Artists’ studios in Moscow: Then and Now

Anna Arutiunova

19/02/2015

Some of the brightest memories from my childhood are the visits to my grandfather’s studio. There was a flavor of mystery to them – you had to enter a regular residential building, and it seemed that no one around could guess that you were heading to the artists’ realm. But there it was – in the attic of a dwelling house, where a long corridor, with dozens of doors to your left and right, was always submerged in darkness. But once a door opened and you avidly peered into what was behind it, you saw piles of canvases, easels, unfinished sculptures, printing presses and much more.

O.A. Ponomarenko. Artist's studio. 1843

There is nothing surprising in the fact that an artist should have a studio. Indeed, from art history we are used to learning about the workshops of great artists – studios that were inseparable from the artistic being that inhabited them. Few people, though, would think about the economics behind the artistic studio, and moreover, about the way a studio might be an embodiment of the state's policy concerning the arts. Recent years have seen an avalanche of international residencies for artists, funded projects with the goal of providing artists with spaces to work in. Russia is no exception to this process, though here the newborn system of artistic residencies co-exists with a rather unique scheme of artistic atelier allotments that are overseen, to a certain extent, by the state. This scheme is one of many soviet relics that have made their way into contemporary Russia.

It might, indeed, seem unusual that the state takes responsibility for providing artists with ateliers, and almost for free. But the workshop question had never been of minor importance for artists in Russia, partly because it was an embodiment of a complicated relationship with the state. Kazimir Malevich, for instance, in his “Declaration of Artist’s Rights” written in 1918, claimed immunity for artists’ lodgings and studios, along with the sovereignty of individual life and freedom from any ideological and state structures. Since the early post-revolutionary days, fierce discussions were held about how artists should organize their working process, and how it should relate to the state and its goals.

Vladimir Pereyaslavets. The astronauts in the artist's studio. 1964

The urgency of those questions manifested itself in a proliferation of artistic unions of all kinds. In 1917, avant-garde artist and writer Ilya Zdanevich envisioned a new Union of Artistic Workers which would guarantee freedom of creativity and artistic views, denounce the state’s “patronage” over the arts, and give artists the means of control over state initiatives in the cultural sphere. That same year another union was formed – the Union of Artists-Painters of Moscow – close in its structure and goals to a trade union. Kazimir Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin, Olga Rosanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova and many other Russian avant-garde artists took active part in drawing the outlines of this new entity. It was due to them that the ideals and principles of avant-garde art – economical and spiritual emancipation from conventional art criticism, as well as from market, capital, private or state influence – were introduced into the organization. However, not everyone was happy with the emancipating aspirations of the avant-gardists; some saw the revolutionary cause in a different light. In 1922 the Association of Revolutionary Artists of Russia (ARA) was founded. Its members put forward the ideals of realism, and they saw as their goal the depiction of the lives of Red Army soldiers, workers, peasants, revolutionary activists and labor heroes. Targeting the masses and seeing revolution as a shift in the roster of themes, rather than of forms, the ARA was in clear opposition to the avant-garde, and dubbed it a “harmful invention”.

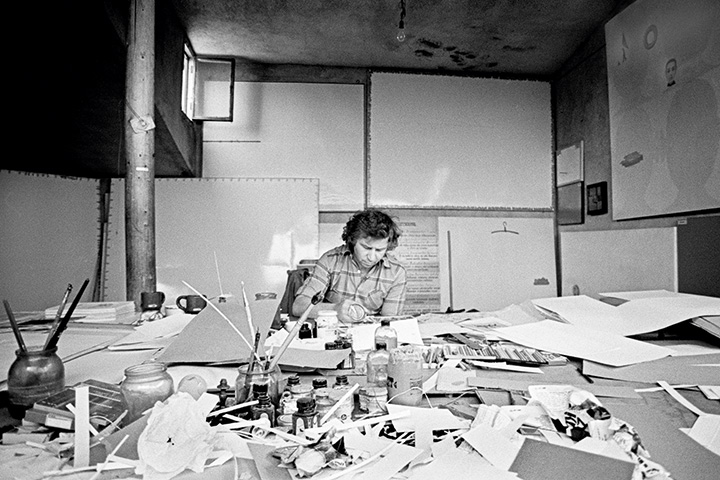

Ilya Kabakov in his workshop. 1975. Photo: Igor Palmin

By the beginning of the 1930s, the post-revolutionary multiplicity of unions was suppressed and, eventually, subjected to the centralizing intentions of the soviet regime. In 1932 the decree “About the Restructuring of Literary and Artistic Organizations” entailed the establishment of the Union of Soviet Artists. It was to be the one and only organization for creative workers in the USSR, and its main objectives were “to create ideological, highly artistic works”, “to assist in the construction of communism”, “to set the ideals of soviet patriotism and proletarian internationalism”, etc. Unified under the unwavering gaze of the state, some artists welcomed the change, while others had no choice but to acquiesce.

Membership in the Union, despite its ideological charge, was seductive as it gave artists some practical benefits. They didn’t have to go to work everyday, but were not, therefore, considered as being “social parasites” (a definition that entailed administrative and even criminal penalties). They could get free access to “doma tvorchestva” – a sort of artistic residency in the countryside. Thanks to specific “artistic trips”, they could even go abroad – a unique and almost impossible task for a regular citizen of the USSR. But most importantly, artists could get free studios because just like other, more traditional workers, they were regarded as equally responsible for the advance of socialism. They just needed their particular type of factory.

It’s worth mentioning that the system functioned not only in favor of the officially approved artists, but for underground artists as well. In 1968 Ilya Kabakov, being a member of the book-illustration section of the Union of Artists, managed to settle into a studio in the attic of a building on Sretensky Boulevard, in the very center of Moscow. It quickly became the most vibrant place for the holding of artistic discussions by the otherwise oppressed non-conformist circles. Since 1992, the former workshop of Kabakov has hosted the Institute for Contemporary Art, which still remains one of the few alternative educational centers for young and aspiring artists.

With the fall of the USSR, the majority of benefits offered by the Union disappeared, although the main attraction – a chance to have a working space, or at least to keep the one received during the soviet era – remained. There is no consensus about the relevance of this system to the artistic reality of the new Russia. The extremes of opinion go from condemnation of the Union (and consequently, of the studio allotment procedure) as a Stalinist leftover, to the admission of the fact that, for many artists, it is the only way to circumvent market-driven high rental prices.

The main problem, though, is that this system hardly embraces the younger generation of artists, especially those who are unwilling to follow the traditional academic track. Even though registering with the Union is not complicated, the disassociation with the arts system inherited from the soviet past has turned out to be stronger. Bureaucratic complexities, long queues and the ghost of the soviet public body hovering above the Union keep younger artists from meddling with it.

One of the Elektrozavod workshops. Photo: nomerz-art.livejournal.com

The physical necessity to work, and the lack of attention to the needs of younger artists from the side of the state or private organizations, have led to a somewhat positive, albeit forced, effect. Constrained with facing rental-market prices, younger artists in Moscow started to self-organize and search for alternatives. As a result, several art clusters in which workshops play a central role have appeared in Moscow over the past three years. The most vibrant one is Elektrozavod, a genuine grassroots community that attracts recent art-school graduates, designers, architects and better-established artists. The non-functioning parts of this huge electricity factory are rented out for a relatively small amount of money.

A place once occupied by the state has now been given over to private initiatives, which are slowly picking up the slack. For several months in 2014, budget studios were being provided by the “Sokol” Arts Center, which eventually shifted its attention to exhibiting and educational activities. In the summer of 2014, “povART studios”, in the very center of Moscow, were created as part of the «Art residence» project by Konstantin Grouss. A more lasting initiative is that of Vladimir Smirnov and Konstantin Sorokin – an art foundation that, since 2011, has been providing young artists with studios for free. It’s rather difficult to get one since there are several more-or-less permanent residents, but artists can apply for a space to work on specific short-term projects.

Initiatives that support younger artists in a practical sense and help them develop their creative careers are still lacking in Moscow. The not-so-encouraging experience of the soviet system, the complexities of the current Russian economic situation, as well as the difficulties that younger artists face in their pursuit to self-organize, leave a lot of open questions. And the main issue is whether state, private or grassroots initiatives will be the ones to change the working conditions of artists in the near future.