Agents of Life in the Territories of Death

About Lee Miller - one of the most important war photographers of the twentieth century

Kirill Kobrin

09/03/2016

‘Germany is a beautiful landscape dotted with jewel-like villages, blotched with ruined cities, inhabited by schizophrenics. There are blossoms and vistas, […] tiny pastel plaster towns, like a modern water colour of medieval memory. There are little girls in white dresses and garlands, children with stilts and marbles and tops and hoops; mothers sew and sweep and bake and farmers plough and harrow; all just like real people. But they aren't. They're the enemy. This is Germany and it is spring.’

It is late April 1945; it is indeed spring, and the author of this passage is driving in her army-issue jeep to the south of Germany – all the way down to Munich. In Munich, freshly seized by the Allies, the author, accompanied by her friend, the photographer Dave Scherman from the Life Magazine, visits the house of Adolph Hitler, as well as the flatlet of Eva Braun. The visit takes place on 30 April – the very day when the owners of this real estate commit double suicide in Berlin. I suppose the visitors were still unaware of this fact – however, it does not matter. They go through assorted household utensils – so pretty, so petit bourgeois, so gemütlich – homely. Tired from the road, they fight the temptation to go for a nap in the pristine bed of Eva B. Instead, Lee Miller – for that is the name of the author of the passage quoted above – decides to take a bath in Hitler’s tub. Scherman grabs his camera and sets it up in the bathroom; that is how one of the most famous photographs from the times of the Second World War was born. No, to be more exact – that is how one of the most famous photographs that concluded the war, providing a sort of symbolic summary, was born.

Lee Miller in Adolf Hitler's bathtub in 1945 Munich. © Lee Miller Archives, England 2015. All rights reserved

It is an almost perfect work of art. An ideally clean bathroom tiled in a light colour (the picture is black-and-white, so the actual colour of the tiles remains unknown). On the left, there is a sink; on the right – a special toiletry table with two drawers. Next to it – a stool, as light-coloured as the rest of the room. A white towel has been thrown on the floor by the bathtub to soak up the puddle that would form on the floor laid with small square tiles. The floor is dark. On the little table there is a small female nude statuette in the banally heroic style of Ludwig of Bavaria – Hitler’s favourite style. The figurine represents Beauty of the correct classical – Aryan – tradition. On the left, balanced on the rim of the bathtub, there is a photographic portrait of Hitler. I keep wondering: did Hitler really wash under his own watchful gaze? Why had the photograph been placed there? Or perhaps the bath was, in fact, intended for the use of Eva B.? Actually, we cannot rule out the possibility that these two sophisticated masters of composition, Scherman and Miller, had decided to add to the ascetic interior of the bathroom by planting a direct clue to the owner’s identity. It is difficult to tell. Either way, it is in this setting that Lee Miller is taking a bath. The snow-white towel is hopelessly stained by her army boots – heavy, with lots of straps and laces. Her army uniform is placed on the stool, folded quite neatly. As for Lee herself, she is looking somewhere up and sideways, not at the camera; she is scrubbing her hunched back with a sponge. Miller did suffer from severe back pains at the time: she had driven hundreds and hundreds of miles in her jeep along front-line roads, and it had had an adverse impact on her health.

Prior to Munich, Lee Miller had visited Dachau. There she had seen the doings of the sweet petit bourgeois couple whose involuntary hospitality she was enjoying now. In Hitler’s bath, Lee Miller is washing off the filth of his heinous atrocities and vulgarity which our heroine – quite predictably – attributed to the whole of Germany and Germans as a nation. What she had witnessed in Dachau (and before that – in Cologne, Paris, Saint-Malo and London) had shocked her not only due to the very simple and straightforward fact that, apparently, there actually were people who had made a conscious decision to exterminate other people, young and old alike, and had done it calmly, in a focused manner and even with some inspiration. It is something else that is important here. Lee Miller had discovered an aesthetic abyss between herself (and the world in which she was used to living) and these sweet Kleinbürger who had slaughtered half of the European population. Describing Eva Braun’s home, she wrote about her modern country style crockery and her white china hand-painted with tiny blue flowers. The furniture and decor, she wrote, was ‘strictly department store, like everything else in the Nazi regime: impersonal and in good, average, slightly artistic taste’. This article by Lee Miller was published in the July 1945 issue of the Vogue Magazine under the title ‘Hitleriana’. The source of the opening quote was also published in Vogue, in the previous – June – issue of the magazine; the article was entitled ‘Germans Are Like This’. As strange as it sounds, Miller was a war correspondent for this fashion and glamour magazine in 1944 – 1945; before that, almost from the beginning of the Second World War, she worked as a photographer for the same monthly. Her wartime works – complemented by additional materials dealing with Miller’s pre-1939 and post-1945 biography – are currently on view at the London Imperial War Museum. The title of the exhibition is ‘Lee Miller: A Woman’s War’. Weirdly, the photographer who is the author of thousands of pictures is known first and foremost from photographs in which she features as a model – not a creator. However, there are reasons for that.

Lee Miller was born in 1907, in a small town in the State of New York, to quite a well-off family. The wellbeing – or, at least, the staunch moral principles of the early 20th-century American middle class – turned out to be quite fragile. Two things happened to the young Miller, one of them – horrific, the other one – very strange. I suspect that both were connected. When Lee was seven, she once stayed overnight at the home of some family acquaintances; the girl was raped there by a grown-up man. The event was not only brutal but also mysterious: the Millers made no attempt to take any measures against the bastard. Moreover, the rapist infected his victim with gonorrhoea and Lee’s mother (who was a nurse) had to take care of the painful and humiliating medical treatment of her daughter in secret. Her father took the psychological rehabilitation in his hands. An ordinary engineer and manager by profession, he was into photography and all sorts of aesthetic nonsense; and so he had the absolutely brilliant idea to start taking nude photos of the poor Lee. All this horror went on for quite some time: there are extant nude photos by Lee Miller’s father of his daughter at the age of 18 – 20. Miller had to keep completely quiet about all of this; the secret was revealed only after her death. In any case, she took the first opportunity to leave her parent’s home and moved to New York. Lee Miller was divinely beautiful, a real angel in Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age style, so she did not find it difficult to get a job. She worked as a model for a number of fashion magazines and had some stints at cafè-chantant orchestras and dance groups until she eventually was noticed by the American Vogue. And that is how Lee became one of the most recognisable girls in the USA.

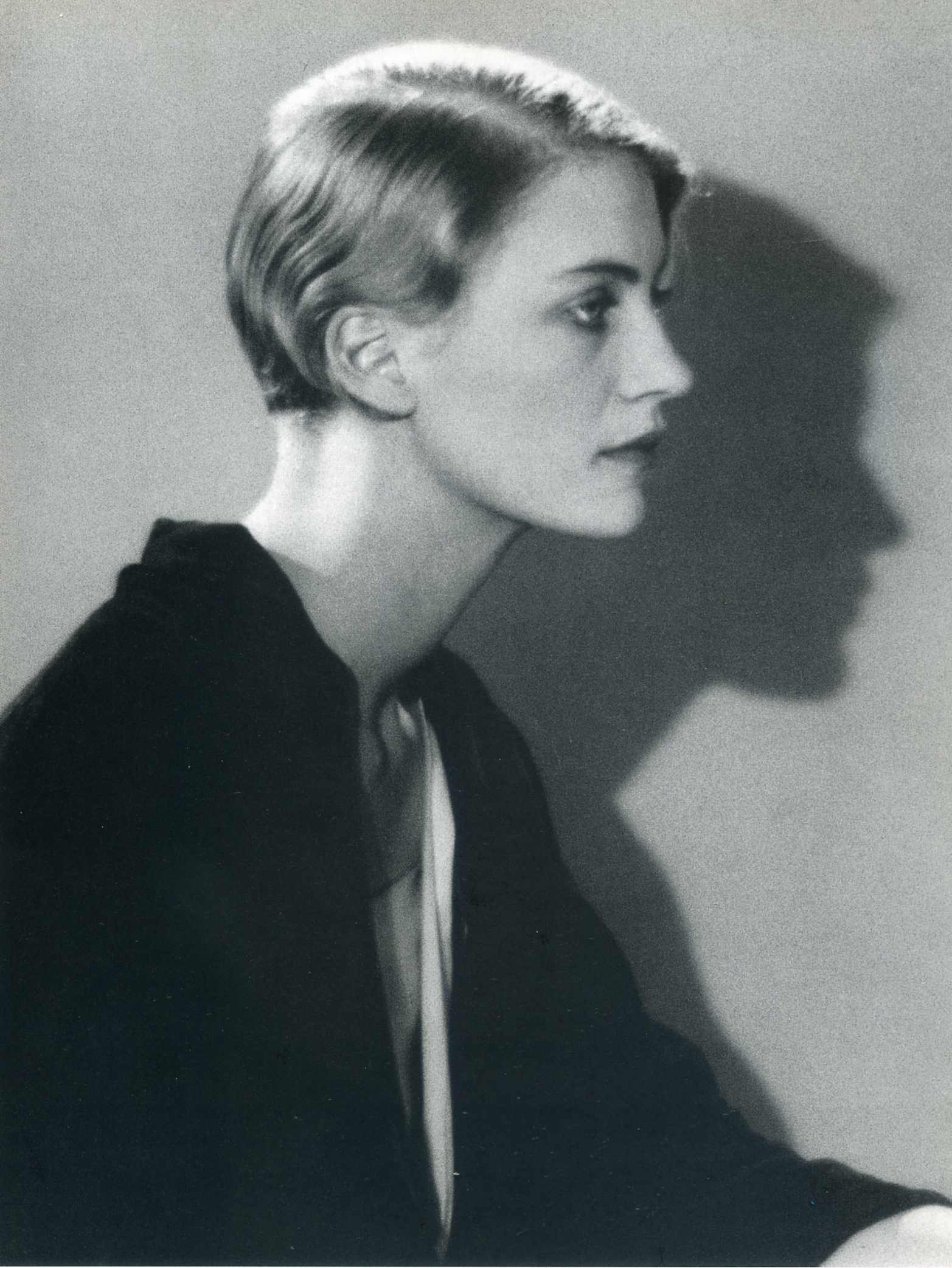

Lee Miller photographed by Man Ray, 1930

While continuing to pose for the magazine, she moved to France. This is where a completely new period in her life started: her apprenticeship with the Surrealists and affair with Man Ray who taught her photography. Lee Miller took part in Man Ray’s famous White Ball at the estate of the aristocratic family of Pecci-Blunt; she also played a role in Cocteau’s first film, ‘The Blood of a Poet’; Picasso painted her portrait. The Time Magazine, which ran an article on Man Ray, accompanied the publication with a photo of a half-naked Miller, announcing her to be the owner of the prettiest derrière in Paris. In 1932, having conquered everyone – or almost everyone – on both the left and the right bank of the Seine, Miller went back to New York. However, she did not stay at home for long, reappearing in Paris in 1934; from there she moved to Cairo, accompanied by her newlywed husband Aziz Eloui Bey. Nothing new about that – beautiful models and Oriental moneybags. Life among the Anglophone expats in Egypt, the company of Agatha Christie-esque old ladies and retired colonels from the Colonial Service was obviously not to the liking of Lee Miller, although it was there that she really found her passion for photography. And so by the late 1930s we find her back in Europe again – either in France or travelling in the south-east of the continent with her British modernist artist and collector husband Roland Penrose. Lee Miller got together with him very fast; it would seem that she should have left him as quickly – like she always did. It must be said that she was an advocate of genuine sexual liberation, a far cry both from the patriarchal notions of her homeland and the macho principles of many American expats from the Parisian art and literature circles – including Man Ray or, Heaven forbid, Ernest Hemingway. I have no idea if Lee Miller was spared the dubious pleasure of crossing paths somewhere in Europe with the somewhat obtuse inventor of the famous ‘cablese’ style of prose – but as for his brilliant third wife Martha Gellhorn, they definitely met in 1944 in France. Incidentally, the marriage between Gellhorn and Hemingway broke down due to the fact that this fantastic author of manly stories was incapable of tolerating his wife’s journalistic career – Martha Gellhorn was the world’s most famous female war correspondent at the time. Le Miller met Penrose – and, despite the various pitfalls and dramas of her later life, remained with him until her death. She had separated from Eloui Bey in the late 1939 but the couple would officially divorce only after the war, when Miller decided to give birth and mark the fact by marrying her partner. But meanwhile, immediately after the beginning of the Second World War, she moved to Britain and settled down with Penrose in a house in Hampstead. Their home became one of the bohemian bastions of the wartime London: they drank a lot, talked a lot and even danced a lot. However, Lee was not satisfied with that; she decided to launch a personal war with Hitler - even more so because the island where she had found herself was in mortal danger. France had shamefully capitulated; practically the whole of Europe was occupied by the Germans; the Luftwaffe were flattening Britain with their bombing; Stalin, having divided up Eastern Europe between himself and Hitler, thankfully supplied him with provisions and fuel; the USA pretended that the whole thing did not concern it. The country where Lee Miller had settled down almost by accident found itself completely alone against a hostile world. And so our heroine picked up her camera and went to war. The war was raging literally on her doorstep – in London.

At the exhibition on view at the Imperial War Museum, one of the sections is dedicated to women before the Second World War. The world of women’s magazines, the world of Vogue, unfolds in front of us, interspersed with scenes from the life of modernist bohemian circles. It is actually here that the aesthetic and ethical roots of Lee Miller, the photographer and the human being, lie – this is the fuel that powered the following six years of frenzied work, the six most intense years of her life. It is a somewhat weird mixture that we may find either impossible or banal today. On the one hand, what could be further from the harsh ascetics of modernism, these autistics, these sweaty paranoids, these unkempt drunks, than fashion and life of glamour with its ‘fat cats’, yachts and pink martinis? One of these worlds is open and enticing; the other keeps at bay every stranger, reserving particular contempt for the middle class – at least until the stranger parts with some money. On the other hand, the world of modernism has always been closely linked with socialite circles, all sorts of fads and even with mainstream media. And one of the three main Titans of modernist literature was a socialite amateur who wrote a great novel about upper-class loafers. Toulouse-Lautrec drew posters, as did Alphonse Mucha; Picasso always rubbed shoulders with useful people from the elite; Duchamp and Max Ernst were, in fact, a pair of gigolos. Moreover, contemporary advertising could not exist without modernism; one of its founding fathers was Salvador Dalí. There actually is no contradiction in this. And the fashion industry with the mainstream media and modernism – they are the spawn of the ‘contemporary era’, modernité, the two sides of it, the combination and balance of which has created the modern way of life with its inaccessible accessible world of fashion and accessible inaccessible world of art and literature. The fundament of this world, despite all the temptations of collectivism, is extreme individualism and self-reliance. Fashion is the opposite of mass production of clothes; the bohemian lifestyle is the opposite of the mass class society; modernist art is the opposite of vernacular, petit bourgeois and popular art. Of course, things have been different at different times, but Lee Miller’s credo, formed in the late 1920s and the 1930s, was exactly that. Furthermore, life of glamour and the fashion industry became the unlikely source of our heroine’s feminism: not a feminism of the abstract or theoretical variety (‘The Second Sex’ would not be written until two decades later) – a practical feminism. Miller regarded the world of women as a distinctive one, with laws and everything else of its own; however, she did not see it as an area of second-rate patronising interest but rather a universe as complex and important as the world of men. It was already obvious in her photographs dating from the 1930s; however, it was during the war that the special Millerian feminism came into its own.

At this point, a couple of words should be said regarding the ambivalent position that Lee Miller had invented for herself. In the old, pre-war life, men with cameras had been taking photographs of women. After a time working as a model, Miller decided that she wanted to become a photographer – without actually disappearing from the other side of the lens. It means that she did not commit the usual silly mistake of various rights activists who tend to prefer simply to exchange their place for another one that they have been yearning for. Miller decided to prove that you can be a photographer and a model – the one who takes pictures and the one whose pictures are taken. Moreover, eventually she – without giving up her role as a photographer – also transformed into a reporter, a word specialist. Throughout her life, she had been photographed naked or half-naked, thus demonstrating someone else’s power over her body; now, not at all waiving her right to seduce with her natural beauty, Lee Miller armed herself with weapons of ‘culture’, ‘progress’ and ‘technology’ – a camera and a typewriter.

.jpg)

Women in fire masks, Downshire Hill, Hampstead, London, 1941 © Lee Miller Archives, England 2015. All rights reserved

For some time, the editorial board of Vogue kept declining Miller’s proposal, preferring the services of their male staff photographers. Eventually they gave up: the men were drafted; besides, their former model proposed a hitherto unheard of subject: ‘women in the war’. That is to say, the subject had been dealt with before: there had been the final kiss before the troops’ leaving for the front line; there had been nurses and even nuns praying for victory. However, in 1939, there was already a different life where women were working in factories, fighting fires, driving trucks and even marching in formation. They were not often given real weapons; nevertheless, it was impossible to pretend that victory was brewing in a pot in the kitchen instead of being cast at a steel mill, as had been the case during the First World War. Besides, Vogue is, after all, a magazine about women for women; consequently, it needed to adapt to the not very elegant mundane wartime reality – without losing its charm and elegance. And photographer Lee Miller was very good at that. She was working somewhere at the intersection of the themes of ‘wartime fashion’ and ‘new female professions’ and photo-reporting; her subjects were either posing in elegant dresses against the ruins of a bombed London neighbourhood or blasting spotlights into the air in search for ‘Junkerses’; either marching to the meeting place of the Women’s Home Defence units or enjoying some carefree respite from their righteous daily work, almost recapturing the aura of the pre-war Vogue. Her photography can be described as ‘propaganda’ – but a very special kind of propaganda; it is not promoting victory or ‘our guys’ who are about to fearlessly beat ‘the other guys’ any minute now; no – what we are looking at here is propaganda of the value system espoused by the Western – excuse the banality – democratic society engaged in a battle with a throng (invisible in Miller’s photographs) of ghouls. Confronted with the Ultimate Evil, Miller’s women act in a completely normal way – which is the only way to win. And the whole country wins with them. Lee Miller managed to bring down the boundaries between ‘normal life’, ‘the world of glamour’ and ‘high art’ in a very subtle way – not completely, of course (no-one has ever wanted to bring them down forever), but the effect she created was amazing.

In fact, it was war itself that brought down these boundaries; in one of the issues of Vogue, Miller published a few photos of the conditions in which the editorial board was working, also providing a short commentary to the pictures. Outside – for several nights in a row, bombs had been falling within twenty yards from the office. A new crater had formed on the street overlooked by their windows; yet another span of the portico had been destroyed. The members of the staff had discovered and extracted a time bomb. Inside – the office rooms were scattered with shards of broken glass. Miller observed the weird way in which the blast wave from an explosion sometimes worked: a glass of water had not even cracked; not a single drop of water had spilt from it, whereas five floors up, everything had been covered with a thick layer of soil and rubble that had landed on people’s heads through the damaged roof. In the basement – this was where the editorial team actually worked when they received a warning from someone standing guard on the roof that it was time to run for shelter. People continued to plan issues of the magazine, make layouts, write articles. The magazine’s photographic studio was now set up in a wine cellar. The fashion experts continued to comb the shops. In these cramped conditions where there was not enough space for ceremonies yet more than enough for good relationship between co-workers, the staff of Vogue spent their days like all the rest of Londoners; when the night fell, they went to sleep in their bomb shelter. Despite everything that was happening around, the Vogue Magazine was still there. And despite everything that was happening around, life was still going on.

FFI worker (Forces Francaise de l’Interior), Paris, 1944 © Lee Miller Archives, England 2015. All rights reserved

In 1944, Lee Miller managed to obtain a war correspondent licence and, following the Allied forces that landed in Normandy, she headed for the Continent. This was a completely different situation: Britain had been bombed but not a single pair of enemy boots had tread on its ground, whereas here there were a multitude of boots and the locals were not always able to understand which ones belonged to the enemy and which ones were theirs. Miller continues to develop the subject of ‘women and the war’, although here and there we see some photographs featuring only men. What can you do? It is a war after all, and it is hard to avoid pictures of wounded sergeants and valorous captains – especially if you accidently find yourself in the vicinity of Saint-Malo besieged by the Allies. There are still more women than men. For Saint-Malo Miller was disciplined, even placed under house arrest – but it was definitely worth it. The exhibition features a photograph of an ancient street in this city; it is only on very close inspection that you notice a small part of an old woman’s face, worriedly peeking out from a doorway. But starting with Paris, we see full-length portraits of women – beautiful résistantes who fought the Nazis in their mousey uniforms not only with weapons but also with their elaborate hairdos and colourful lavish dresses; their opposites, collaborators and girlfriends of the Nazis – humiliated, shaven-headed; the very first Parisian fashion show after the liberation; so much more. The victory over the Nazis and their henchmen – it is a victory of life over a shameful and horrible world of the undead; it is very obvious to Miller, and that alone makes going to war with Hitler worthwhile. It is not the ‘Americans’ or ‘Brits’ fighting with the ‘Germans’: it is indeed a triumph of life – scary, unfair and flawed as it is – over death. And it is exactly for this reason that Lee Miller was so struck by the sight of the peaceful Germany, at first glance – untouched by the war, when she crossed the German border with the Allied forces in early 1945. It was only afterwards that she saw Cologne, practically wiped off the face of the earth, and somewhat later – other cities. But at the time she is driving her jeep and looking at the virginal purity of birch trees and fragile willow trees leaning over little streams, and she is also seeing this: ‘tiny pastel plaster towns, like a modern water colour of medieval memory. There are little girls in white dresses and garlands, children with stilts and marbles and tops and hoops.’ The girls also play with dolls. And immediately afterwards, Miller goes to Dachau.

Her contempt (no, not hate – contempt) for Germans, the result of these few months, was, strangely enough, not of an ethical nature. Miller is not a moralist; she does not condemn those who killed and those who supported those who killed. She is recording the final stage of the Nazi cancer as an aesthetic disease caused by pathetic philistine taste, mass production of sweet knick-knacks and the general German Gemütlichkeit. In this sense, a telling example is Miller’s photo of a suicide, a young woman from an influential Nazi family. The embodiment of the Hitlerite dream of the ultimate Aryan woman: strong, blonde, Nordic, she is lying on a sofa – dead, in a carefully studied pose. In fact, we could say that it is not simply a dead Nazi girl lying there – it is Death herself, the main object of worship of Hitler & Co. ‘I’ve never in my life seen such lovely and well-cared-for teeth,’ mutters Miller – dirty, exhausted, stinking of brandy and tobacco without which she would not have lasted a week of this life, and drives on. There is nothing to say and nothing to feel sorry for. These are people who had consciously chosen death – and death is what they got as a result. The horror lies in the fact that, between their point of departure and the end of the road, they had exterminated millions of other people – those who had not made this choice.

So it is this filth, this death that Miller is washing off her beautiful body in Hitler’s bathtub. It is as if she were shaking off a spell from herself and the rest of the world around her with this gesture. People who have survived still live in this world; they suffer; they must have a right to continue their life. Especially because there are others who, in the name of this very life, try to kill them – even now, when the war is already over. The disease has not been terminated; it has been passed on to the victors. Now it is they who try to do the same thing that Hitler did before them – in Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania. They drive people away from the places where they have put down roots; they torture; they put people in concentration camps; they summon death back to Europe. After spending a year and half or so taking pictures in these places, Lee Miller goes back to Hampstead – back to Penrose.

Two German women sitting on a park bench, Cologne, Germany, 1945. © Lee Miller Archives, England 2015. All rights reserved

At this point, the life of Lee Miller the photographer came to an end; what started was the longest and hardest stage in the life of Lee Miller the human being. She was paying the price for the five wartime years until her final hour – plagued by alcoholism, depression and social phobia. Miller hid all of her wartime photos in the attic of the Farley Farm House in East Sussex where she and her husband had moved in in the late 1940s. Although the former heroes of modernism occasionally did drop in at the Farley Farm House, no-one remembered about Miller the photographer – and neither did she. Gradually, retiring to private life for good, Lee Miller found an interest in culinary; according to her acquaintances, she developed into an excellent cook who challenged the dull British kitchen of the time (its drabness was further exacerbated by the fact that most products were strictly rationed in Britain until the second half of the 1950s). In a way, it was yet another challenge issued to the world of undead, only this time – on the level of flavours and taste. It was approximately around the same time in Britain that another great woman of the era of modernism and the war, Elizabeth David, launched a culinary revolution. It is thanks to Miller and David – and only them! – that in a country where olive oil, recommended against otitis and burns, could only be purchased at pharmacies as late as in 1957, today you can exist without knowing anything about fish and chips and the Yorkshire pudding. In her own culinary activities, Miller saw a sequel to the Surrealist revolution – which, to an extent, is correct: the average Brit at the time would look at salad and ratatouille pretty much in the same way that a Constable aficionado – at Duchamp’s urinal.

Lee Miller died in the 1970s, completely forgotten by everyone. Some time after her death, Miller’s son, photographer Antony Penrose found a box of photographs in the attic of Farley Farm House. Thanks to Miller’s son, we know about her the things that we know. And this knowledge makes us stronger.

Post Scriptum. An Addendum on Elizabeth David.

Elizabeth David (née Gwynne, 1913–1992) was born to a family with English and Irish roots. Her father, Rupert Gwynne, was an MP from the Conservative Party; Elizabeth grew up in a 17th-century manor house in Sussex and studied at the Sorbonne in the 1930s. When Gwynne was 25, she and her married lover Charles Gibson-Cowan decided to elope, leaving Britain; they bought a big motorboat with the intention of cruising along the Mediterranean coastline until they would have had enough. However, only a few months later the Second World War broke out. The lovers started dashing around the south of Europe, running away from the rapidly approaching German forces. From Antibes they moved to Corsica, from Corsica – to Italy where they arrived on the very day that Mussolini declared war to Great Britain. Their boat was confiscated by the Italian border guards, and the couple was deported to Greece. Elizabeth and Charles found themselves on the island of Syros where – with the rumble of the just-started war in the background – a sizeable group of British expats, the writer Lawrence Durrell among them, were having quite a good time. Those pesky Germans eventually showed up in Syros as well; however, the Brits were evacuated to Crete just in time and left for Egypt afterwards. Elizabeth was clearly enjoying the adventures, appreciating both the random company of bohemian refugees and the pleasures of the Mediterranean life: the sun, the cuisine, the wine.

In Egypt Elizabeth Gwynne spent some time in Alexandria (keeping company with Durrell who later celebrated the city in his famous ‘Alexandria Quartet’), then travelled to Cairo where she parted ways with Gibson-Cowan and immediately married Lieutenant-Colonel Tony David. Eight months later, the lieutenant colonel was posted to serve in India, leaving his wife behind to work at the local branch of the British Ministry of Information. It would seem that this is where their marriage came to an end. Nevertheless, Elizabeth Gwynne transformed into Mrs David.

For several years she led the strange existence shared by the European exiles in North Africa at the time: for a more detailed depiction of their lifestyle, see ‘Casablanca’ and ‘The Alexandria Quartet’. She changed lovers, had fun, read a lot and learnt a lot – not quite the things she had been taught at the Sorbonne. The Mediterranean with its colours, flavours and smells became her passion – which is what made it so unbearable in 1946 to return to the grey London, half destroyed by the German bombs, with its ration cards and the ubiquitous Protestant smell of boiled cabbage. It was then that David launched her culinary revolution.

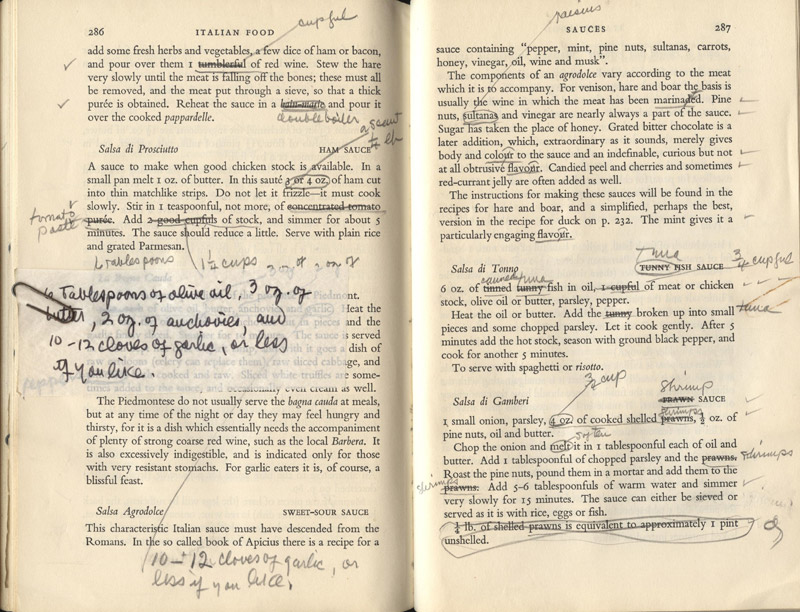

There are few things in the world that can equal the gloom and sadness of the English kitchen as it was formed in the 18th century – with the possible exception of the Irish cooking derivate from it (with the exception of the breakfasts!). Boiled cabbage, carrots, potatoes; meat stew – in the best case, fish and chips from a newspaper cone – in the worst; that about describes everything that His Majesty’s subject could hope for in 1946. Again: meat, butter, eggs and some other products were strictly rationed. The rest of foodstuffs were not considered edible. Garlic was practically illegal; tomatoes were referred to as ‘poisonous berries’ since 19th century; the majority of British housewives did not even suspect the existence of aubergines. I already mentioned the status of olive oil. Elizabeth David waged her war single-handedly – and won it. Her early culinary articles were compiled and published under the title ‘A Book of Mediterranean Food’ in 1950. The book was hugely successful; five years later, it was reissued as part of the popular pocket-size Penguin Books series. David tackled the problem with extreme seriousness. She read dozens of books in different languages. She travelled in the Mediterranean: she ate, listened and cooked. She explored London’s ethnic corner shops – the only places where you could buy something other than the usual stuff available at the British butchers and greengrocers. It was not a housewife sharing her experience in tasty and thrifty cooking; it was an energetic, clever, well-educated cosmopolite opening new – and perfectly attainable – worlds to her compatriots. Her exact, laconic and flexible style could be the envy of practically any British writer of the time; in fact, there are not many who can present their subject in an interesting and clever manner to an ill-prepared reader even today. Sometimes flowers of eloquence blossom in the pages of her books; however, they are neither too plentiful nor invasive; her enumerative passages are on a par with Borgesian prose (written, incidentally, approximately around the same time): ‘The ever recurring elements in the food throughout these countries are the oil, the saffron, the garlic, the pungent local wines; the aromatic perfume of rosemary, wild marjoram and basil drying in the kitchens; the brilliance of the market stalls piled high with pimentos, aubergines, tomatoes, olives, melons, figs, and limes; the great heaps of shiny fish, silver, vermilion, or tiger-striped, and those long needle fish whose bones so mysteriously turn out to be green.’ Being an Englishwoman – and therefore a positivist and a follower of the cult of common sense – Elizabeth David did not turn her books into monuments of gastronomic experiments and silly poncery; she championed simple food, ‘vernacular’ cooking, as it were – but free of any romantic ethnography. The Protestant gloom of dinner in the average English home was not her only enemy; she also felt genuine disgust for la-di-da show-offs in the kitchen; in France, for instance, she preferred simple provincial recipes to the overrated Parisian haute cuisine: ‘It is honest cooking, too; none of the sham Grande Cuisine of the International Palace Hotel.’

Elizabeth David’s victory was overwhelming and her influence on the British life – profound. It only took a few years after the first publication of her ‘Book of Mediterranean Food’ for olive oil, garlic, Italian pasta and even aubergines to appear in London shops. David further reinforced her success with a string of books: 1951 saw the publication of ‘French Country Cooking’; it was followed in 1954 by ‘Italian Food’, in 1955 – by ‘Summer Cooking’ and in 1960 – by French Provincial Cooking. The Vogue Magazine ran her culinary columns and food travelogues which were then compiled in books with some excellent titles, like ‘An Omelette and a Glass of Wine’. In 1965, David opened her own shop in Pimlico in London. And it is, first of all, thanks to Elizabeth David that today you can choose from a number of different brands of olive oil, hummus or olives from Greece, Italy or Spain at any godforsaken branch of Tesco anywhere in Britain.

The fiercer David’s attacks on British culinary habits were, the more of a patriot she became. From 1952 to the end of her days, this cosmopolite lived in the same house in Chelsea. From the late 1960s, Elizabeth David devoted herself to the favourite pastime of educated English country squires (to which she, in fact, belonged by birth) – historical research. She compiled material for a work that was to crown her literary career – and it was dedicated to none other than English bread. Elizabeth David toiled in libraries, visited mills, bakeries and pastry shops; in the company of her friends and experts, she baked loaves of bread and cakes. The result was a 600-page volume entitled ‘English Bread and Yeast Cookery’ – a masterpiece of non-fiction literature, a treasure trove of knowledge, common sense and patriotism. It is a book about daily bread – ‘daily bread’ in every sense of the phrase: historically anthropological, practically culinary, existential, literary. Everybody knows the works of French and Italian historians of material culture; sadly, the fame of ‘English Bread’ has not transcended the boundaries of a quite small circle of informed readers.

Despite suffering a stroke at the age of 49, Elizabeth David lived a long life. Showered with awards and honorific titles, she increasingly retreated from the eyes of the media and died, aged 89. Today’s multitude of TV chefs and cookery writers have done nothing to detract from her influence.