The “Adoration of the Magi” and the Giving of Christmas Gifts

Estere Kajema

23/12/2015

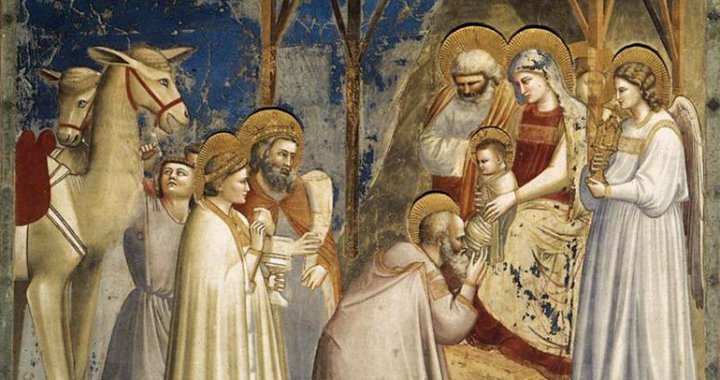

The Adoration of the Magi is a Biblical passage that mentions the three kings who travelled to witness the Nativity of Jesus and to give him three gifts – frankincense, gold and myrrh. The Birth of Christ has played a major role in the development of Western art, and even though the image of the Virgin Mary holding the Christ Child – Madonna and Child – is an especially prominent theme, this specific subject has been historically crucial for both art patronage and religious art.

There are three paintings depicting the Adoration of the Magi that really stand out with their grace and glory – “Adoration of the Magi” by Bosch, Velazquez and Botticelli.

Hieronymus Bosch, Adoration of the Magi, 1485-1500

Hieronymus Bosch, Adoration of the Magi

/ Driekoningen-drieluik (1485–1500)

Hieronymus Bosch painted his version of Adoration of the Magi at the end of the fifteenth century. His triptych depicts the scene of adoration on a central panel, whilst on the two side panels, he decided to depict the monetary patrons of the triptych and their saints – Saint Peter and Saint Agnes. The triptych has a variety of small and delicate details – scenes that the artist intentionally hid behind the main narrative of his work.

The left panel, as mentioned, depicts one of Bosch’s patrons – Peter Bronckhorst, who is praying on his knees, with Saint Peter behind him. There is a figure of a man far behind them, most likely Saint Joseph – who is known as the Workman – washing baby Jesus’ diapers. Further in the background one sees various figures of men, women and cattle.

The right panel depicts a second patron – Agnes Bosshuysse, who is also praying on her knees, with Saint Agnes standing behind her. In the background of this side panel Bosch illustrated a bear and a wolf attacking farmers, and in the very back – a beautiful lake.

The main scene of Adoration takes place in the central panel. Bosch creates a dramatic scene in which the three Kings lay their presents at the Virgin Mary’s feet. Balthazar, one of the Magi, kneels with his present before him – a golden sculpture depicting The Sacrifice of Isaac.

Gaspar, the Magus wearing white garments, is waiting to give his present to the Madonna and Christ – a pyx with myrrh inside of it. The third Magus, Melchior, wears a golden knight-like mantle. He is the King who gave Christ frankincense – a vessel containing incense.

A nude, doll-like and unrealistically petite Christ Child sits on the Madonna’s lap. The farmers and shepherds who came to greet Jesus surround the scene – they are looking out from the shed, and climbing on the roof and into the trees, to get a better view of the scene. It is obvious that Bosch has neglected the figures of the farmers and purposefully makes their appearance much less appealing than that of the Kings or the Virgin Mary. This is something that can often be seen in Christian art: the shepherds and local farmers are identified as the Jews who rejected Christ, whilst the Magi, who were non-Jews, recognized Christ as their one true Messiah.

And then Bosch presents us with a man standing in the doorway of the barn. He has a large, majestic crown on his head. He is looking straight at Jesus, with a wicked smile on his face. The men surrounding the crowned man are different than the shepherds – they all have wicked expressions, as if they all share the same malicious idea. These men are standing in a rotten, broken-down stable or shed – which often symbolizes the synagogue as an old and dying religious practice. It is widely thought that by painting the crowned man with his followers, Bosch was adding the figure of the Antichrist to the painting.

Diego Velazquez, Adoration of the Magi, 1619

Diego Velazquez, Adoration of the Magi

/ Adoración de los Reyes (1619)

Only one hundred years later, Diego Velazquez, a Spanish Baroque artist, painted a completely different version of the Adoration of the Magi. In Velazquez's painting, the distant background is vaguely lit. The artist uses the typical Baroque technique of chiaroscuro – he highlights the crucial difference between lightness and darkness in order to create a dramatic scene. It is important to note that Adoration of the Magi is an early painting of Velazquez – he was a pupil of Pacheco at the time, and the painting was done at the study studio. The artist used real people as examples and models for the painting: the Magus with a grey beard is a portrait of Pacheco, the artist’s teacher; the Virgin Mary was painted from Juana, Pacheco’s daughter; and Velazquez painted himself as one of the young Kings giving a present to the Christ Child – who here is portrayed as a calm infant, as opposed to the unnatural-looking Jesus painted by Bosch.

Indeed, Velazquez was unaware of the garments that would have been worn at the time when Christ was born, so he made the decision to give all of his characters contemporary clothing. Nevertheless, the artist managed to retain the Madonna’s holy and virginal image – full of submission and calmness. Velazquez made Jesus’ figure the brightest one in the painting – one can almost see rays of light coming from the Child’s head, like a tiny halo. The painting seems so very modern – based on the contemporary garments and the liveliness of the scene – that one almost forgets about the holiness of the subject. Considering the large scale of the canvas, it could easily be displayed in a church; yet the utter absence of spiritualism in the painting is so strong that it could also be simply portraying a regular Spanish celebration of a new infant. All of the essential attributes of the famous Biblical scene are missing – there are no feathers nor gold on the Magi’s garments; Jesus is tightly tucked in, as compared to other paintings depicting the same subject; and most importantly – there is no shed/barn. Velazquez intentionally omits all sacred meaning from the scene, leaving the spectator to make mere assumptions on what the true subject is.

Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi, 1475

Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi

/ Adorazione dei Magi (1475)

Sadro Botticelli, the Italian Renaissance painter, was, in fact, commissioned by various patrons to create for them a painting depicting the Adoration of the Magi. This particular one was commissioned by Gaspare di Zanobi del Lama, who was a member of the House of Medici and owned his own chapel in the now-destroyed church of Santa Maria Novella. Traditionally, once a master was commissioned to create a work for the Medici family, he would work portraits of the members of the family into the work. Here, for instance, Cosmo de Medici is portrayed as the King presenting a gift to the Madonna. His sons, Giovanni and Pietro, and his grandchildren, Giuliano and Lorenzo, are also present in the painting – as well as del Lama himself, of course.

Giorgio Vasari, the Italian architect, painter and writer, was most famous for his book, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. It was because of the success of this book that artists could be called “artists”, rather than “masters” or “creators”. Vasari mentions Botticelli's Adoration of the Magi in his book thusly:

"The beauty of the heads in this scene is indescribable, their attitudes all different, some full-face, some in profile, some three-quarters, some bent down, and in various other ways, whilst the expressions of the attendants, both young and old, are greatly varied, displaying the artist's perfect mastery of his profession. Sandro further clearly shows the distinction between the suites of each of the kings. It is a marvellous work in colour, design and composition."[1]

The high finish of the painting, and the grace and accuracy of Botticelli’s brush and colour palette, are stunning beyond belief. He too, as Velazquez, chose to dress the characters of the painting in contemporary garments; as well as give every person he painted a traditional Italian profile. The group is not standing by the barn; they are surrounded by the ruins of an ancient Roman temple. The Virgin Mary sits submissively, holding the Child on her lap, whilst Joseph stands in a very relaxed pose and tenderly looks at the infant Christ. As mentioned before, Botticelli placed several members of the House of Medici into the painting, but he also painted in famous poets, philosophers, writers – and himself, too.

Unholy Gifts

There is one crucial thing that unites all of the works of art mentioned above – apart from their subject, that is. All of the paintings were commissioned – none of them were created from an artistic burst of inspiration or as a religious impulse. This, in my mind, is the exact beginning of the commercial and wickedly capitalistic side of the holy celebration of Christmas.

Whilst the commissioning of paintings, altarpieces and sculptures with religious subjects or for religious purposes is, in itself, a rather questionable act of worship – Can one really buy a depiction of holiness? – the true Christmas atrocity is the act of gift giving. When the Three Magi brought presents for the Madonna and Child, their generosity was pure and divine. Yet today, it is completely different.

Have you ever thought about the fact that every year, “the Christmas season” starts increasingly earlier and earlier? It begins on Black Friday, when everybody tries to get the best deals on Christmas presents. In fact, it begins with the fake, plastic Christmas trees in shop displays – put there at the beginning of October with the sole purpose of reminding you that you must not forget to buy gifts. In a way, everything around you essentially forces you to buy gifts. Coca-Cola advertisements in the cinema, with a “the Holidays are coming...” song that will be embedded in your brain, straight from the screen. And then, on the Holiest Night of the Year, we do our best to create the so-called Christmas spirit – decorated trees, lights, gifts, tangerines, TV, music – all of which you should have bought several weeks before the celebration. Television makes us believe that the Grinch is a wicked character; yet isn’t the Grinch nothing if not a symbol for anti-consumerism?

This Christmas, let us remember that the contemporary tradition of gift giving is not the most important part of the celebration – it is fuel for the commodity-fetishism of our society. Let us hold on to the most important things we already have – our spirit, our family and our belief.

Merry Christmas!

[1] Giorgio Vasari, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects. New York: Random House Publishing Group. 2005