The most vibrant and memorable art event of 2017

27/12/2017

In 2017, social tensions were just as high in art as in politics. The day after Donald Trump was inaugurated President of the United States, women throughout the world united in a march to defend their rights. This was a stimulus for a sharp rise in female/feminist art in both global and local cultural spaces. February saw the opening of a solo show featuring the work of the grandly influential American/Brit David Hockney at the Tate Modern, while in May, Damien Hirst surprised the world with a bronze sculpture of Mickey Mouse ‘salvaged’ from a submarine. As if this wasn’t enough, the Louvre Abu Dhabi finally opened – it is not only the most ambitious new museum project in the last few years, but also the largest art museum on the Arabian peninsula.

As 2017 comes to a close, Arterritory.com invited several art world professionals to comment on which art exhibitions or events over the last year left a durable impression on them.

Julien Robson, Director of Great Meadows Foundation, the INhouse Foundation, and Curator of the Shands Collection:

Exhibition Intuition, at Palazzo Fortuny during the Venice Biennale, 2017. Exposition view, publicity photo.

For me, the most memorable exhibition was Intuition at Palazzo Fortuny during the Venice Biennale. It seems like a long time since I've seen such a poetically curated show and it made me nostalgic for 1980s shows like The Mirror and the Lamp and Skulpturen Republik. In contrast to the hype and pizazz that accompanied Damien Hirst's show at the Biennale, Intuition came across as an authentic attempt to explore the mysterious in art. My big surprise was that, for the first time, I really started to appreciate Basquiat. Juxtaposing his painting with neolithic menhir figures was simply inspirational and so far removed from the New York art world. I like the way that Axel Vervoort resists simply telling a story or laying down an overdetermined narrative. By bringing together this broad range of works across many ages, continents, and genres, the exhibition made you think about/imagine/construct new and continually shifting meanings. I liked that the form of the exhibition was intimately tied to the space it occupied, so that every turn of a corner brought new and surprising conversations between the works and the architecture. It felt human and vulnerable, while being a celebration of the inevitable passage of life. It was deeply layered and textured, immersive and, for me, a beautiful and haunting experience. After reaching the top of the palazzo and participating in Kim Sooja's Archive of Mind, I really did not want to leave the building. The exhibition haunts me still.

Noemi Givon, Founder and Director of Givon Art Gallery, art collector:

The most vibrant, though not all that memorable, exhibitions were both the Documenta and the Venice Biennale’s general exhibitions at the Arsenale and the Giardini. It is hardly possible to add something new to the many words and texts that were already thrown into these huge pot au feu,so to speak, but I still want to add that both of these large-scale exhibitions seemed like an attempt to muster the answer of the distressed, which is a very troublesome position.

I would refer everyone to this article, which for me, identifies the problems of the Biennale this year.

Additional exhibitions in 2017 that were memorable were the two retrospectives for Jasper Johns and Mike Kelley; the fact that the unforgettable Vitto Acconci passed away this year should also be noted.

However, for me (and many others), the longest life-enduring and prophetic exhibition of the year was The Boat is Leaking.The Captain Lied., which managed to be historically, politically, visually, and critically correct.

Stepping out of the exhibition space, I wrote to its curator, Udo Kittelmann: ‘I came into the exhibition happy and left broken-hearted.’That is to note what happened in the world since this show was conceived and eventually executed and presented to the art public; namely, the exhibition forced me to face the horrible repetition of quite a few human disasters that occurred meanwhile outside of the artistic arenas.

Mr. Kittelmann took upon himself a true task, one which he fulfilled, and the red light turned on. Ironically, Damien Hirst really threw the baby out with the bathwater with the devastating exhibitions in Venice.

ref. fondazioneprada.org/project/the-boat-is-leaking-the-captain-lied

Christian Ringnes, art collector:

Tori Wrånes’ exhibition Hot Pocket at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Oslo, 2017. Photo: DJ Gud Junior.

Duet Elmgreen & Dragset sculpture Dilemma in Oslo Ekebergparken, 2017. Publicity photo.

That has to be the Norwegian artist Tori Wrånes’ exhibition at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Oslo. Her playful show, her strong, enigmatic performances and great sculptures. The art committee of Ekebergparken actually acquired one of her sculptures; it will be cast in bronze and then given a permanent placement in Ekebergparken.

Christian Ehrentraut, Senior Director, Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin:

Vlado Velkov curated show Odyssey, on Lake Möhnesee in Western Germany, 2017. Photo: Tanaz Modabber and Daniel Knor. Publicity photo.

Certainly the most surprising and fun yet challenging and curatorially precise show was Odyssey on Lake Möhnesee in Western Germany. Curated by the brilliant Vlado Velkov, the 10-days-only event completely took place in the water and visitors had to swim, row or sail from one work to the next. It included, among many others, works by Aram Bartholi, Fabian Knecht, and Yorgos Sapountzis, some of them coming from Olafur Eliasson’s master class at Berlin’s University of the Arts. After walking your feet off in Venice, Kassel and Münster, it was great to experience the works from this different perspective and to see how the artists had to relate and rethink their works for this new context.

Sigalit Landau, artist:

Robert Rauschenberg at MoMA, 2017. Publicity photo. (Photo credit: Dan Budnik).

Robert Rauschenberg at MoMA – a huge delight.

Joshua Neustein curated and created a fantastic small show at the Tel Aviv Museum called Panda. Oil pastels, wax crayons and litho sticks, collectively known as ‘Panda Colours’, gave birth to a unique body of work in Israel during the 1960s–1970s [as a kid we used them in kindergarten]. In the 1960s, sensibility painting seemed to have reached exhaustion; with oil pastels, the pictorial enterprise presented itself refreshed. Oil pastels have sustained exceptional intensity, important as well as unique to the place and time where it happened. Neustein did a brilliant installation in this show: combining the art with the art-handling materials and devices. The show is fresh in a mellow and literally colourful way – with nothing retro-ish going on. Hope!

Mark Gisbourne, curator, art historian and critic:

Wenzel Hablik exhibition Expressionist Utopias, Martin Gropius Bau museum in Berlin, 2017. In photo: Wenzel Hablik, Firmament, 1913. Publicity photo

There is always a delight when an artist from an earlier time period is rediscovered and the experience comes as a complete surprise. This year the recently reconstituted archive of Wenzel Hablik (1881-1934) was exhibited at Martin Gropius Bau, and the work was a revelation. A designer, painter, maker of interior installations and the like, the exhibition showed him to have been exceptional in presaging many aspects and attitudes of contemporary expression, and at the same time he was very creative in his personal synthesis of different media, art and decoration, art and lifestyle art, and, to a cultural attitude, subtly linked to ideas redolent of the present time.

Hedwig Fijen, Founding Director of Manifesta, the European Biennial of Contemporary Art:

Camille Henrot exhibition Days are Dogs, at Palais de Tokyo in Paris, 2017. Exposition view, publicity photo.

The Jimmy Durham show at the Whitney Museum of American Art; Lucio Fontana at Hangar Bicocci; the Istanbul Biennial this year!; Palais de Tokyo: Camille Henrot.

Katerina Gregos, Chief Curator of the Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (RIBOCA):

The best exhibition I saw in 2017 was The Absent Museum at WIELS, Brass and Métropole in Brussels. Given the lack of a museum of a contemporary art in the capital of Europe (where I also live) WIELS decided to organize an exhibition that takes the form of a hypothetical collection blueprint for a museum of contemporary art today, at a particularly difficult moment for Europe given rising nationalism, populism and economic crises. This ‘museum-to-be’ stresses the necessity for critical engagement with the social and political present as well as the need to re-consider history to reinscribe its absent or marginalized narratives. The Absent Museum takes a series of bold and relevant positions: it steers clear of commercially hyped artists which produce art for the 1% and it is an intelligent example of a ‘collection’ of critically engaged and socio-politically relevant art that, at the same time, does not ignore the importance of poetics and aesthetics.

Maria Arusoo, curator, Director of The Center For Contemporary Arts, Estonia:

Rebeka Põldsam’s Be Fragile! Be Brave! at the Kumu Art Museum, 2017. In photo: Anu Põder works, exposition view.

As unfair as it is, of course, the end of the year is more vivid in memory, and I have to say that performance played a big role in it. I was really touched by Maria Metsalu’s performance mademoiselle x (premiered at Kanuti Gildi SAAL) depicting the zombified state in which we live; also Kris Lemsalu’s performances – Heaven Everything Is Fine at London’s DRAF, and Going Going at the Performa festival in New York – were beautiful, poetic, and even melancholic travels thinking about death and time passing by.

Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon at the New Museum, which investigated the role of gender in contemporary art and culture at a moment of political upheaval and renewed culture wars, was a rather interesting overview/take on the topic, and exhibited many exciting works.

One of the best curatorial exhibitions that I saw this year was Rebeka Põldsam’s Be Fragile! Be Brave! at the Kumu Art Museum; it contextualised one of the most distinctive contemporary Estonian sculptors, Anu Põder, in an international context with artist such as Ana Mendieta, Alina Szapocznikow, Iza Tarasewicz, Ursula Mayer, and Katrin Koskaru. It was a really sensitive and sophisticated display that lit up Põder’s extraordinary practice.

Michael Klaar, art collector:

Exhibition Like a Moth to a Flame, at OGR Torino, 2017. Exposition view, photo: Andrea Rozeti.

A bigger one: Like a Moth to a Flame, curated by Tom Eccles, Mark Rappolt and Liam Gillick, at OGR Torino; and a smaller one: Instructions for Happiness, curated by Severin Dünser and Olympia Tzortzi at 21er Haus Belvedere, Vienna.

Viktor Misiano, curator:

Pierre Huyghe’s installation at Skulptur Projekte in Münster, 2017. Pierre Huyghe’s work After ALife Ahead, 2017, photo: Ola Ridal.

Most likely that would be Pierre Huyghe’s installation at Skulptur Projekte in Münster…

Milena Orlova, Editor-in-Chief of The Art Newspaper Russia:

Marta Minujín’s sparkling Parthenon of books, at the Documenta preview showing in Kassel, 2017. Photo: Roman Maerc.

Since I visit a great number of exhibitions in a professional capacity, it’s very hard to hook me emotionally. Nevertheless, there were a few moments in 2017. For example, two artifacts elicited powerful emotions in me: one was very large; the other, very small. I arrived at the Documenta preview showing in Kassel in the evening; I met with my Italian colleagues and we had dinner and then went for a walk. Suddenly, right in front of us, we saw Marta Minujín’s sparkling Parthenon of books. We all knew of this piece from photographs, but at nighttime and with the lighting effects, the cellophane columns appeared to be made of crystal. The whole thing looked like a sort of Flying Dutchman, somehow magical and unreal. The guard let us in, and under the starry sky we joyfully wandered throughout the building, trying to find our most beloved books from childhood in the ‘bricks’ of the columns. We found this memorial to banned books very moving.

The second story has to do with Cai Guo-Qiang’s exhibition October at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. For the Moscow exhibition, the famous Chinese artist had created effective installations from straw, birch saplings, and huge gunpowder paintings. This was all very big and impressive, yet in the middle of the exhibition he had placed a family reliquary in a small display case – two matchboxes on which his father, also an artist, had painted traditional Chinese landscapes with mountains and rivers. They were tiny but masterful, and created during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The history behind these matchboxes immediately became clear to me – the same sort of miniatures were also painted on matchboxes or strips of paper by Soviet artists sent to the gulag. This tiny world which no one could take away from an artist, even when their ability to work was taken away, literally brought me to tears.

Alisa Savitskaya, curator at The National Centre for Contemporary Arts, Volga region branch (Nizhny Novgorod):

Anne Imhof’s project Faust at the German pavilion. Photo credit: © Nadine Fraczkowski

Anne Imhof’s project Faust at the German pavilion – a complex network of architecture, music, choreography, and the visual arts – really deserved Venice’s Golden Lion. Immersing oneself in this four-hour-long structure made up of shapes, movement, sound and rhythms left a breathtaking impression, regardless of the continual inconvenience of the crowds and that one had to watch the performers through the backs and heads of others. Faust brilliantly demonstrated the space that exists between the body and reality – the space where personality is born.

Valentinas Klimašauskas, Program Director of the kim? Contemporary Art Centre, Riga:

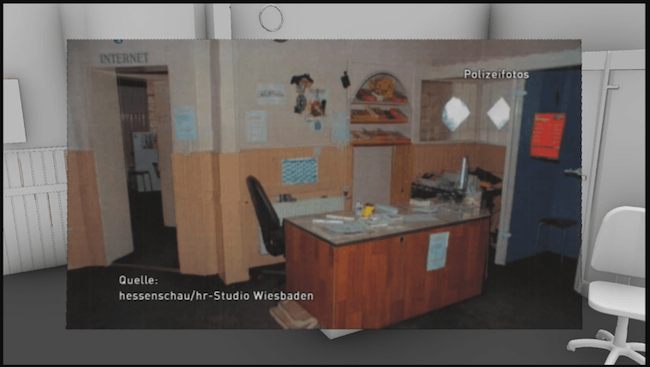

Forensic Architecture and The Society of friends of Halit video work Counter investigating the murder of Halit Yozgat in Kassel, 6 April 2006, at documenta 14 in Kassel, 2017. Publicity photo.

This was a memorable year for art, and if I must choose just one experience it would be Counter investigating the murder of Halit Yozgat in Kassel, 6 April 2006, a collaboration between Forensic Architecture and The Society of Friends of Halit at documenta 14 in Kassel, at the Neue Neue Galerie. The video is a scientific investigation, with artnet.com even declaring: ‘The Most Important Piece at documenta 14 in Kassel Is Not an Artwork. It’s Evidence’. Sincerely anti-racial and in search of the truth, it also tests the limits of our scientific, political and artistic imaginations.

A link: vimeo.com/220840144

Kaspar Mühlemann Hartl, Managing Director of museum in progress:

Georgian curating artists Mariam Natroshvili and Detu Jintcharadze project Museum of Contemporary Art suitcase, 2017. Publicity photo.

Recently our art initiative, museum in progress, had visitors from Georgia who brought with them not only a beautifully curated art exhibition put together for us, but an entire museum – the Museum of Contemporary Art Tbilisi. This portable museum, which was founded by curating artists Mariam Natroshvili and Detu Jintcharadze, is the first and only Georgian museum dedicated to contemporary art. It consists of a suitcase (!) in which a photo and video documentation of selected works are placed.

Olga Temnikova, gallerist and co-owner of Temnikova & Kasela Gallery:

METAMORPHOSIS, curated by Zdenek Felix at Kai10/Arthena Foundation, Berline, 2017. In photo: Maria Odry Ramiress, Sad Stingray & Stingray so so sad, 2016, photo: Julie Wieland

It’s very hard to choose, as there are many, and I truly enjoy the intimate gallery or smaller foundation exhibition format rather than blockbuster museum shows or biennales, so I’m going to name: the international group show curated by Oleg Frolov, Euroland, in our gallery; METAMORPHOSIS, curated by Zdenek Felix at Kai10/Arthena Foundation; Lodgers, curated by Veit Loers at Haus Mödrath; Paul Maheke at Galerie Sultana; Melodie Mousset at Salts in Basel; Merlin Carpenter at Galerie Neu, Berlin; the triple show of Marko Mäetamm curated by Jonathan Watkins in Riga (KIM?, Krassky, M2M bank); and many others…

Ivars Drulle, artist:

The Swedish film The Square (2017), 2017. Publicity photo.

My most memorable event is a combination of two events which I experienced a few days apart from one another. The first is the Swedish film The Square (2017), which is about life in the contemporary art world in a modern-day Western city.

More than a week after viewing it, I tried to find my own opinion, as a viewer, on the film’s complex construction in which irony, clichés, and existential dread overlap. Reconstructing the film anew from memory, I noticed that it consists of many small performances separated by short moments of respite. In addition, these performances are sometimes a part of daily life and only a couple of times are they clearly defined as art. I felt a pronounced emphasis on a blurry border zone in which art meets real life. Sometimes a meeting with real life can be very unpleasant. Or, the exact opposite – the janitor of the border zone can sweep up the embodiment of drifting art ideas and throw them into the rubbish.

The other event is hard for me to place in a clearly labeled folder, and it took place while I was still very much under the spell of the film. The UN war crimes tribunal declared that the 20-year sentence of a former Bosnian Croat general, of which he had already served 13 years after surrendering in 20014, was to be upheld. Standing up in the court of law, the former general, Praljak, stated: ‘What I am drinking now is poison. I'm not a war criminal.’ He then pulled out a small bottle and drank its contents. Then he shouted: ‘I am not a war criminal, I oppose this conviction.’ As we now know, the poison was deadly. How do we define what he did? Can it be called a work of art? Did he think that the people watching the live TV stream would be watching a fact of art? On one hand, sane thinking leads one to believe that it can’t have been a work of art, except for one ‘but’. Before the war of the 1990s, Praljak was a writer and theatre director, so the art world was definitely not foreign to him. What he did was absolutely a performance, and he played it like a rehearsed and carefully planned mini-show. And if a person with experience at writing and directing performs a performance, it can surely be called a work of art?! Not a single performer is yelling that what is happening right now is a work of art. Does a performance become a work of art only if there are invitations to the event strewn about on a café windowsill?

In conclusion, this year’s most memorable art event was these two events in which art bled into life within a contested border zone.

Dmitry Bulatov, curator at the the National Centre for Contemporary Art, Baltic branch (Kaliningrad):

This year a new trend clearly appeared in the projects of many artists, one which has now been labeled as ‘deep media’. These sorts of works try to find links and relationships based on data whose intrinsic value hadn’t been noticed or used up to now. I saw several new works that are part of this ‘deep media’ movement, one of the most interesting being the installation Jller, by the German-Czech duo of Benjamin Maus and Prokop Bartoníček. The artists had built a machine that, with the aid of a computer vision system, sorts river pebbles according to their age, texture and colour. The piece is named after the Jller River in Germany, which is where the pebbles were collected. Essentially, the robot is an industrial vacuum gripper equipped with a camera. Jller moves over a 2x4 metre-large platform, photographs each individual pebble, classifies it, and then moves it into place with the aid of a pneumatic gripper. In this way, a random assemblage of pebbles is transformed into an image that graphically reveals the river’s history. Jller is a rather finely-made artwork, so it is no surprise that it received an award at this year’s Japan Media Art Awards.

Māris Vītols, art collector:

Geta Bratesque works at Venice biennale, 2017. Exposition view, publicity photo.

Thick Time by William Kentridge, 2017. William Kentridge, The Refusal of time, 2012. Publicity photo.

In 2017 I was most inspired by the travelling solo show Thick Time, by South African artist and director William Kentridge, which could be seen twice – at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Humlebæk, Denmark; and at the Museum der Moderne in Salzburg. In 2018 the exhibition will be presented at the University of Manchester’s Whitworth Art Gallery. Moreover, Kentridge’s production of Alban Berg’s Wozzek at the Salzburg Festival was, for me, the most surprising and personally significant event to take place in opera in 2017.

In terms of the Baltic States, a definite mention should go to Polish artist Magdalena Moskalewicz’s exhibition The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe, which can still be seen at the KUMU art museum in Tallinn through January 28.