderstood. We didn't say this outright, but this was what we were signaling with our performative gestures. I think that, at some point, they understood this (chuckles), because the avalanche of invitations stopped around 1993, and I could take a breath of relief.

Reconstruction of Myra F (1989/1991) installation. From exhibition at KUMU. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

Taking into account how influential curators are, what should their role be?

In my opinion, from the mid-90s to the beginning of the 21st century, curators acted horribly – like the kings and gods of the art world. I'm not the only artists who thinks that. But I've noticed that, over the last six or seven years, the situation has settled down. I've met enough curators who really like working together with artists. In the 90's, they just called upon us to fulfill their wishes. It was like a slave market. For instance, there would be an article in the newspaper about a huge exhibition with around 60 artworks, but not a single artist was mentioned, just the curator, who then pontificated on his idea. That was very characteristic of the time.

It's changed now – a curator usually works with one, two or three artists in smaller groups, and it can really be called an interaction between the curator's work and ideas. We have a couple of really good curators in Estonia, too. For example, Kati Ilves, who curated my show at KUMU. She's young, and it was her first big show. She did a really good job; I'm very satisfied.

What was it that you liked about the way she worked?

I liked the fact that her approach was supportive. She helped select the works; we talked a lot because my output is huge – but she knew how to choose the right pieces. I'm not good at doing that. The practical things, too, of course – she helped with the logistics, and she also wrote the accompanying texts for the viewing public. This is where the curator's role is essential, because an artist doesn't have to be able to tell the public what he was thinking. The curator must be the middle-man between the artist and his audience, and she did this wonderfully.

Why do you think the Western curators were so fascinated by this destruction, especially taking into account that they came from a completely different system?

Perhaps they perceived it as a show, and they saw that it worked. Maybe by announcing that an exhibition's opening will be a performance, they cold draw a larger crowd. There's a certain intrigue there; an intellectual intrigue, at that – its own kind of psychological thriller. (Laughs) It's too simplistic for a creative person to watch “The Terminator”, but with our destructive performances, we created a “Terminator”-effect that came with an intellectual alibi.

There's a certain dysfunction there – they wanted something that didn't interest you anymore, but you accepted it because in exchange, you got money and the chance to go abroad. I've heard about a similar situation that happened in Latvia, with both sides having completely different expectations. There was a well-known independent performance artist in Riga, who received a prestigious stipend to go to Berlin; the trip turned out to be a fiasco because the situation was such that he just couldn't fit in. Perhaps you knew him? He was Hardijs Lediņš, and his colleague was Juris Boiko.

Yes, I knew them, but not personally. When we worked with performances in the 1980s, the scene in Berlin at the end of the 1970s was our foremost example; it was our dream to go there and continue with the same movement. We harbored a romantically anarchistic idea about revolution. We planned to bring about a revolution in the East, and then continue with it throughout the world, together with Pink Floyd, the punks, and so on. (Laughs) It was a huge disappointment when I finally got to Berlin and I didn't see any of the things I had heard about. It was the stagnant, decadent West. All I got to do was say hello to the bass guitarist of Einstürzende Neubauten in some bar. I went from gallery to gallery, trying to come into contact with the radical art world, but it ended in frustration because I didn't get to experience any of it!

Later on, I tried to explain it to myself with the fact that the fall of the USSR, and the truths that were revealed along with that, made the Western radicals finally understand that their illusions about the socialistic paradise where just that – illusions, and so they shut up in shame. In any case, it was a real disappointment. I understood how deeply bourgeois the West is, and that it's impossible to fight against it. Having come to terms with the fact that the system cannot be changed, I decided to be a romantic anarchist – in my heart.

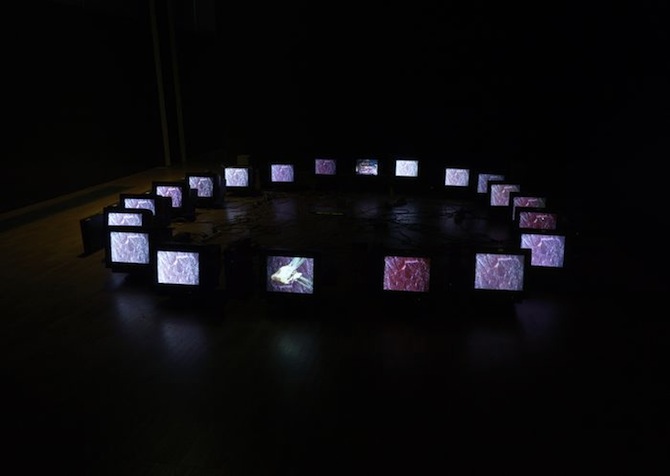

Maelstrom (1999/2013) intallation. From ehibition at KUMU. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

Why do you think that there were similar expressions of performance art in both Estonia and Latvia? Was it the zeitgeist of the times?

The genre, as such, was invented in the 1960s, in the West, and it was often accompanied by a revolutionary spirit – which in the 80s, had jumped over to the East. We already knew about Joseph Beuys and Marina Abramović, but suddenly, the “revolutionary situation” in Eastern Europe was ripe, and it led us to take action. We had the Western precedent as an example, and now it was our turn to do it – our way. We wrote six or seven manifestos. We also thought a lot about things like – How are we different from Joseph Beuys? How are we different from our predecessors? We declared that we were a lot “cooler”. Alright, we were aggressive, but without any pathos. We didn't have any religious messages, or messages of freedom; we were simply “cool”. When I was a teenager in the 70s, I was really into progressive rock – Yes, Genesis, Pink Floyd. Then post-punk came along, which also fit our attitude.

In my opinion, artists and musicians should cooperate more often, since there are more than enough fertile meeting places. A whole slew of experimental musicians have gone to art school.

Already from the very beginning, I wanted to be interdisciplinary. Sometimes I've been confused about what I really am – since I combine installations with sound and video, and if necessary, with performative elements and texts. Namely, I work with the entire environment.

That's a different road than that of artists that work within one discipline. First of all, it seems like it would be much harder to sell your work.

Yes, it is much harder. Who wants to buy an installation?

Is the work of an interdisciplinary artist based on projects?

Yes, exclusively. But I've always loved to paint, so I can sell paintings. But that's also difficult, because I paint works of enormous size; that is radical contemporary painting. Unfortunately, the buying public rarely wants such large paintings on the walls of their homes. Occasionally, a museum will buy an installation. At my last exhibition at KUMU, some of my philosophically conceptual drawings sold.

When you first turned to art, was it clear to you what form of art interested you the most?

As I mentioned before, I wanted to do fine arts, but I didn't look to painting because there weren't any good examples. I imagined myself as a graphic artist, but then I saw trans-avant garde paintings in a catalog and I realized – that's what I want to do! Painting still is the process that I am closest to because it allows me to work by myself. Working on an installation is completely something else – it's linked more with logistics and the ability to organize the work of a team. It's similar to architecture, but even an architect doesn't have to actually build his own plans. It's a set model – to be a contemporary artist that doesn't work alone, but organizes other people, who then bring his ideas to life.

When you first turned to architecture, did you have any interest in architecture at all, instead of just using it as a stepping stone to get to other forms of art?

No, I didn't. Ironically enough, I was a rather successful architect. Urmas Muru and I won a big competition for designing the Tallinn House of Fashion. However, once we finished the project stage, it was clear that it was never going to be built – Moscow had cut off the flow of cash. Moscow said: You want to be free? Then be free! (Laughs) So, the building was never erected, but we were acknowledged, and ever since the day the project was halted and I went home that day after work, I've been an independent artist.

I have often compared the new architecture in both Tallinn and Riga, and barring a few individual examples, the architecture in Riga is tragic – it is aesthetic illiteracy – whereas in Tallinn, the new architecture is relatively good. I think you've partly explained the reason for this phenomenon – in Riga, architecture is taught at the Technical University, whereas in Tallinn, architecture is taught at the Academy of Arts. At the Technical University, the engineering thought process is primary, not artistic instincts.

We've been very proud of this; I think it is good that architects gain their education in an artistic environment – this has a very strong influence on their thinking. I teach conceptual drawing and artistic installation to architecture students, and they really enjoy it and work at it. An architectural degree has given me a very good foundation on which to work with such all-encompassing artworks.

Since you did graduate from the architecture department, you never did follow through with your plan to transfer to a different department.

That's correct, even though I did plan on transferring to the graphic arts. In my first year, I took preparatory courses meant for graphic arts' students. In my second year, I went to see the head of the lithography department; being an older professor, he looked at my work and, with good intentions, said to me: “Yes, you have talent; you just have to work on the details. I'll give you books on ornamentation, and you go to the Old Town and draw some of the street lanterns there.” I was quite radical at the time, and what he had said simply brought out disgust in me. (Chuckles) It was completely against my notions of what art was. I was disappointed, but I didn't have any other constructive ideas, so I simply continued with architecture. Only in my final year did I see trans-avant garde paintings for the first time, and then it was too late to change departments.

If you had to start your academic education from anew, what would you study today?

Today it's completely different; it's incomparable! Young people have absolutely every option open to them. Nevertheless, even though it sounds strange, if I think about it, I'd say I'd study architecture. (Chuckles) And I'd study for longer, since there is no longer the risk of being drafted into the Soviet Army. Maybe I'd study architecture for three years, then take a break for a year, and then study installation; and finally, I'd turn to the fine arts, where painting and lithography are no longer separated one from another. Most likely, I'd also study art abroad – to gain a wider perspective.

Pentatonic Color System II (1994/1999) installation. From exhibition at KUMU. Photo: Stanislav Stepaško

You said that at the beginning of the 90s, the era of performance art had already passed. However, as one system was replaced with another, you probably also saw the idiocy of the market economy that replaced the idiocy of communism. Do you think there's a place for revolutionary impulses in today's art?

Undoubtedly, because there are a great many things that are wrong with capitalism, and it is the job of the artist to point those out and to think of alternative solutions. But I don't think that this has to be done aggressively. The time for aggressive methods has passed, it seems. It seems to be more of a time for collective and alternative thinking. I really liked the New York campaign, in which thousands of people gathered on Wall Street and, by simply quietly standing there, they got their message across. There were results. And, as we know, performance art has returned, and it's becoming increasingly popular. I completely agree that today, performances could possibly be the best way of expressing one's political views on capitalism – just like we did with communism back then.

So, in your opinion, the instinctual affinity you have for romantic anarchy could have a role to play in today's Estonia, Latvia and elsewhere in Eastern Europe?

It's making a comeback. The world has changed, and the masses have understood that capitalism is not humanity's end-all. Even the big-money people have understood that you can't just keep on endlessly printing money that has no real value or basis. I suggest that we start changing the world by having three hundred or so of the richest people in the world come together, and have them cross off nine of the ten zeros that are on the tail-end of the world's existing capital! (Laughs)

In looking at the scale and materials of your artworks, it seems as if there's an industrial art influence in there – something coarse and big and, at the same time, fragile.

Those are the main reference points in my art; I like the contradiction that exists between coarseness and fragility. Possibly unconsciously at first, but later consciously, I developed my own approach – a particular kind of industrial romanticism. Working as an architect, my daily job was to design factories, power stations, laboratories and other industrial structures. The soviet modular systems were very crude and limiting, but we liked doing that. Through experience, I discovered ways in which to transfer this to conceptual art; combining industrial elements with nature; working in survival zones, so to say. In the industrial world, the hippy mentality was something abhorrent – it was against nature. Our attitude was different – that it is nothing more than an evolutionary process in which both sides must be preserved, and in which they must learn to live with one another. To us, the most interesting thing seemed to be the zone where the industrial world meets up with nature: where the dandy – the urban lion – comes to the edge of the city and steps off of the asphalt, and heads into nature.