“Street art is marred by a confusion of legal and illegal expressions...”

Jacob Stubbe Østergaard

02/06/2014

Street art is dead

Punk rock died in 1979 and street art died in 2011.

So the story goes. They conquered our hearts and then they faded away. They outlived themselves.

As for punk rock, some say it checked out when The Clash learned to play their instruments properly. The music picked up tune and thereby subscribed to musical convention, and the rebellion was over.

The death of street art has been announced numerous times. In 2011, the last article in an accomplished and complete book on Danish street art reached the conclusion that the era of street art was a bygone time in the 00's. According to the author of this article, former street artist Jan Danebod, any acts of true street art had become inextricably tangled with other artistic expressions sanctioned by law or paid for by sponsors. It was being sorted and organized by authorities that adhered to the laws - however liberal - upheld by those in power.

"Because of the narrative that's been built up around the concept of street art, this is hard to ignore.", he wrote. "As a concept, 'street art' became an emblem of something by definition progressive and uncompromising." [*] Danebod then proceeded into this scathing funeral speech:

"The whole thing is rotting, and meanwhile being kept alive on life support as a flattering, flatted-out image. Sold out but unfortunately not out of stock. Available in a discount version with no edge, no will and no character. The critical potential which has implicitly been bestowed on this kind of work in a so-called public space has been lost."[*]

Nowadays it's looking even grimmer. At the end of 2013, the popular street art blog Streetheart finally went silent, its administrators busy with a new project. Simultaneously, leading newspaper Politiken ran an article about why street art had died (apparently no longer any need to ask whether it had died...). Streetheart owner Søs Uldall-Ekman was quoted as saying: "There's isn't as much of it as previously, and it isn't hip anymore". Echoing Jan Danebod's judgement two years prior, article author Ditte Giese points the blame towards the political establishment for having embraced street art and integrated it into their system.

After reading this recent epitaph of street art, I tried to reach the website of the most famous Danish street artist, HuskMitNavn, to see if he was still active. I was left to stare at a telling "404 - Not Found" notice on the screen.

...but the streets are full of art

But then I turned off my computer and went into the streets and found this:

and this:

And it became clear to me that whatever has happened to "street art", we certainly haven't stopped expressing ourselves artistically in the public space. I also soon found out that HuskMitNavn's website was not actually dead. It had simply been struck by a temporary server error. Now it was informing me that HuskMitNavn's works have been on show in New York, San Francisco, Brussels, Stockholm, Dresden, Cologne, Linköping, Aarhus and Copenhagen. And that's just within 2013 and '14.

HuskMitNavn is not the only street artist doing very well for himself. "Papfar" is another Danish artist who started on the street and is now hitting it big (I should note that "papfar" is a slang term for "stepfather" and "HuskMitNavn" translates as "RememberMyName"). Papfar has been on exhibition in Paris and New York and many more places, had a retrospective in his honour at a major art museum in Denmark, and sells his pieces at prices outside the realm of common people.

And far away, high up in the sky, of course, Banksy has become a global phenomenon.

How, then, can it be such an accepted fact that street art is dead?

The threat of thread

In the middle of Nørrebro - a traditional gathering point for everything wild and anti-authoritarian in Copenhagen - a drawn poster of a caricatured man stabbing himself with a knife reads: "Street art is not dead, it's only sleeping...". This piece is the work of one of the most noteworthy still active street artists in Denmark: Kissmama. This artist's easily recognizable paste-ups of people with statements on their shirts have become part of the visual image of the streets of Copenhagen.

Legal Kissmama paste-ups on a metro building site wall. Copenhagen, 2014

"I can recognize this feeling that street art has played out its role by now,", Kissmama comments, "...but I think it will return. I notice lots of children and young people going to all sorts of workshops. I believe we'll see a renaissance with new talents emerging."

"In street art, it's easy to experiment. If you want to make something out of styrofoam, you just do it. But after a while, a sort of basic form or prototype is formed. And that's what I deal in."

Kissmama does not buy into the idea that street art is dead but will concede that it's 'threatened':

"The greatest threat against street art", Kissmama says, "is the threat of being swamped in knitwork and pegboards. I find yarnbombing [the act of clothing street furniture in knitwork] profoundly dull."

"Moreover, it's a threat to street art because it will turn a lot of people towards graffiti instead when street art has become too fluffy. People don't want to be associated with it. In the end, it's all about identity. If everyone associates street art with pegboards and knitwork, men in particular might not embrace it anymore."

Indeed, several big street artists, including HuskMitNavn, have given up street art in recent years and returned to their graffiti roots.

What was it that was so great about street art?

All this lamentation of the death or near-death of street art is a testament to what street art has been. It's been something special. It's been a hyper-democratic form of expression. In galleries and museums, specific groups are permitted to express themselves. On the walls of the city, no one was permitted to express themselves. Everybody was equal and every act of expression came directly from "the people". It's been a democratic art practice which has also engaged space in a way most art cannot. Street art made its surroundings into part of the artwork, as in the picture below:

Man by rail being held up by birds. Honolulu

Pieces like this one have the ability to talk to people about the places they inhabit. It makes them conscious of the characteristics of a the places. Such awareness is usually a key ingredient in the development of a rich local culture.

Street art is in the middle of where the everyday happens. People who encounter it have no time to enter a different state of mind like most people do when entering the museum or the theatre or the opera. Street art is splashed right into the middle of our real lives.

"I make street art to stir the people who pass the places where I've put my pieces", Kissmama explains. "It's difficult to make people lower their defences. But street art is a good way to stir people."

But this might be exactly why street art is not what it has been. The element of surprise is gone, and so is the unlimited equality. The surprise is gone because by now even the most prosaic among us have heard about street art. We've read about it in newspapers, seen pictures on Facebook and watched debates about it on television. When we walk into the street, we expect street art. It's part of the tapestry now.

Its unique equality is also a thing of the past - at least in Copenhagen - because the public authorities have begun to curate street art on a large scale.

Curiously, the new metro line currently being built in Copenhagen right now plays an important role in this development. It is a circle line, circling the inner city. It traverses all the interesting urban areas outside the historical city center but still central enough not to be suburban. Eighteen new stations and eighteen construction sites have resulted in eighteen long, green walls stretching all over town, encircling the building sites. The local authorities have hired artists - 'street artists' as well as graffiti artists, poets and others, to decorate these walls. While the idea of using the construction site walls as urban canvases is certainly laudable, it also means that the pure and un-edited street art of the populace is being overshadowed by curated art which exists within the normal power structures (the city council promoting art based on their own ideas and on the artists' past achievements).

No love lost between the creator of this mural and market powers. Roughly translates to "Stick your money up your ass". Copenhagen, 2014

Kissmama's characteristic slogan-shirt figures also plume one of the green metro walls at Nørrebro.

"But that's not street art", the artist points out. "I'm fine with doing legal things. But I don't consider them street art. If you take away the illegality, you take away the street art."

There are some things that cannot seem to thrive under "orderly conditions": sex, punk rock and, apparently, street art.

Street art in the institutions

"It's not street art - it's art on the street", one of the pieces at a street art exhibition in Aarhus 2008 read.

Of all the people I've read or talked to, not one has expressed the opinion that legal or institutionalized street art is the same as illegal or independent street art. The dominant view seems to be that there is street art and then there are two spin-off artforms: curated "art on the streets" and street artists' exhibition room work. Neither qualifies as "street art" because they don't live up to the criteria of being free and of engaging the public space. Curated "art on the streets" maintains the mode of expression of street art and the spatial context of the street but removes the condition which shaped this mode of expression. It's comparable to a zoo. The animals have been taken out of nature and placed together as a display to marvel at.

When an artist takes off his coat and walks through the door from the street into the exhibition room, that's different.

"They make some art for the streets and some for the galleries", Lasse Korsemann Horne comments. He is the editor of the book "Dansk Gadekunst" ("Danish Street Art")(2011), which comprises journalistic and academic articles about street art from every conceivable angle as well as ample illustration and interviews with more than thirty artists.

"On the street, it has to be more accessible and it requires this certain aesthetics of decay", he explains. "...Whether it's a poster or something they've painted on a piece of wood, it becomes real cool only when it's been left to decay for a while. But they'll make something completely different for the galleries. I think very few have had any success simply taking their graffiti indoors. Art usually works best when it takes its context into account."

Gallerist and owner of the influential V1 Gallery, Jesper Elg, chimes in: "In my opinion, street art has never moved into the institutional space. Artists move. One day they work in the public space and the next day they use a canvas."[*]

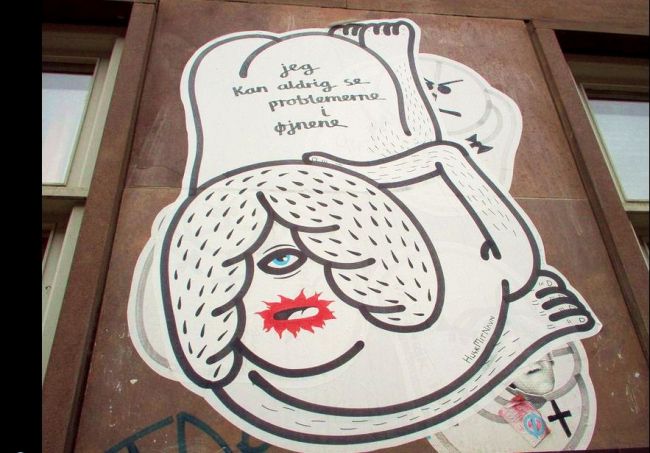

Classic HuskMitNavn street art from Copenhagen 2005. Text translates to: "I can never look problems in the eye". Photo: Asbjørn Sørensen Poulsen

So "street artists" making exhibitions in galleries and museums is really just a case of talented artists moving on and exploring new modes of expression. This explains why the lingering success of Papfar and HuskMitNavn does not sign a new lease of life for Danish street art. In this light, the idea of street art as a valuable commodity also seems absurd. It's simply impossible to buy street art because the moment you buy it, it stops being street art. The undeniably stratospheric prices of some works of street art owes largely to mythology. It reminds me of the old catholic tradition of churches owning a piece of the true cross on which Jesus was crucified. This "piece of the true cross" is just a piece of wood. The cross is missing and Jesus is missing. But the mythology of Jesus is present in the unsuspecting piece of wood. The value of this relic rests on several shaky foundations: It only has value as long as people believe in Jesus, as long as they believe this piece of wood really comes from the true cross and as long as they believe the cross' past physical closeness to the saviour is of some significance. At least one of these foundations has eroded by now and the tradition is long gone.

Reproduction. Copenhagen, 2014

The same might easily happen to street art. A traded piece of street art is an incomplete work of art. The city space made up the remaining part. The value of this fragment may rely in part on the artist's reputation, but it also relies on the mythology of "street art" as such. And the glow from this mythology will fade if street art ceases to be a subversive force. Nor will street artists be able to reach the same level of stardom even if they are very talented.

So, what is this stuff on the street that looks just like street art?

What about this "post street art" that we see on the streets today? This illegitimate heir of the true street art of old. Is it blasphemy if we take an interest in this "discount" artform?

Kissmama describes "Copenhagen style" street art as character driven, humouristic and statement-based. Below is a piece by Blød Lykke ("Soft Happiness") which is still there as I write this.

"More love would be better". Blød Lykke, Copenhagen 2014

It's soft, feminine and made of thread, but it's not without a statement. The 'grandmother' style brocade taps into a popular theme of street art: the city dweller's longing for the un-urban: nature, tradition and close, long-lasting relations. It communicates with its immediate context by contrasting it (the busy Nørrebrogade where thousands of bicycles rush by at rush hour). Brocade is a symbol of patience, and the birds on the still-standing leaves also signify peace. This piece contains Kissmama's three characteristics of Copenhagen style street art. There is humour in the words. The birds say "pip", which is the standard bird sound in Danish, but one of them seems to be saying something in human English. "More love would be better.", it says. A very moderated statement with more words than necessary. Not to be expected from a bird whose friend just said "pip". It's a polite request contrasting the bombastic street language of graffiti. The piece is signed by the artist and the style is easily recognizable. Her pieces supplement each other and enter into a greater dialogue with the works of other characters.

Pieces like this are far removed from the graffiti culture that was the cradle of street art. It's not likely to bother anyone or to upset the law, nor does it make a societal or political point. It is, however, site-specific, unofficial and meaningful.

When I asked Lasse Horne about the future of street art, I was surprised that he was not totally pessimistic:

"It all depends on the political currents.", he said. "Formerly, we had the 'broken window' policy. Smashed windows and graffiti were the two things that made people feel the most unsafe in a neighbourhood. They were the omens of an area turning into a slum. This has nearly been reversed. Now, if you want to make a neighbourhood hip, you've got to send out a team of creatives including graffiti writers and street artists first. People find an area more 'urban', in a desirable way, if there's some graffiti and street art around."

And in conclusion he added: "It's a constant play between the various agents acting upon the streets - quite an unruly and indefinable entity - and the governing political tendencies in the city at a given time."

Perhaps when we're done mourning the dramatic rise and fall of the radical expression we knew as "street art" for a fleeting and glorious moment in the 00's, we can breathe a sigh of relief. Maybe then we can start enjoying "art on the street" for what it is instead of analyzing it in the light of the past. Maybe this is really just the beginning of street art.

Cultural and political movements may die out, but not artforms. Artforms don't die. They settle.

Believers in the mortality of artforms must answer these two questions:

If punk rock died in 1979, then what is this?

And if street art died in 2011, what is this?

Drawing and stickers, Copenhagen 2014"

[*] Quotes taken with permission from Dansk Gadekunst (2011), by Lasse Korsemann Horne (ed.). Copyrighted by Lasse Korsemann Horne and the respective authors.