A biennial with a voice

Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2018: Possibilities for a Non-Alienated Life. Till March 29

07/02/2019

The two weeks around New Year’s that I spent in Kerala were frenetic. There was a state-wide general strike for three days. Actually, two separate strikes. The situation brought public transportation to a standstill, closed stores and schools, blocked roads in some areas, etc. Only a few beach shacks defied the strike and furtively tried to stay open, although there wasn’t much point, seeing as the strong wind on the beach kept people away, leaving only the rubbish to blow around.

The first strike was organised in response to the controversial situation that arose at the end of 2018 at the Sabarimala Hindu temple in central Kerala, which had always been closed to women “of menstruating age” (from age 10 to 50). Last autumn, however, the ban on women was lifted by order of the Supreme Court of India, and two women entered the temple under police escort. This action provoked widespread protests among the religious population. The two women were forced into hiding, constantly moving from place to place to avoid the vengeance of religious fanatics. The temple, for its part, was demonstratively cleansed and purified. On January 1, approximately five million women in Kerala formed a human chain 620 kilometres long. This “wall of women” demanded gender equality and the protection of women’s rights. But, as often happens at a time like this, some global media reflected the situation merely as general unrest.

The second strike was a classic trade union strike. Needless to say, nobody was happy with either of the strikes. Kerala has only partially recovered from devastating flooding in August, which has naturally also affected tourism to the region, and any additional stoppages are just another blow to the state’s already weakened economy.

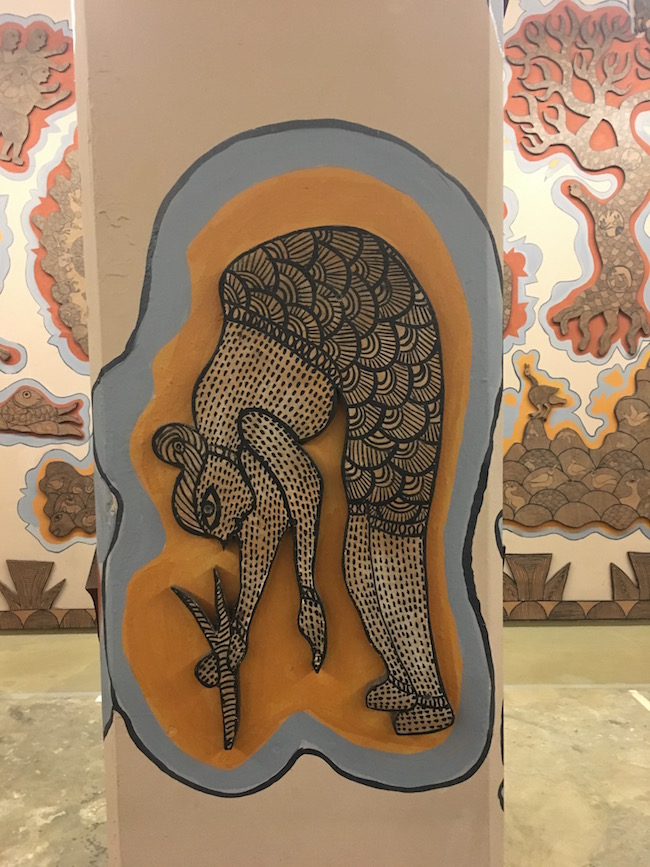

Durgabai and Subhash Vyam. Infra-Project, 2018. Photo: Una Meistere

Against this backdrop, I wasn’t very surprise when, at the small accommodation where I’ve come to feel quite at home over the past several winters, I was not brought a morning newspaper along with my black tea at breakfast. In other words: it’s in poor style to ruin a guest’s vacation with bad news. When I finally managed to get my hands on a copy of The Hindu, the pages were full of stories about well-known artist Subodh Gupta, who had been disgraced by the #MeToo movement. An anonymous woman with the Instagram username @herdsceneand had accused Gupta of sexual harassment, calling him a “serial sexual harasser”. This announcement opened the floodgates, and, although Gupta denied the accusations, he stepped down as guest curator of the Serendipity Arts Festival in Goa, bowed out of his annual participation in the India Art Fair in New Delhi and also withdrew from the Jaipur Literature Festival. It should be noted that Gupta is a patron of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, the biggest event on India’s contemporary art scene. But he is not the only one to be brought down by #MeToo. In October, that same Instagram user also unmasked Kochi-Muziris co-founder and artist Riyas Komu, who was subsequently forced to step down from his position at the biennial.

Anita Dube. Photo: Courtesy of Kochi-Muziris Biennale

Destructive flooding and #MeToo are only two elements in the dicey mosaic of current events that the fourth edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale must contend with this year. The exhibition is on show until March 29 and is one of the most powerful and provocative shows in the event’s history. Not least because for the first time it is curated by a woman. Anita Dube (1958) is an art critic, theoretician, art historian and one of the most radical of female Indian artists. A founder of the former Indian Radical Painters and Sculptors Association and the author of its manifesto, Dube once wrote that “art cannot remain apolitical”. She remains convinced of this statement today. The biennial she has curated is subtitled “Possibilities for a Non-Alienated Life”, and about half of the 138 represented artists are women. The event thus challenges the classic white-male hierarchy, which, although whitewashed by apparent gender equality and political correctness, is still the reality of the art world.

Later, in an email interview, Dube comments: “There is no question – to be a woman in the arts or otherwise is a fight, on many levels. I have had to face obstacles throughout my career due to my gender as well. I think it’s up to us to create networks and communities of solidarity where we support each other and each other’s work. I am very happy to see so many Indian women artists doing terrifically well, nationally and internationally, and I hope this continues.”

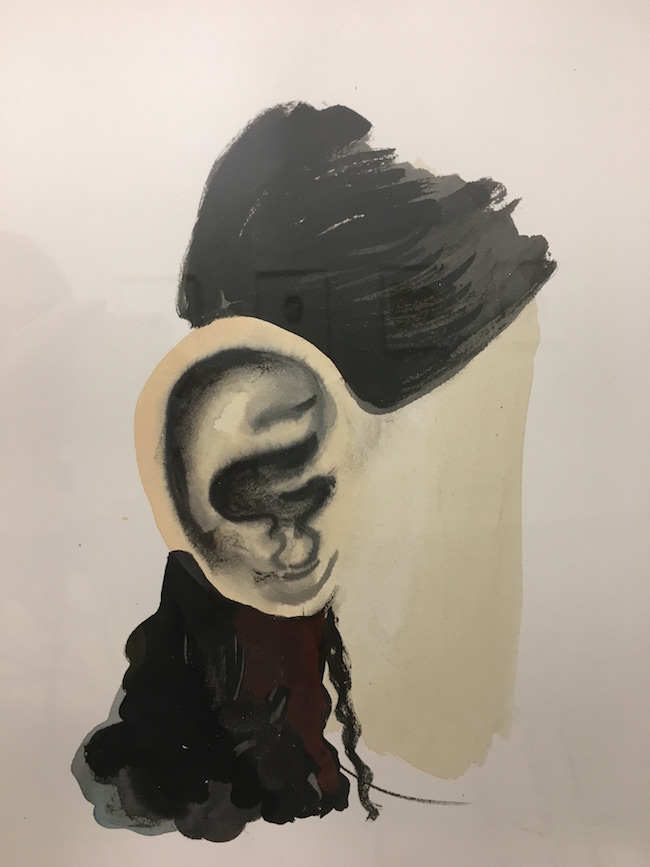

Marlene Dumas, 2018. Photo: Una Meistere

And not only that. In addition to many recognised Indian and international names (such as William Kentridge and Marlene Dumas), Dube has also provided a platform for lesser-known artists from conflict-ridden regions and marginal areas in the art world, among them a group of indigenous artists from Malaysia. In a way, her approach resonates with one of the concepts behind the strategic development of the Tate collection mentioned by that museum’s international collection director Gregor Muir in an interview with Arterritory.com: “I don’t think art is just one history – I think it’s many. And it’s going to be about many people as well. It’s not just about one kind of artist – it’s about people from different communities and backgrounds and traditions, and their stories have yet to be told. For example, referring to indigenous/First Nation art or Sami/Northern Scandinavian art (…). There is a need to reform the collective memory about what art is, and it should mean more to more people and be able to speak many languages.”

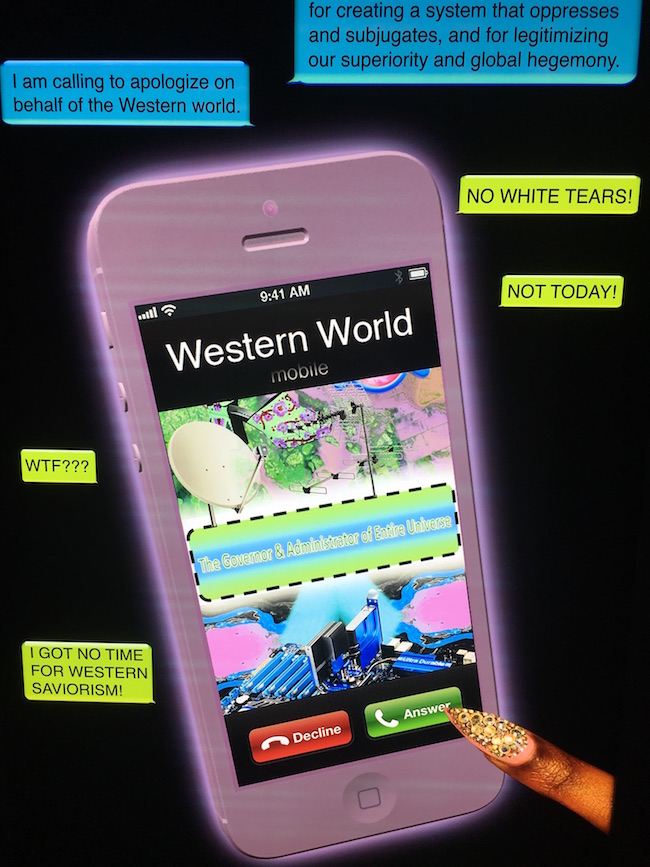

Tabita Rezaire. Sorry for Real Sorrow For..., 2015. Photo: Una Meistere

When asked about the choice of artists at the biennial, Dube says: “One of the most exciting parts of my curatorial journey was having the opportunity to interact with artists whom I’ve admired for a long time, as well as completely new practices. I knew that I wanted a healthy mix of these more seasoned and emerging artists, and the process was very eye-opening. Often, newer artists were chosen based on their response to my curatorial vision and the energy with which they wanted to respond. It was important to have well-known artists there, too, since so many people in India and Kerala would not have the opportunity to see their work in person outside the biennial.”

EB Itso Mr.Sun (Slow Violence), 2018. Photo: Una Meistere

In fact, compared to the previous curators of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, Dube has so far best managed to highlight the exhibition’s true identity, something that sets it apart from the rest of the many biennials that have sprung up in recent years all around the world. The Kochi-Muziris Biennale began in 2012 with the motto “This Is My Biennale”, its guiding principle a desire to be inclusive – inclusive of all art forms, religions, nationalities, opinions, persuasions and, what is particularly important in this region, also of the so-called non-art audience, or people for whom the biennial may be their first-ever encounter with contemporary art.

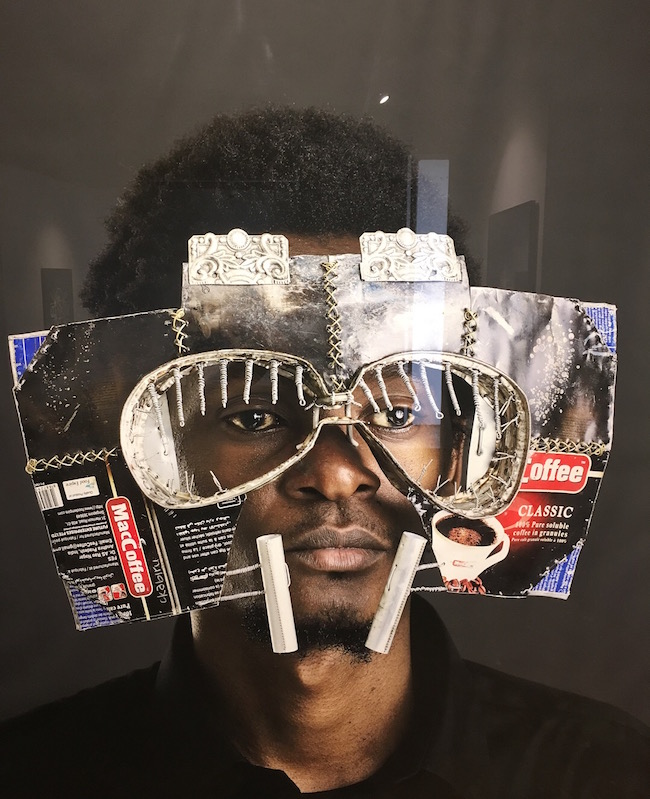

Cyrus Kabiru. Macho Nne series, 2016. Photo: Una Meistere

As confirmed by its previous editions, the biennial’s greatest strength lies not in the fact that it was born as an artist-led initiative, but rather in its ability to integrate this initiative into the local environment, its history and its modern-day context yet also mirroring global current events. None of the ten different biennial venues is a classic “white cube”; all are self-sufficient destinations in their own right and with their own individual histories rooted in the patina of the ancient port city of Kochi.

“I would say the venues of the biennial prove to be both a challenge and an advantage for curatorial and production work,” says Dube. “Given that many of these are heritage buildings, not made for the display of art, with uncontrollable climates and ‘open-air’ conditions, we have to take special care to ensure that each work is treated with the utmost care, especially easily perishable and organic materials. The heat can prove to be a problem, too, when there are high-functioning pieces of equipment like speakers and projectors running all day – this takes a different kind of meticulous maintenance. That being said, there is nothing like the biennial venues, which add an element of site-specificity to all the works on display. An existing work takes on a new aura within the spaces of the biennial, with their histories so evident in the architecture. Another advantage of the venues is how artists respond to them – to be part of this has been particularly exciting.”

Heri Dono. Smiling Angels from Sky, 2018. Photo: Una Meistere

The main biennial venue has traditionally been Aspinwall House, a complex of spice warehouses built in 1879 by British businessman John H. Aspinwall for his flourishing trade empire. The gigantic buildings stand right on the coast of the Arabian Sea, and the ships and barges still slide by its time-worn windows. Just a little further down the road are the famous and photogenic Chinese fishing nets, which can be seen on almost every postcard of the city. The Aspinwall buildings were restored only minimally for the needs of the biennial – basically only to ensure the necessary technical needs for the artwork and to prevent the ceilings from falling on visitors’ heads. Aspinwall is the essence of India: the India that seems to no longer exist but is nevertheless always present.

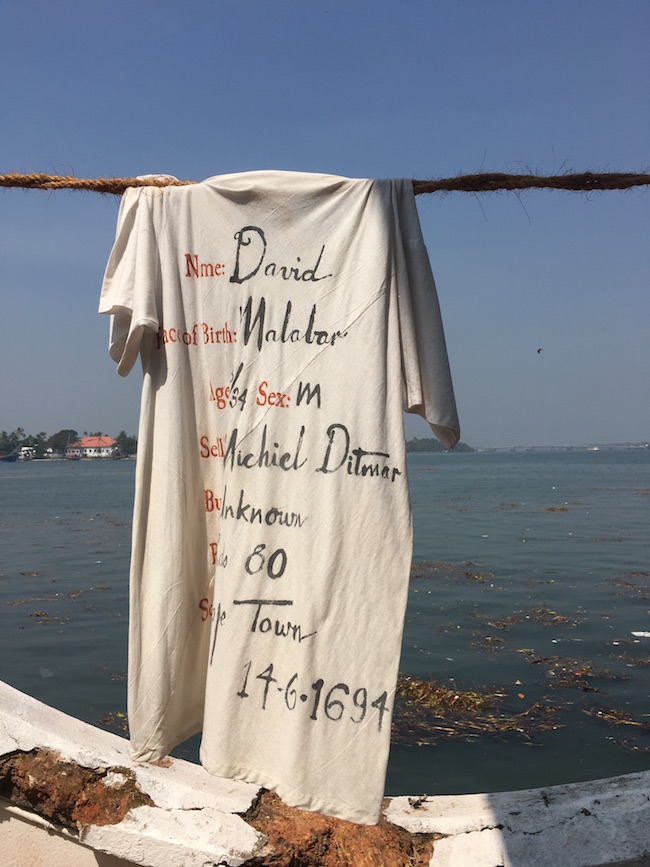

Even in the so-called winter season, the air in Kerala is thick, humid and saturated with dust, aromas and smells. White, well-worn shirts billow in the wind and sun on clotheslines at the edge of the water next to the biennial’s café (which, among other things, serves an excellent espresso to those weary of the swelter and art). At first glance, it seems that the shirts might be symbolically linked with August’s devastating floods. But take a closer look at the faded, handwritten words on them, and it’s clear that their story is in fact much older. The text on one shirt reads:

Name – David

Place of birth – Malabar

Age – 34

Sex – M

Seller – Michiel Ditmer

Buyer – Unknown

Price – 60 rupees

Sold at – Cape Town

Sue Williamson. One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale, 2018. Photo: Una Meistere

One Hundred and Nineteen Deeds of Sale by South African artist Sue Williamson documents one aspect of this region’s often-grim history. The installation consists of information the artist found at the Cape Town Deeds Office regarding Indian slaves transported (along with spices, Kerala’s most famous export) by the Dutch East India Company in the 17th century from Kochi to Africa, where they were then sold to work in the gardens and properties of wealthy colonists. Williamson made reconstructions of the flax shirts worn by the slaves and then wrote the scanty material available in the archives about 119 of them on the shirts. After that, she soaked the shirts in the muddy waters by Cape Town Castle, where the slave market once stood, and then brought them to Kochi. Here, during the biennial, they are washed at Kochi’s public laundry (which was formerly also used by Dutch officials) and then hung to dry in the courtyard of Aspinwall House.

Sue Williamson. Messages from the Atlantic Passage, 2017. Photo: Una Meistere

A second work by Williamson, Messages from the Atlantic Passage, follows a similar theme and is exhibited indoors at Aspinwall. It is exceptionally beautiful. Ironically (and nowadays so commonly), it also stimulates viewers to take selfies without delving into the content of the artwork. The installation features huge “chandeliers” made of fishing nets that hold “catches” of sand-filled glass bottles like the kind usually pulled from the depths of the sea in various mythical stories. The work of art is dedicated to 2500 slaves transported across the Atlantic Sea between the 16th and 19th centuries. Each bottle contains scraps of information found in archives about the slaves’ fates. Although Messages was not made specially for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale and has been exhibited before, Williamson herself states that never before has it been as effective.

Marzia Farhana. Ecocide and the Rise of Free Fall, 2018. Photo: Una Meistere

Meanwhile, Bangladeshi artist Marzia Farhana’s work Ecocide and the Rise of Free Fall reflects on a much more recent tragedy, namely, the August floods that took the lives of several hundreds of people in Kerala and destroyed homes and families. The large installation consists of household objects that survived the flood and were found in the nearby area. These objects, now hung from the ceiling, are like ghosts of consumer culture, phantoms of so-called urban progress: a fan, a Coca-Cola refrigerator, a washing machine, etc. Basically, all that remained “behind”. Signs of a littered world harshly bearing witness to a disaster whose perpetrators are largely we ourselves.

It was Kerala’s mountainous central region that suffered the most damage during the floods. The incessant rain led to unprecedented mud slides that swept away entire villages. The local mining industry (Kerala is rich in a variety of minerals), which in some places has bulldozed whole mountainsides, exacerbated the tragedy by having disrupted the natural balance in the ecosystem. The spaces where Farhana’s installation is displayed are small and dusty, full of the grime of civilisation; visitors manoeuvre between the objects, ducking instinctively every now and then to avoid touching any of them. Who knows what other avalanche or horror that might unleash.

“To be honest, I did not make a particular effort to ensure artists were responding to local issues, but these themes came out naturally, especially given recent events,” says Dube when asked how important it was for her to include artwork linked with the local context and current events. “That being said, I was very happy to have such a fantastic range of artists from Kerala participating in the biennial – their work is diverse and very vibrant. Another effort we took was to translate a number of text-based works into Malayalam, including iconic Guerrilla Girls posters. This adds a different dimension to their work and makes it accessible and pertinent in a different sense.”

The exhibition’s setting and context have also enhanced well-known Indian artist Shilpa Gupta’s sound installation For, In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit, which has previously been shown at the Yarat Contemporary Art Space in Baku as well as the Edinburgh Art Festival. It is dedicated to one hundred poets who, although they write in different languages (English, Spanish, Arabic, Russian, Hindi, etc.), are united by the fact that they have all been imprisoned for political opinions expressed in their literary work. The impressive installation consists of one hundred microphones and just as many steel “lances” on which sheets of paper bearing excerpts of the authors’ work have been stuck. A loudspeaker transmits one of the works, while the rest of the works quaver and shriek in the background, like a choir in a “hysterical symphony”. The youngest of the authors is Burmese poet Maung Saungkha, who was arrested in 2016 for writing a poem about having an image of his country’s president tattooed on his penis.

Jun Nguyen – Hatsushiba. Project Nha Trang, Vietnam: Towards the Complex – For the Courageous, the Curious and the Cowards, 2001. Photo: Una Meistere

Just as compelling an example of the interaction between setting and art is the video work Project Nha Trang, Vietnam: Towards the Complex – For the Courageous, the Curious and the Cowards (2001) by Japanese-Vietnamese artist Jun Nguyen-Hatsushiba. In order to see it, one must roll up one’s trousers or pull up one’s dress...and wade. The video is dedicated to the Vietnamese cycle rickshaws that have for decades transported people and things through cities and villages, at the same time providing employment for many locals. However, modernisation has made this slow but environmentally friendly mode of transportation unwelcome, and the government has banned their further manufacture. The aesthetically beautiful but scathing video shows a small group of young men trying to drive the rickshaws between the rocks and coral on the floor of the sea. They must periodically rise to the surface for air. Eventually, unable to continue their task, they abandon their rickshaws and swim to a mystical underwater “city” that perhaps symbolises the many Vietnamese boat people who drowned in the aftermath of the war. As viewers sit in the semi-darkness on pedestals made of wooden boards, the water sloshing around them to the rhythm of other viewers entering and exiting the “movie theatre”, their surreal similarity to the “swimmers” on screen becomes apparent.

William Kentridge. More Sweetly Play the Dance, 2015. Photo: Una Meistere

William Kentridge. More Sweetly Play the Dance, 2015. Photo: Una Meistere

Although the video installation More Sweetly Play the Dance (2015) by Johannesburg-born, London-based artist William Kentridge has already achieved chrestomathic status and been seen in many different places, its mythical procession gains a completely different depth when exhibited in the huge, dusty Aspinwall warehouse. Time seems to stop and merge with Kentridge’s characters, who join a dance in order to escape death and carry the past along with them in order to survive in the future. In the darkened hall, the viewers’ bodies spookily resemble the shadows on screen and are just as quiet – almost as if hypnotised. It’s not alienation; instead, it’s a naked, fully saturated sensation that everything is happening right here and right now.

Asked whether, living in such a politically, religiously and also socially complex country as India, she believes that art has the power to change society, Dube says: “Well, I hope that this edition of the biennial points us to ways in which we can do that. I think art has the ability to pose a possibility, or many possibilities, for living a different life. It’s up to everyone else to absorb that, be affected by it, and work towards making change. Even so, art practices are hugely diverse, and many of them involve direct engagement with activism and community-building. Some of these – Pangrok Sulap and Oorali come to mind – are in the biennial.”

Temsuyanger Longkumer Catch the Rainbow II, 2018. Photo: Una Meistere

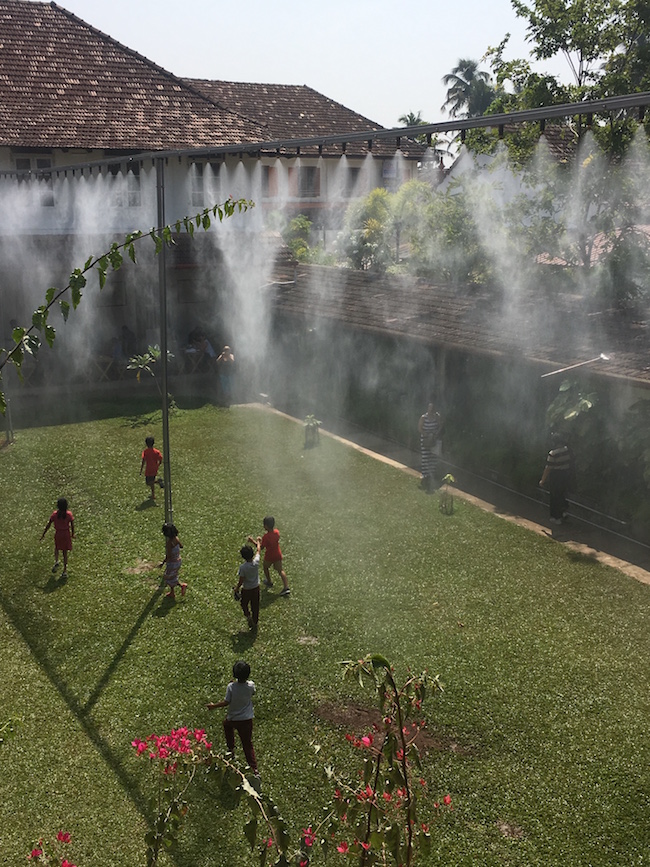

Another traditional venue for the biennial is Pepper House. Although smaller, it is also a former warehouse complex and features a ceramic tile roof dating to the Dutch era. A few years ago there were rumours that it might be transformed into a luxury hotel, but thankfully this vision has not come to fruition and the space is currently still available for use by the biennial. Some of the spaces at Pepper House are used as artist residencies; one wing houses a library and café. The symbolic heart of the complex is the large, green courtyard that is home to perhaps the most poetic piece of artwork at the biennial – the Catch a Rainbow II (2018) installation by London-based artist Temsuyanger Longkumer, who is a member of the Naga ethnic group and was born in Nagaland, a remote state in northeastern India. It’s a fountain that creates a rainbow in the sunshine and attracts all – big and little, young and old – like a magnet, evoking smiles and joy. In the early 19th century, Nagaland was a colonial territory along with other parts of India; later, it was made a part of the much larger state of Assam and regained status as a full-fledged state of India only in 1963. Longkumer’s installation combines an unpretentious primitiveness and magic and enchants viewers with its universal directness and immediacy.

“Art is conversation. And if there’s no conversation, what the hell is it about?” once stated classic conceptualist Lawrence Weiner. It seems that his words resonate directly with Dube’s curated biennial. When in Kochi, one has the feeling that art has, in some unearthly and rationally incomprehensible (to European minds) way, climbed out of the elitist shoes so hated (but also venerated) by the politically correct to take root in the streets along with all the rest of the city’s dynamism: dogs, cows, chickens, car horns, decorations from the Christian New Year and Hindu festivals and the general colourful commotion. There’s always a long queue at the entrance to the biennial, and it turns out that every other impulsively hired tuk-tuk or rickshaw driver is also well “integrated” with the art, nimbly offering to take his clients to all of the biennial’s venues. They’re just as natural destinations on the drivers’ routes as the spice market and the national “souvenir store”, where tourists are invited to spend at least half a minute looking around so that the driver can receive his free gasoline coupon.

According to statistics, the previous Kochi-Muziris Biennale (in 2016) had 500,000 visitors in three months. For comparison, the 57th Venice Biennale had 615,000 visitors in six months. When this year’s biennial closes in March, much of the material used for its construction will be donated to locals to build homes. In addition to an extensive educational programme, the biennial also hosted a large charity auction on January 18 in cooperation with the Saffronart auction house; the proceeds have been given to families who were victims of the August floods. Forty artists donated work to the auction, including Anish Kapoor, Subodh Gupta and Dayanita Singh.

“In spite of our hyper-connectivity, we are more and more alienated from each other,” Dube said in an interview. When I ask her whether she believes art has a unifying language and can become a unifying instrument/experience in our impetuous and unpredictable world, she says: “I don’t think art is inherently unifying or positive, or even should be. In fact, part of my curatorial vision was responding to the idea that art itself, within particular institutions and under capitalism, can be an incredibly alienating space. However, the idea is that opening up a platform for a multitude of voices and visions that are not often showcased can combat the idea of a biennial as an elite or culturally imposing space.”

And what is the key to a successful biennial? “Whether it’s effective! If a visitor walks away moved, in some way, by some of the works on display, and if the visitor felt free and welcome in the space, I consider that a success.” And in the case of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, there’s truly no reason to doubt that.