Lucian Freud. A Narrative of Portraiture

Estere Kajema

19/10/2015

Some know him as a grandson of Sigmund Freud, some as a great gigolo. Famously called by The Financial Times as “one of the greatest painters in history”, Lucian Freud is undoubtedly one of the most excellent and well-known British artists. He is a creator who worked in many different techniques, using various styles and methods – most famously pencil drawings and oil paintings of human bodies. Freud particularly enjoyed painting portraits. He said that anything could be a portrait and that everything deserved to have a portrait, because even furniture has its own personal biography.

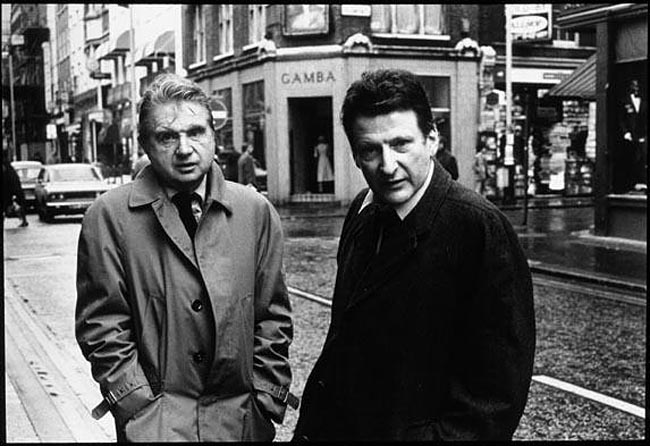

Lucian Freud was born in Berlin in 1922. His wealthy Austrian-Jewish family had deep and famous roots, and Freud’s father was Sigmund Freud’s younger son. In 1933, the family left Nazi Germany to seek safety in England. Lucian Freud started his education in art high school, and continued his education at Goldsmiths College. His early works are usually highly finished and have a smooth, perfect surface, depicting clear and sober picturesque representations. One of Freud’s closest friends, Francis Bacon, once told him that he found his style rather boring, and suggested he should make some changes in his technique – maybe add some freedom and reduce the sharpness. After that, Freud started to paint with thicker, juicier brushstrokes, concentrating on the body and bodily flaws.

Francis Bacons and Lucian Freud. 1950. Photo: Harry Diamond

For Freud, to paint a portrait does not necessarily mean painting a photo-realistic representation of a body or a face. By painting a body, Freud always paints a soul. Freud’s portraits often represent bodies that are far from the stereotypical notion of beauty. In the vast history of art, nude women – whether it is Olympia, Venus or Judith – are all proud of their bodies, their bodily homes. But here, the women, through being nude become defenseless. Lack of clothes does not suggest sexuality or desire. On the contrary – it suggests vulnerability, sadness, anxiety and loneliness of the human body, and even more – of the human soul. Freud’s subjects are never jolly. Their lives are full of tragedy, pain and traumatic memories. Their bodies have deeper histories and scars, and they always carry a deeper narrative.

Julia Kristeva, a Bulgarian-French philosopher, introduces and describes a state of abjection – subjective sentiment one experiences when seeing something that reminds them of their own corporeal memories. Abjection could in some way be translated as disgust, and it refers to personal feelings of safety and comfort. For instance, when one sees an image of some terrifying massacre, one immediately feels a deep and sickening discomfort, mostly because an image of blood and pain reminds one of his or her own blood and pain. Freud’s portraits depict disgusting, dirty bodies, which remind the spectator of their own vulnerabilities, bodily scents, and fears of being naked.

Photograph by Freud’s assistant, the painter and photographer David Dawson, capture the artist at work and provide a valuable insight into the process of painting a portrait. Courtesy of Hazlitt Holland-Hibbert

Freud’s friend (and another great fellow British artist), David Hockney, said that once when he had to pose for one of Freud’s portraits, they spent over 120 hours together. Freud would always ask him to talk and to move, so that he would see how much Hockney’s facial expressions and body language could change. Whilst painting, Freud always spoke to himself, asking questions such as “Does that look good?”; “No, this is the wrong colour”; “Should I change this?”. The artist’s style of painting is an infinite dialogue between Freud and Freud. Always trying to be the best version of himself, always trying to show the most accurate depiction of the soul, Freud would spend days and nights in front of one canvas, trying to make his work truly perfect.

In her article “Lucian Freud Drawings In the context of Freudophila”, Marina Vaizey writes that Freud was hardworking and obsessed with painting. “All accounts indicate that for most of his life, when not dining with his friends and models (often one and the same) he was working – morning, noon and night.” The artist worked quietly and passionately – having lived and worked in London for over 60 years, he produced vast numbers of paintings and drawings, which undoubtedly transformed and enlightened British post-modernism. In fact, Lucian Freud is one of the most expensive contemporary artists in the world; in 2008 his artwork Benefits Supervisor Sleeping was sold through Christie’s for $33.6 million, establishing a new world record for the highest price paid for an artwork by a living artist. The painting was bought by Roman Abramovich.

To illustrate Freud’s excessively honest and articulate depiction, I shall analyse three oil paintings created by him - Girl with a Kitten (1947), Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (2000–2001), and Kate Moss (2002). The first work, Girl with a Kitten, depicting Freud’s first wife Kathleen, was created before the artist’s famous conversation with Francis Bacon. The two other examples were painted much later, when Lucian Freud had already adopted his later signature style.

Lucian Freud. Girl with a Kitten, 1947. © The Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images

Girl with a Kitten

This portrait depicts Lucian Freud’s first wife, Kathleen Garman. It is a cropped picture of a young woman staring to her right. She is posing in front of a beige background; in her hand, Kathleen is holding a kitten by its neck. Judging from her sharp and pointy knuckles, the viewer gets the feeling that Kathleen might be harming the animal.

Kathleen, who was the eldest daughter of another famous British artist and sculptor, Jacob Epstein, was never called by her full name – her friends and relatives would simply call her “Kitty”. This really makes us ponder upon the hidden meanings of the painting. Following his famous grandfather, Lucian Freud might be telling us of Kitty’s controlling, yet really self-harming, temper.

The painting, which can now be seen at the Tate Britain in London, is one of the most intense paintings by Freud. It was done one year before the couple entered their marriage, which did not last long. It was followed by Freud’s two other marriages, numerous affairs and, famously, around forty children.

Lucian Freud. Queen Elizabeth II, 2000-2001. Photo: © Royal Collection Trust 2012/the Lucian Freud Archive

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

When Freud first introduced the infamous portrait of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, both Brits and the Queen herself found this very specific representation highly unflattering and dissatisfying. For the first time, the British Monarch was painted in such aggressively close scrutiny. Instead of showing the majesty and importance of the Queen, Freud chose to paint her on a tiny canvas. The Queen looks like an old, tired woman. Her crown, instead of symbolizing the Queen’s power, is overwhelming, thereby depicting the heaviness and difficulty of ruling the monarchy.

It is important to remember that the portrait was not commissioned. Freud gave Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II to the Queen, which means he had much more freedom of expression, and no one was holding control over his work. The Queen sat for the portrait between May 2000 and December 2001, and, as requested by Freud, she wore the famous Diamond Diadem depicted on post stamps and bank notes. Perhaps with this portrait, Freud was trying to depict the obsolescence of the monarchy and the public's familiarity with Queen Elizabeth II and the Royal Family.

Lucian Freud. Naked Portrait, 2002

Kate Moss

Towards the end of his life, Lucian Freud established a close friendship with the famous British model Kate Moss. They respected and blindly adored each other. Moss often spoke of Freud as the most interesting and intelligent person she had ever met. Apparently, the only thing that could have been an obstruction in this inspirational friendship between Moss and Freud was the fact that the model was always late for her sittings.

The well-known painting depicts Kate Moss when pregnant with her daughter. Coming back to the notion of the abject – this large canvas shows one of the most beautiful women alive, but when one looks at Kate Moss, they are in no way aroused or even slightly attracted to the depicted figure. The only way to put it down in words is to say that Freud is never depicting a human body – and never the elegance, grace or beauty that women would prefer to have. In his portraits, Freud is depicting flesh. Soiled, smelly, slightly dirty, an impossibly human flesh; something which was never painted to arouse. The painting is supposed to bring us back to our own body, and remind us of the earthiness and simplicity of our own existence.

(Fragment) David Dawson. Lucian Freud and Kate Moss in Bed, 2010. From Lucian Freud: Studio Life series

Lucian Freud passed away in 2011, when he was 89 years old. He wanted to spend his last days standing behind a canvas, working as hard as he could. Unfortunately, his body and illnesses let him down, and the artist locked himself in his house in West London. This, indeed, was a message for his friends – I am done. For the first time in over fifty years, Freud could not make himself get up and paint. After two weeks spent in bed, the artist passed away. The majestic and powerful legacy that he left behind is a pride for Britain. Freud, who undoubtedly was one of the most controversial post-modern artists, was also one of the most forceful, emotional and deepest artists in art history. Always so frightened by death and hating human mortality, Freud managed to stay immortal through his rich brushstrokes and unprecedented narratives.