“Nordic Art Today: conceptual debts, broken dreams and new horizons”

Daily life after the discotheque: what worries Nordic art, and what is it dissatisfied about

Dmitry Golinko-Wolfson

15/12/2011

1

If one were to schematically describe the development of art in post-soviet St. Petersburg, the history could be divided into two opposing stages. The first – the turbulent rebuilding of the 1980's; after that, the bitter 1990's of Yeltsin: a time when the youth subculture actively acknowledged itself and was oriented towards radically rejuvenating the core of the city's art life (see “the new artists”, “the new composers”, “the new critics”, “The New Academy of Fine Arts”, etc.) The artistic environment's aspirations of attaining unprecedented creativity, together with a faith in underground and unofficial cultural values, allowed the city to become a center of intense bohemia and art for more than a decade and a half. In the 90's, St. Petersburg turned out to be especially fertile ground for various groups of artists extolling alternative life-style scenarios and the creation of existential forms through squats and non-commercial galleries. It was at this time, the 1990's, when the mythological image of St. Petersburg as a territory of creative freedom came about; a place where the artist is not bounded by market dictates and, instead of realizing concrete projects, he can play character games (such as be a dandy, a loafer and a much-loved guru, all at the same time).

The second stage – the Putin “slowdown” years of the 2000's; the famous time of economic stability and then the following financial crisis, which was governed by the flow of money from raw materials. With few exceptions, St. Petersburg's art at this time looked inert and stagnant; its potential for creativity had been practically lost. The function of social critique, so characteristic of today's politically armored Western art, was pushed to the peripheries of St. Petersburg's public attention. In masses, artists turned to the financially rewarding work of creating objects of design for the post-soviet middle-class. That's why, in the second half of the 1990's, St. Petersburg's art was rather isolated from world trends; in addition, it gave off an air of provincialism when compared to the pompous and fiscally inflated situation in Moscow.

Grigory Yushchenko. “Don't Rip That Off, It's Important!” 2020-2011

It seems that it's not always possible to translate the local problems of St. Petersburg into the language of the world's cultural society. In the same way, not all issues important in the world cultural process are always adequately recognized and understood in the context of local art. Even though information technologies (firstly, the internet) may be well developed in St. Petersburg, especially among the youth, a certain “cultural famine” can be sensed. That's because in the first decade of the 21st century, structures for art education were practically non-existent (although there were liberal educational institutions such as “Pro Arte” and “Smolny College of Liberal Arts and Sciences”). In such a troubling situation, the vast exhibition, “Nordic Art Today: conceptual debts, broken dreams and new horizons”, is a hopeful sign of belonging to the international context.

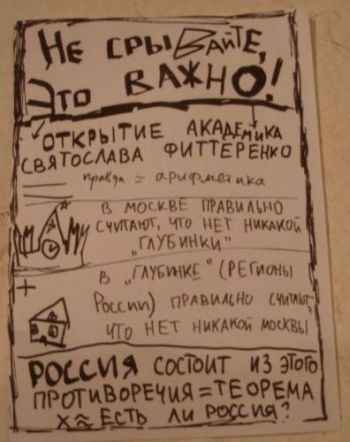

Loft Project Etagi

It is interesting that the exhibition is being hosted by Loft Project Etagi, which is found in what used to be an old bread factory; following the example of the Moscow Wine Factory, in 2007 Loft Project Etagi converted the space into a modern art center with several galleries, design studios and a hostel. At the time of Loft Project Etagi's founding, its segment of the cultural audience was socially transparent: they were the new specialists in the industries of design, fashion and nightclubs, among others. The phenomenon of contemporary art was centered by its growing prestige in the market – the aura of the surrounding rule of commercial success. After the financial crisis of 2008, this glossy environment wasn't as socially homogenous as it once was; in addition, its burning interest in modern art was quickly extinguished. In short – the glamorous public from the “upper floors” moved to other places, where hipsters gathered, but the Loft began attracting an extremely diverse public. Even though it wasn't swarmed by crowds every day, it was good to see that the exhibition was never lacking in visitors. I'm not sure if any monitoring of the public went on, but I believe that most of the visitors were students provoked by the cultural famine and young people associated with art, trying to fill in the gaps in their educations.

2

I'd have to say that the exhibition quite precisely and carefully reveals the thematic repertoire that worries today's Nordic art – artists from Scandinavia, Finland and Russia's Northwest. The main indication was the exposition's dispassionate, from-the-sidelines objectivity. This display of objective, Nordic art came about from the putting together of a rather complicated, branched-out team of curators for the exhibition. In 2010, the “Creative Association of Curators” (CAC) put forward the cultural initiative, “Nordic Art Today”, with a time-span of five years. The association's founders, Ana Bitkina and the sociologist, Maria Veits, work in both the project's conceptual and administrative parts. Consequently, alongside their curatorial work, they must deal with production and fundraising. CAC came out with a branching structure that fostered direct project realization. To represent local art scenes, CAC invited nationally representative curators who have already achieved professional reputations, but are not (yet) stars: Aura Seikkula from Finland, Simon Sheikh from Denmark, Birta Gundjonsdottir from Iceland, Kari Brandtcegs from Norway, Power Ekroth from Sweden and Ana Bitkina from Russia.

Goran Hasanpur. “Tower of Babel” 2011

Such collegiate work on the exhibition (based, in part, on Nicolas Bourriaud's idea about relationship aesthetics) allowed the curators to do a multilevel examination in choosing what to exhibit. As a result, the whole project was subject to a pathos stemming from constructive cooperation, instead of subject to the authoritative whims of a single curator. In addition, the continual international dialog going on during the creation process of the exhibition allowed for a clear definition of the curators' message – today's Nordic art doesn't exist as an ideological, territorial or value-based union; we are dealing with various forms of individual tonalities and treatments, with a conflict of interpretation based on clashing national traditions or differing descriptive discourses: neo-Marxism, post-colonialism, feminism, etc.

In my opinion, this is a very “correct” message: today, Nordic art (just like art from many other regions) doesn't have a unifying and defining criterion. Which is why, when discussing this art, many separate viewpoints must be understood, each of which states its own existential truth. I must admit that, on the backdrop of St. Petersburg as a whole, this exhibition appears “correct” and smartly made: it speaks to the local viewer in the language of world values and gives him an invaluable educational resource.

Russia's cultural management, especially that which is funded by state subsidies, tries to make cultural events and art happenings into expensive shows. Surprised by the immense funding going to worshiped stars and the accompanying banquets, the world must be shown the strength and ambitions of Russia's natural resource capitalism.

In the exhibition, “Nordic Art Today”, another method is put to use – a much more western and successful strategy. The product of the cooperative creative work between the curators and artists is research – a process that is collective, intellectual and at the same time, completely practical. A process in which the mission of today's art and the anthropological dimensions of human experience during the current crash of socio-economic formations is complexly sensed. And instead of attracting stars with huge fees, the curators have chosen to popularize new, not-yet-widely-known artists, who have the potential to become leaders of the art stage.

In addition, Russia's cultural management stands out with its extreme bureaucracy and its administrative cynicism, whereas the Nordic Art Exhibition encourages viewers to (re)evaluate the basic tenets of social democracy, such as honoring human rights, state economic regulation, justice and equality, security of private property, ridding social inequality, and others. With the current neo-liberal dictate, it is these aspects that create the platform for open, international dialog.

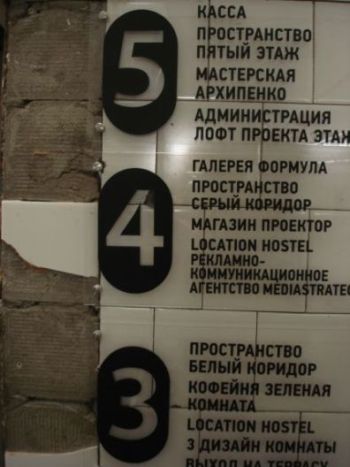

Allen Grubesic. “I Was Young...”. 2007

Nordic art (and all of today's art) doesn't put an accent on revealing the historical connectedness of meaning on a world-wide scope, but rather communicates stories of real people, sometimes even very funny ones or the kind that seem unbelievable. 21st century art senses the systemic connections between people, including those that are intimate and friendly; it creates an aesthetic from something as mundane as simply moving within a space, where the whole world starts to seem like just one, huge transfer station; it puts light on the complex relationships between the arbitrariness of corporate capitalism and the wants of the little person, which are, as a rule, ignored. Only, in Nordic art, there is a pronounced disillusionment with (and fear of) today's life, because the deconstruction of overall welfare in the region has begun only recently; only recently did the socially-oriented state system start to collapse; only recently was financing of low-profit art projects reduced, only recently did the average middle-class person start to feel on his own skin the unpredictability of life in neo-liberal capitalism, where financial inequality is growing and social guarantees are disappearing.

3

That is why the main minor note in the exhibition is a depressive alarm signaling the inability to make do in the present (in place of the daily comfort zone, it has become something unfamiliar, scary; it creates the need to be either constantly fighting for survival, or resisting). The ineptitude to find oneself in the present, or a fatal contradiction with it, can be seen in several works. This psychological mood is visible from a post-colonial view in the video installation, “Looking for Donkeys”, by Nanna Debois Buhl – the work is dedicated to the fate of the wild donkeys which, in the 18th century, the Danes introduced to one of the Virgin Islands in their ownership. The same motif is seen from a feminist angle in an audio-installation by the group Goksoyr&Martens: behind the white doors of a hospital, one hears the moans and screams of a woman giving birth; they get louder as the viewer nears the aisle that would seem to lead into the hospital ward. This condition is illustrated in a meditative manner in the work, “Zero”, by the Norwegian artist, Bodil Furu: in a monotone and slowed-down manner, the video shows one day in the life of a young, rich Norwegian man – he is busy with the routines of daily life and is unable to find himself a place in debilitating melancholia; in the present he is sad to the point of despair, and he does not have, and never will have, a tomorrow.

Bodil Furu. “Zero” 2008

The plot-line weaving through the exhibition (which is also, at the same time, its frame-like casing; one could say – a heraldic construction) is a painful perception of the present, accepting it as a lost paradise, a disappearing Arcadia, which once promised universal well-being and equality. And that is why the artist goes on an imagined trip to the past, which is usually a made-up or alternative past, but it allows one to find out the reasons for the lost present (or at least to find in the past the compensating justifications for today's shortcomings). In her video, “Stalin by Picasso or Portrait of a Woman with a Moustache”, Lene Berg tells us about Picasso's contention with France's Communist Party (in 1953, the French communistic weekly paper, “Les Letters Francaises”, commissioned a portrait of the “father of nations” from Picasso, but the party ended up rejecting it.) In this way, the artist shows the irony of history's unpredictability and the attempts (not always successful) to replay the past, so as to improve the present.

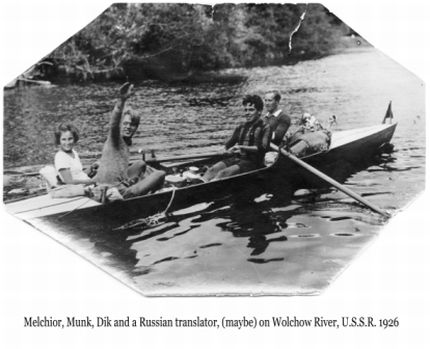

Eva La Cour. “The Free Look” 2011

Eva La Cour's media-installation, “The Free Look” – done with lyrical, nostalgic warmth – is a meticulously reconstructed trip taken in 1926 by three young, Danish communists. In a row boat, they rowed from Copenhagen to Leningrad and Novgorod, where they acquainted themselves with the nuances and details of soviet daily life. Mixing real documents with fictitious ones, as well as continually pulling down the fine and barely-sensed borders between the past, the present and the future, the artist brings one to the conclusion that this ancient journey in search of a communistic utopia invites today's viewer to think about an optimal or improved version of the future. Interestingly, similar attempts at finding a fantasy refuge in an alternative past was characteristic of Russian post-totalitarian art and literature of the 90's. At the time, cultural awareness was trying to survive – or speak about – the historical trauma that resulted from the catastrophic loss of connection to a world history project.

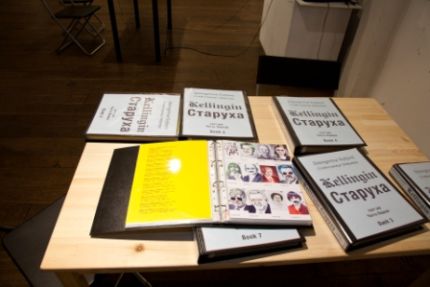

Steingrimur Eyfjord. “The Old Lady”. 2010-2011

A noticeable, even dominating part of the exhibition is created in connection with artistic documentation, archives and catalogs, which bring to the forefront the problem of self-classifying human experiences and states of psychological affectation. The Icelandic artist, Steingrimur Eyfjord, methodically, and on a daily basis, adds to his diary, which he calls “The Old Lady”. This diary is the author's collection of notes, interpretations, excerpts and newspaper and magazine clippings; it has all been translated into English and carefully bound in thick folders. Eyfjord lays claim to proving that today, all personal or collective biographical facts are definitely registered – either by our own accord or because of bureaucratic necessity.

Silas Emmery. “Found, Lost”. 2009

The project of the Danish artist, Silas Emmery, is a collection of photographs of the pages of photo albums, the pages being either empty or with fragments of photographs. The artist leads us to the idea that the workings of memory, which are based on a conscious selection of past images, will create zones of forgetting, or white spots in the cloth of memory, and will therefore be destructive in its way. The works of Scandinavian artists that concentrate on the questions of: 1) Do archives hide the past or reveal it? and 2) Are archives capable of erasing or bringing to the forefront the present?, are presented in a very ascetic manner, with minimal visual effects; this can't be said, however of the Russian (specifically, St. Petersburg) part of the program.

4

It should be taken into account that the Scandinavian curators mostly invited artists born in the 1960's and 70's, therefore, they had attained their professional maturity around the year 2000, after long years of study in academies and art schools in Europe and elsewhere in the world. When choosing artists from St. Petersburg, Ana Bitkina used principally different generational motifs. She included in the exposition artists born in the 1980's, who grew up in Putin's 2000's; their pragmatic views and career ambitions are in stark contrast with the idealistic and strongly romantic views of people whose ethical development happened in the full-of-hope-and-change 1990's (generational paradigm change in post-soviet Russia – that's a separate and long story).

The “Putin generation” artists consider the late introduction (just in the middle of the 2000's) of the post-industrial consumer generation into Russia, with its universal ideals of senseless consuming. But they don't reflect it critically or in a removed sense, but with an enthusiastic delving into the ideals of this society, with a slightly naïve consumer ecstasy, as seen from today's perspective. Many of the works of the new artists, whose careers began at the end of the 2000's, are meant for immediate cultural use, for a momentary reading of the whole code of content. That's why they try to be wrapped in bright and loud packaging, full of positive bravura and at the same time, give a slightly mocking “sting” (the Russian version of “fun”). Tatyana Ahmetgalyeva's video installation, “Cardboard Childhood, Paper Life” (12 monitors show paper dolls circling around), and Vlad Kulkov's sculpture, “The Order of Metamorphosis” (incrementally growing polyps of plasticine) are eloquent examples of new Russian art cultivating colorful, watchable entertainment, relaxed content of meaning, perception without effort, etc.

Tatyana Ahmetgalyeva. “Cardboard Childhood, Paper Life”. 2011

Obviously, the new Russian artist gives preference to the genre of effective and colorful shows, in the hopes that he will be noticed and will quickly ascend into the awards system, maybe even gain world-wide acclaim. But it is this tendency towards momentarily perceptive visual effects, instead of towards sympathetic social critique, that gives today's Russian art a kind of conceptual “immaturity” (in the exhibition's catalog, Ahmetgalyeva's work is described as a “pathological unwillingness to grow up”, that is, not taking responsibility for social faults). I think that the generational cross-section represented in Ana Bitkin's exhibition is very, very precise and symptomatic.

Tatyana Ahmetgalyeva. “Cardboard Childhood, Paper Life”. 2011

Pessimism, confusion, uncertainty of the future, mistrust of the competent institutions of authority – these are the main dominants that may not speak of outright tragedy, but they do speak of the anxious feelings of Nordic inhabitants in the situation when the social state has collapsed and neo-liberalism has come in its stead. I must admit that the project's curators vigilantly react to challenges faced by today's people in this unpredictable and inescapable era of transformation.

And so, Simon Sheikh asks: “What does the future have in store for a society that is in love with itself and just recently proclaimed itself the happiest country in the world – the Danes? And what does this society expect in a time of global economic changes and the downfall of sovereign nation-countries?” Aura Seikkula sees as the goal of her curatorial work “to ensure a process of criticism and questioning which is not dialectically opposed to an answering process, but affirms truth as the relationship and interaction between thought and reality.” A more dour analysis of the present is offered by the Swedish curator, Power Ekroth, who says, “The “new horizons” of today's Nordic art – that is something like a sober weekday after a fun discotheque”.

It's hard to predict what will be the daily life of art for all of post-industrial civilization in the explosive 2010's – will it be industrious or full of protest? Happy or sad? To the project, “Nordic Art Today”, which is planned to continue for several more years, I would like to wish the ability to come up with in-depth answers to these as-of-yet unanswered questions. Another important wish – that this project, as it evolves, gives increasingly clear and precise specifics of the social and cultural differences that characterize (and will continue to characterize) today's art in the Northern regions and beyond.