“You blink, and software-hardware have changed”. An interview with Barbara London

Alida Ivanov

24/10/2013

Barbara London has been the curator of video and media at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York since the 1970’s. She has organized various video and media exhibitions like Looking at Music 3.0 (2011), Looking at Music: Side 2 (2010), Looking at Music (2008), Automatic Update (2007), River of Crime (2006), Stillness: Michael Snow and Sam Taylor-Wood (2005), Anime!! (2005), Music and Media (2004), TimeStream (2001); a series of web projects undertaken in China, Russia, and Japan; Video Spaces: Eight Installations (1995); and Projects exhibitions with Nam June Paik, Shigeko Kubota, Peter Campus, Thierry Kuntzel, Steve McQueen, and Song Dong, to name a few. Most recently, she curated a sound art exhibition at MoMA entitled Soundings: A Contemporary Score, which showed work by Haroon Mirza, Carsten Nicolai, Susan Phillipsz, Christine Sun Kim and Marco Fusinato, among eleven others. She has also written and lectured widely.

London was invited to give a seminar in connection with the public sound art project Augmented Spatiality, in Stockholm. We decided to meet in Gothenburg, but we got caught up in the biennale. Back in Stockholm, I met her when she had just arrived back from Gothenburg, suitcases and impressions in hand.

I got a job at MoMA and worked as an assistant on a painting and sculpture show that went to Australia. It had the work of Lynda Benglis, Richard Serra, Keith Sonnier and Robert Morris – artists who were working with video, as well as sculpture and painting. With the curator, I then helped select an accompanying video program. In the 70’s, many artists had an interdisciplinary practice. I think that an artist like Richard Serra had maybe worked himself into a corner, and video was a way for him to kind of be freer and still work with big ideas with weight. Around the time that the show went to Australia, I moved over to the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, which is where I started the artist book collection and the ongoing video program. I loved it because very little was written, and I was able to work directly with artists, to figure out what they were doing, how they were pushing their vocabulary.

The video exhibition and collection programs began slowly. We had a small “advisory committee” that gave us the means to acquire works. Then I and video moved into the Department of Film. I’m not a film curator. I was working with video.

And how long has MoMA had a Department of Film then?

MoMA was founded in 1929 and the Film Department was founded in 1935. So, MoMA is unusual in that sense. Initial curatorial departments included painting and sculpture, prints and illustrated books, drawings, architecture and design. Photography was added relatively early to the collection and the programming. So, when I began working with video, it was the first medium to be added to the museum since photography and film. Administratively, it made sense for video to be with the other moving image mediums. Artists were experimenting with film, and they were experimenting with video. Installation was a practice, so around 1971, MoMA initiated Projects, an exhibition series that responded quickly to what was going on. Early on, I organized Projects shows with such artists as Nam June Paik, Peter Campus, Joan Jonas and Shigeko Kubota. We had a small video gallery where we showed installations and thematic programs with single channel videos.

I launched Video Viewpoints, a show-and-tell series where artists came and presented their work and talked about it. I always emphasized the discussing along with the showing. At that point, artists were really mostly showing work in very rough, downtown “alternative spaces,” taking advantage of inexpensive rents. Some artists initially were skittish: why should they go into a large institution like MoMA?

Could you tell me a bit about the department that you’re running now?

Initially, video was part of the Film Department. Years later, the Film Department was renamed Film and Video. Then it was renamed Film and Media. Then media was split off from film. The distinction was that film was meant for screening in a theater; video, which was becoming media, was intended for a gallery. MoMA never used the term new media, because that’s an industry term. Today, our department is called Media and Performance Art. Once film and media were separated five years ago, I’ve been in that department. For years I’ve organized exhibition of video, media, installation, and have helped shape the media collection. I’ve worked with many curatorial colleagues, including Klaus Biesenbach, Sabine Breitwieser, and now Stuart Comer is just coming in.

There seems to be a good flow.

It is good to have different points of view, and the ideas of a younger curatorial generation. I think our current director (Glenn D. Lowry) is very interested in internal curatorial conversations that move across curatorial departments.

In this seminar that you held here in Stockholm for Augmented Spatiality, you talked about the exhibition Soundings: A Contemporary Score at MoMA. How do you integrate all of these art forms into the program – like sound art, media art or digital art?

It also depends on who the artist is and what their work is. The museum acquired the work of Feng Mengbo, a Beijing-based artist who for years has riffed on video games. This particular recent acquisition is Long March Re-Start. It was just presented at MoMAPS1.

My colleague Paola Antonelli is in the Department of Architecture and Design, and she looks at media in terms of design. She and I talk a lot about artists’ point of view and how they use tools. Our director encourages contemporary curators to think more in terms of the artist’s practice, and less about the department we are in. We can focus more on artists’ ideas and what’s happening in society.

Institutionally, we have come a long way with media. In the very beginning, I had to learn how to fix things if an installation broke down. Now we have a great team—three media conservators and an eight-person team of technicians. Before we acquire an installation, we evaluate what our obligation will be technically, and we carefully review what the particular artist’s vision and aesthetics are. We need to consider what will happen when the curator and the artist are no longer around. How will we handle upgrades and make sure the vision continues. We try to assemble as much information as possible. If, in the future, we need to upgrade, what constitutes the work: projection size, scale of the room, the sound level or the sound texture, the dimensions. In a museum, we have conservators who deal with painting, with sculpture, with photography; so now, we actually have three conservators who deal solely with media. MoMA’s collection includes media in many different departments: Architecture and Design, Painting and Sculpture, Photography, and Media and Performance Art. We have an AV-crew who are trained in software and understand audio. As I was organizing my “Soundings” exhibition for over a year and a half, I met every week with this team of a/v specialists and exhibition designers, so we talked through all aspects of the technical and the aesthetics. And there are sixteen artists!

Technology is something that changes so fast.

You blink, and software/hardware have changed.

And then you have to back-up. Where does that boundary go – between backing-up and copying something?

The definitions are precise. If an institution or a private collector acquires an unlimited edition, single-channel work of video, they sign a contract. Early on, the contract with an artist allowed the Museum to have up to three copies at any one time. One would be the archival copy and kept under climate-controlled conditions, the second would be the exhibition copy, and the third one would be the study copy. If a scholar came in to do research in the Video Study Center and wanted to look at a particular single channel video, they would look at the study copy.

Now, everything has changed because the world has gone digital. In terms of single-channel video, work is now acquired in a digital, not an analog, format – as in the old days. We’ve gone back to the earliest analog, single-channel, unlimited edition videos acquired in the 1970s, and working closely with the artists and/or their distributors, we have obtained digital versions of these early works. Now the “masters” are stored digitally. The “ownership” agreement is still a contract, and of course, we won’t make multiple copies. We have the rights to show these single-channel videos only on the Museum’s premises. We no longer use DVDs as an exhibition format.

I’ve been thinking a lot about video art. Many video artists today stream their work on Youtube and Vimeo. I remember when I worked at a gallery in 2005, we would have a DVD-disc in a few editions, and that was what you sold. It’s not like that anymore.

Youtube and Vimeo are used by artists to get information out about their work. DVDs are low-grade exhibition format. Because the images on DVD are compressed, they have artifacts and are of mediocre quality.

Moreover, within several years, a DVD will bubble and warp. The artist’s archival master should be maintained in a more stable and higher resolution format. If a collector ever acquired an artist’s video in DVD format in the past, then at the same time, they should have received a contract that would have indicated that “this work is in an edition of five, with one AP.” Now, the collector should go back to the dealer or artist and ask to receive a more stable archival format.

Many video artists of my generation show their work online nowadays…

Back in the very early days of video in the U.S., artists might have shown their work on public-access cable TV, or in the Sunday evening special experimental series on Public Television. We all know that image quality on Youtube is poor. It’s not that much different from a painter’s work being reproduced, in miniature, on an Artforum page. We all know that the real thing looks so much better. The same thing holds for Youtube.

Artists give passwords to their Vimeo page, where potential collectors are able to preview their work – also in low resolution. In the old days, artists sent around slides of their paintings and sculpture. Now, artists have informative websites with images, pdfs of articles, their bio, etc.

Well, I think a lot of them use both, actually. But Vimeo…

Vimeo has better quality. When I teach and young students ask me: “what do you think if I would put up my work on Youtube?” I say “ You’re young, and Youtube is a way to get your work out and known… Spend time developing your ideas, and understand what and why you’re doing it instead”.

Doesn’t this way of distributing art comment on art as a commodity?

Occasionally, artists who are in the position of successfully selling their media art work will, sometimes, put a special work up on-line for everyone to access. This goes back to the utopian days of early video—when artists wanted their work to be accessible to all who were interested, rather than to just a select few...

I was at a gallery show recently where they actually streamed the Youtube-clips on a computer, as a part of the exhibition…

Someone like Cory Arcangel has done that kind of thing. He’s astute and would be commenting upon what the technology is, where it’s going, and what art is.

But at the same time, it’s not like you can really buy a Youtube-video…

I would imagine that the reason for showing a Youtube-clip in a gallery is to make some kind of a comment. Some collectors are interested in acquiring something that they see as an investment, and will be able to sell later. I only hope people acquire an artist’s work because they’re committed to the work and to the artist’s ideas.

Lets go back to your exhibition Soundings: A Contemporary Score. I always imagine that sound art has to be connected to an object.

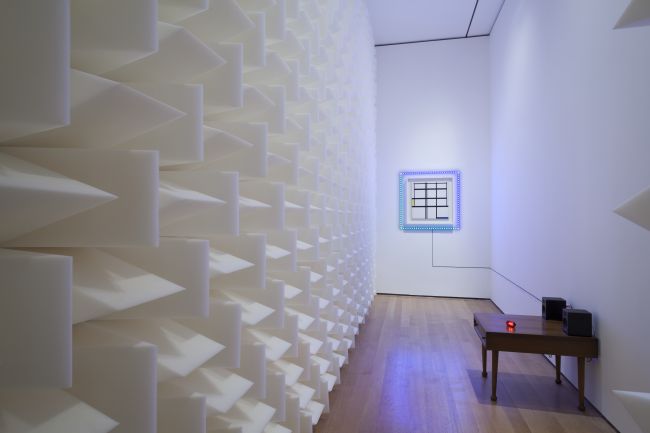

“Sound art” has many dimensions. My show is not a history, but rather, is meant as a look at the practice today. My major limitation was space—and I worked hard with the exhibition designer to create spaces that contain sound. Sound is fugitive; it moves far, quickly. The exhibition includes sonic installations; installations that incorporate video, in addition to drawings and sculpture. Sound is at the core of each work by the 16 artists. I made a decision early on, not to present work through headphones. Everyone walks around with earbuds, so why should they go to MoMA and have to go inside themselves? I wanted to create more social experiences.

How did that work sound-wise, between different pieces?

I worked hard with an exhibition designer and MoMA’s a/v team to create distinct spaces, rooms, and designated areas for work. In the case of the sonic installations, the museum-goer would walk down a corridor and go around a corner. We used soundproof material in the walls. We created sound traps. The works I included were presented all at the same time, and they became environments in themselves. For her new work, Jana Winderen created an unusual sonic environment with 18 speakers. Many museum-goers stayed in place for the installations’ entire 18 minutes. Susan Phihllipsz’s sonic installation is 24 minutes. The collaboration between Tsunoda and Flower is sonic, and features a film and a slide projection that collide on a fluttering cloth screen.

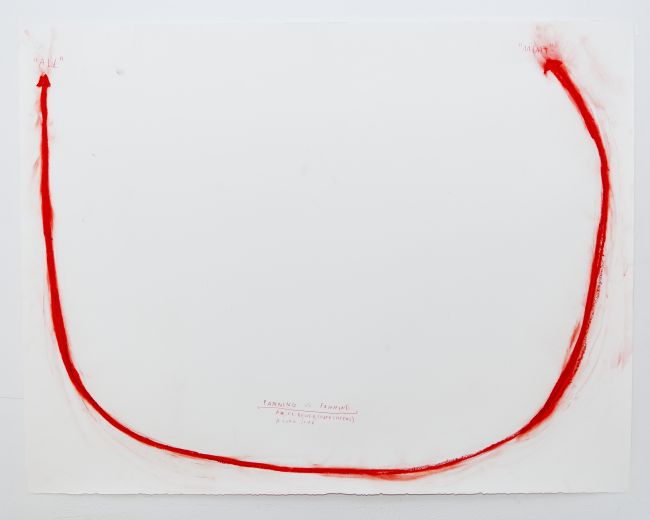

I chose to include drawings by two artists, Christine Sun Kim and Marco Fusinato. Marco’s sound installations are ferociously loud, and would have taken over the entire exhibition space. His ideas expressed in the drawings relate to his noise installations, and to the noise music that he plays in performance. When you look at his drawings, conceptually, you hear noise in your head.

That makes me think of Kandinsky, who was also influenced by sound in his paintings… it makes sense to be able to see sound. Do you feel that the attitude towards sound art and video art has changed in some way?

I think there’s much more of a comfort level with sound that has developed slowly, because of video. Walking into a museum, visitors are not that surprised to see a video-sound installation in a contemporary exhibition space – what you might call a “tuned environment.” Today, everyone seems to walk down the street holding a tiny device and wearing earbuds. So, there are many reasons why so many younger artists are working with sound.

They grew up with it…

Exactly, it’s a material that they grew up with.

How would you describe your role as a curator, in relationship to the artists that you work with?

There’s the museum, the institution, and there’s the curator. The institution has its point of view, its own way of telling the story of 20th and 21st century art. I respect and am guided by that. I have figured out where I can push and where I can’t. Traditionally, MoMA has always seen itself as an educator also. My role as a curator is as a kind of mediator between the institution, the artist, and the public. While I may have my own point of view, I want to represent the artist’s vision as best as is technologically, humanly, physically, and economically possible.

Media is still so new. We are fortunate that many of the artists who created the work are alive. I was privileged to have known such artists as Nam June Paik very early. Paik was a kind of mentor. What interested me in being in Stockholm was thinking about who he met while performing here in the 1960’s. Nam June had such a curiosity and an interest in pushing listeners’ limits. He was all about change, about experimenting, about learning from failure and moving on.

Christine Sun Kim. All. Night. 2012. Score, pastel, pencil, and charcoal on paper, 38.5 x 50

Would you describe it as a close relationship? The one between the curator and the artist…

As a curator, I always have felt that the most important part of my role was to be open, to look and listen carefully, to be honest, and when I didn’t understand something, to ask questions. Rather than describe the relationship as close, I feel it’s important to have some level of formality, but a comfortable and respectful one.

I’m from New York. Early on, I realized that many of my MoMA colleagues tended to look towards Europe, and going there to do research. So, I looked in the opposite direction – towards Asia. In the 1970s, I received a travel grant to go to Japan. I researched work and organized a show of video by artists living in Japan. I went knowing that I didn’t want to travel under one umbrella; in other words, to be limited by the vision of one person, or one entity. Remember, this was pre-Internet, the time of letters, when it took a long time to communicate with people. I found out as much as possible by reading, by talking with Paik and others who had been there. I wrote lots and lots of letters. When I arrived, a very lovely artist in Tokyo, Fujiko Nakaya, and her mother hosted an extraordinary dinner in their home, where I met 16 artists all at once. Then I was able to do studio visits, one by one, with each of them. I knew that I’m culturally different, so I had to really work hard to do research. (I had the same approach in going to China fifteen years later.)

I went on to study Japanese. So later, when I had a sabbatical in Japan, my language skills made a really a big difference. If you know the language, you can go deeper into a culture.

So, what artists do you find interesting right now?

Of course, I’m right here now, so…being in Gothenburg was fascinating. In Stockholm, I thought, “Oh I should go and see Johanna Billing.” We spent several hours talking together about her work, and that was really fascinating. I learned a lot.

I also caught up with Ann-Sofi Sidén, and realized that I had seen one of her installations in Venice, and another one in London. You begin with one level of understanding, but then meeting and talking with an artist like Ann-Sofi was meaningful. And that’s what the great joy is: now that I know more, there will be another step.

What are your plans for the future?

Now I’m very focused on writing.

What are you writing about?

Much like the “Soundings” exhibition, projects need parameters. You can’t take on the whole world. I’m thinking about how video morphed slowly into media, looking into how several artists’ geographical and cultural context has shaped their work.

It sounds kind of like map of video and media art.

A little bit.