“How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Vandalism”

A Brief Introduction to Graffiti culture in Stockholm

Isis Marina Graham

30/05/2014

Photos: Isis Marina Graham

“Stop thinking about artworks as objects, and start thinking about them as triggers for experiences... That solves a lot of problems: we don’t have to argue whether photographs are art, or whether performances are art, or whether Carl Andre’s bricks or Andrew Serranos’s piss or Little Richard’s ‘Long Tall Sally’ are art, because we say, ‘Art is something that happens, a process, not a quality, and all sorts of things can make it happen.’ … [W]hat makes a work of art ‘good’ for you is not something that is already ‘inside’ it, but something that happens inside you — so the value of the work lies in the degree to which it can help you have the kind of experience that you call art.”

/Brian Eno/

A controversial installation by Thomas Bratzke at Kulthurhuset’s 2012 exhibition, “Street Smart”

“It’s so… clean,” one of my American friends repeatedly observed as we walked through central Stockholm on a recent visit. He was right. Stockholm is clean; it’s almost too clean, Pleasantville clean. Part of the reason for Stockholm’s squeaky-clean exterior is the city’s nolltolerans (zero-tolerance) policy towards graffiti. What this policy generally boils down to, when most people explain it, is that the city of Stockholm removes all graffiti within 24 hours of being identified. However, the policy is far more complicated than this basic one-liner, as graffiti writer and PhD candidate at Stockholm University’s Art History Department, Jacob Kimvall, explores in his book, Nolltolerans: Kampen Mot Grafitti, and summarizes in his article, Scandanavian Zero Tollerance on Grafitti. In the article, Kimvall argues that there are four cornerstones of Scandinavian Zero Tolerance:

*Removal: Zero Tolerance is based on the idea that both public and private real-estate owners are investing more financial resources to remove graffiti. The vision is a completely graffiti-free public space, since the Zero Tolerance policy argues that graffiti is ugly and creates a feeling of insecurity. In addition, it is argued that the fast and effective removal of graffiti – which renders it almost invisible in the public domain – will result in graffiti writers getting tired of constant re-painting, and they will eventually stop all together.

*Legislation: Zero Tolerance increases efforts to prosecute suspected graffiti ‘vandals’, and results in stricter legislation. Tougher legislation has, among other things, meant an increase in the maximum penalty for a normal degree of vandalism. The police have implemented a special penalty code for ‘criminal damage by graffiti’, and have the right to conduct body searches of citizens for pens and spray paint. Importantly, these are legitimated under the rubric of ‘preventative’ purposes and can be conducted without the suspicion of any crime being committed…This type of policing, therefore, operates on the edge of – and sometimes outside of – the law.

*Prohibition: Zero Tolerance is trying to ban legal graffiti in the form of exhibitions at so-called free, open, or legal walls (open to the public to paint on). Zero Tolerance is also trying to ban the production of permanent graffiti murals as artworks in the public realm. It is this last aspect – graffiti murals in the public realm – that caused the most controversy and created more problems for both proponents of and opponents of Zero Tolerance…A critical analysis of this tendency to prohibit graffiti is that without legitimate opportunities, the graffiti (and graffiti writers) are completely at the mercy of police and the anti-graffiti campaigns’ definitions of problems and perspectives. With this point [Kimvall is] approaching the last and most important aspect of Zero Tolerance, one that all the other parts depend upon: the propaganda.

*Propaganda: At first, [Kimvall] was very reluctant to use this word – because of its strong negative connotations. But after trying out alternatives, [he] found that it is the most appropriate term. Zero Tolerance in Scandinavia is built on propaganda in the sense of ‘distribution of selected information, used to promote a certain point of view’…There was a foundation laid that systematically sought to influence citizen’s opinions and actions in such a way that the increased regulation described above would appear not only possible, but also a reasonable way to solve the perceived problems that they wanted to fix This foundation was laid using rhetoric that constantly linked graffiti writing to violence, crime and drug abuse.”[1]

As hard as Zero Tolerance is trying to fight graffiti, it can easily be argued that these four cornerstones reinforce and affirm the precise culture that they are trying to prevent. Are political and cultural subversion, fighting against authority, and the ego of who will be the most bold and throw up pieces with the highest frequency and in difficult-to-access areas, not part of the thrill and appeal for many of the people who write graffiti? When a large graffiti piece appears inside an inner-city subway station, crowds gather and Instagram is filled with pictures of the piece, questioning how long it will last.

Graffiti at the Universitetet Station, 2013. “Cunt Club” and “Sorry att vi fuckade de mansliga rättigheterna / Reva” (Sorry that we fucked with human rights / Reva)

In addition to this, Zero Tolerance argues that when a person is in an area where graffiti is present, they feel insecure because it gives the impression that security or police do not patrol the area. However, this aspect of the policy is somewhat of a “catch 22”, because in Stockholm there are central areas where graffiti is removed immediately, and suburban areas where graffiti remains in place for a long period of time, and Zero Tolerance reinforces the feeling of insecurity in these areas where the graffiti is not quickly removed.

Graffiti around the city. Paint it black, 2013

Graffiti around the city. Bitch Please, 2012

Graffiti around the city. Fame, HSK, TIRSS, Crip, Diges, and other writers

Tags and Throws, Bombing Alone

In addition, Zero Tolerance is making an evaluation of the artistic quality of a specific visual style of graffiti, and as Kimvall argues, it is influencing the public perception of graffiti style, or anything made with a spray-can, through propaganda. And let’s face it – while the “what is art?” debate can, at times, result in some semi-interesting philosophical reflections, the yells and screams of “graffiti is not art” feel somewhat old-fashioned and worn. Yes, you can break graphic vandalism into various sub-categories, such as scribbles, tags, multicolor pieces, and street art – some of which have no intention, some of which have political intention, and some of which have artistic intention – but it doesn’t seem to me that anyone has the right to make a sweeping generalization around the artistic merit of something that many people do, in fact, accept and experience as art.

A well-known wall, or “fame”, in Bromma, 2014. Various writers

Koas Interview on Highlights TV (Be sure to turn on the English subtitles by clicking the “captions” button on the bottom right of the video)

“Street art” – which can be somewhat defined as having a more direct artistic or political agenda, and which is generally more aesthetically pleasing to the populous – has fallen through the cracks when it comes to removal, as well as in terms of public and institutional perception and acceptance – and this sends mixed messages.

Graffiti and street art intermingling in the inner city, 2014. Various writers

Graffiti and street art intermingling in the inner city, 2014. Spacey

Installation of Akay’s Robo-Rainbow at Kulturhuset’s 2012 exhibition, “Street Smart”

Installation by Petter Odevall and Ossian Ekerman at the Clarion Hotel 2012 exhibition, “Snabba Linjer”

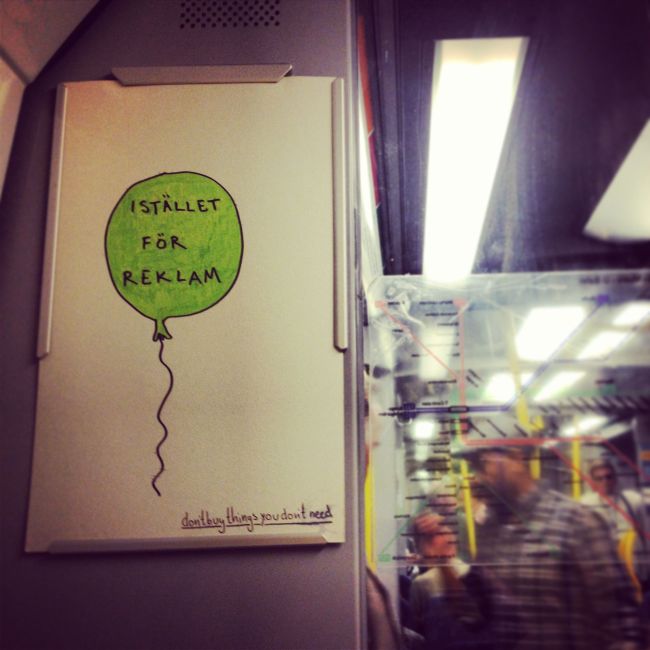

And while there is a crackdown on legal graffiti walls and resources, Stockholm celebrates public art as a source of national pride, often boasting about the subway being the “World’s Longest Art Museum”. As hard as SL, Stockholm’s public transport system, is working against graffiti in the public eye, it is very willing to sell its space to those who can afford it. Ads are a daily part of a commuter's day, and at times the ad campaigns are literally plastered on every available surface in a station or on the train, causing some street and graffiti artists to cite “reclaiming of the public space” as one of their motivations for action.

Advertisements at Östermalmstorg, 2013

Subway ads are sometimes removed and replaced by street art

Little do many people know that the non-public space within Stockholm’s subway tunnels is an underground treasure trove of Stockholm graffiti history. Generations of graffiti writers have mastered the art of exploring Stockholm’s tunnel network, and they have left their mark along the way. Because these works never meet the public eye, this graffiti from decades past remains untouched.

Kobra, Graffiti i underjorden. This video is in Swedish, but still gives an incredible visual sense of this underground network

Stockholm’s hate/hate, love/hate relationship with graphic vandalism is anything but boring; through its institutional policies, Stockholm has situated itself in a myth-like scenario – the city versus the vandals – thereby making it a fascinating city to study when debating the merits and weaknesses of anti-vandalism policies, understanding the range of thinking surrounding the topic, and examining the subculture surrounding the street artists and graffiti writers that are active in town. The history written and preserved in Stockholm’s underground tunnel system, as well as that which is written and erased, over and over again, in Stockholm’s public spaces, is an issue that warrants investigation, curiosity, and openness. Consequently, this summer I will present a summer-series of articles on this issue – ranging from photo essays and interviews, to a more in-depth history of Stockholm graffiti culture and its pl players throughout the decades.

[1] Kimvall, Jacob, ”Scandinavian Zero Tolerance on Graffiti”, pg. 106-108, Kontrolle öffentlicher Räume. 2013