Can We Talk About This?

Alise Tīfentāle

01/03/2013

Artists mostly worry about the same things that everybody else does, and in their works, they express either their own, or their clients' (or their audience's) worries. Since the appearance of Freud, who politely explained that all people really worry only about two things – sex and death, discussing art has also become much easier, and sometimes, even more interesting. This time – a short excursion to an imagined museum of world art, with the goal of studying how artists in various time periods have addressed this Freudian “death drive”.

The trip begins with the most ancient works of art ever discovered – cave drawings, which often portray either real or ritual hunting scenes. Without a doubt, death is the central motif here – sparing the hunter from it, but wishing it upon the prey. Which is why we can say that the history of world art began not with some sort of searches for the aesthetic, or with the wish to express one's creativity (that will come, eventually), but rather with the awareness of the inevitability of death, and the wish to influence it.

When speaking about the culture of ancient Egypt, it is usually stressed that it was ruled by a cult of death and the dead. The pyramids of Giza, built more than 2000 years BCE, are nothing more than gigantic tombstones – or just as likely, monuments to the fear of death. At the same time, it can also be said that in this culture, death was successfully neutralized. The unimaginable effort and creative imagination that was devoted to making the fact of human death (or, more precisely, the death of the pharaoh) harmless and something to be controlled, is a testament of surprising optimism. The body of the deceased was entombed and equipped with everything necessary so that, upon entering the kingdom of Osiris, he would not have to experience a surprising and unpleasant decrease in living standards.

Terracotta Army

Another indicative example is the creator of the ancient Chinese Empire, the first Emperor, Qin Shi Huang (circa 259 BCE – 210 BCE), who had the very human yearning of achieving eternal youth. He financed naval expeditions to find the Island of Immortality, which was mentioned in Daoist legends; from these islands, his scientists were to bring back an elixir that would ensure eternal youth. According to the story, the expedition discovered the islands that are now known as Japan, but their inhabitants were not immortal, and the scientists had to come up with various excuses as to why they didn't bring the elixir back. The Emperor was deeply disappointed, and thereby became even more concerned about his afterlife; it was his command to build the amazing so-called Terracotta Army – hundreds of figures of soldiers in full battle dress, with individualistic facial features. The underground palace that these soldiers guard, and which is yet to be fully examined, contains a miniature world, with wonderfully beautiful vistas created along the banks of a river of mercury – and all to please the immortal emperor.

In the culture of ancient Greece, the attitude towards death became more practical – in literature and art, the fact of death acquired a didactic and moralizing definition, entwined in a long and winding web of natural laws. Death can be an educational act of valor, a punishment or a fateful conclusion; and every death has its own meaning – one for Achilles, a different one for Laocoön. The presence of death was pointed out in tragedies and comedies, as well as in daily objects. For instance, one of the most notable examples of red-figure pottery – the Euphronios krater/wine vessel (ca. 515 BCE) – depicts the death of Sarpedon. The athletic and handsome hero, although sadly deceased, is honorably transported from the battlefield in the hands of the twin brothers Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death), to the care of Hermes, god of transition and boundaries.

In early Christian culture, Christ was often depicted as the Good Shepard, but the appearance of the Gero Crucifix, in the 10th century, started the long and colorful Western art tradition of depicting Christ dying on the cross. I must mention one of the highest achievers in this genre – Matthias Grünewald's 16th century painted Isenheim Altarpiece. With this piece, Grünewald surpassed all other artists with his illustrations of monstrous bodily torture and the resultingly horrible death. Taking into consideration that the patron of the altarpiece was a monastery noted for caring for the sick, one can understand the artist's attempt at depicting a suffering and death worse than that experienced by the monastery's inhabitants, and which would also illustrate Christ's empathy with the poor souls that were sick and dying.

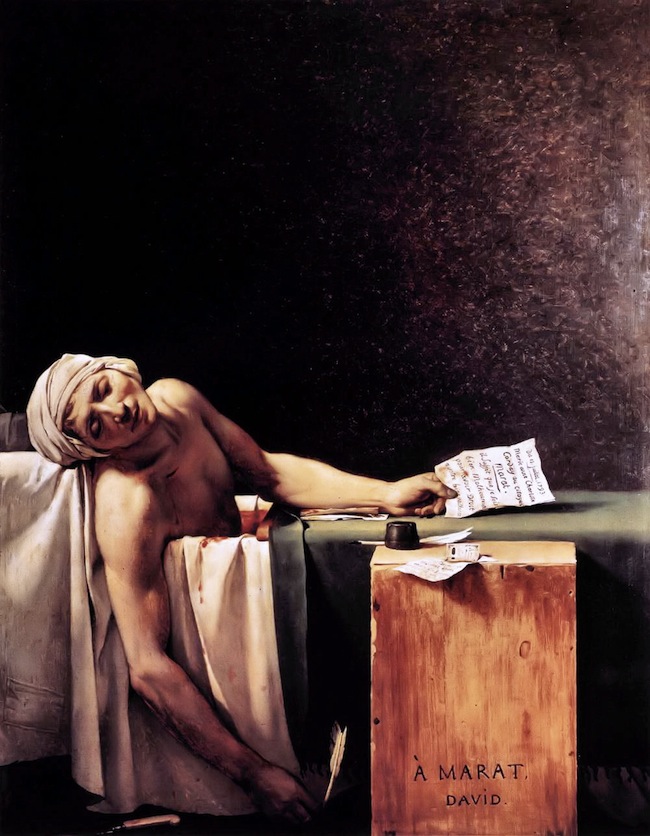

Jacques-Louis David. The Death of Marat. 1793

Skipping over countless overly-detailed and literal portrayals of the heinous deaths of Christian saints and martyrs (which had became popular during the conditions of Counter-Reformation), I'll mention just one piece created in the context of Catholic doctrine – Peter Paul Rubens' “The Raising of the Cross". The message of this masterpiece of seventeenth century Baroque painting is, of course, death. Without a doubt, the viewer must assess the work's chiaroscuro – so characteristic of the Baroque era – as well as the theatricality and emotional tension therein. At the same time, one should also note the mountains of muscles on view – their strategic placement creates a dynamic composition and, at the same time (at least for the modern viewer), adds an athletic aura to the otherwise religious scene. Death, as everything else in the Baroque era, is theater – a staggering performance – and that is how Rubens depicted it.

At some point in European history, this series of eloquent interpretation of Christ's death breaks – perhaps most strongly during the Age of Enlightenment, when the last veil of secrecy is removed from death, just like it had been for life. At least, in theory. In practice, death is nowhere to be seen; death being the absolute "end" to brutality, however, is harder to believe in than purgatory, and the artists continue to reflect on death – but in a new light.

A typical example of this new attitude towards death is "Death of Marat" (1793), by the French neoclassical painter, Jacques-Louis David. One of my most vivid childhood memories is associated with studying the "Death of Marat" reproduction in a large art history volume found in our home library. At the time, Marat and his death were the least interesting part to me – the fascinating element was the bathtub itself. Which was reasonable, since this sort of bathing tradition was not practiced in my home, and so it was the depiction of the bathtub and its rich draperies that captured my attention. What would it be like to write letters while taking a bath? It turns out that I was in the right – even art historians, when discussing “Death of Marat", point out the bathtub. A sign of the new era – an honored hero of the French Revolution has died a martyr's death, but instead of supernatural glorification, the artist chose to depict the fact of death in all its prosaic simplicity. The hero has died not in the battlefield, but at home, in the bathtub (taking an herbal bath, at that), so as to heal his sickly body. Consequently, the hero is not only physically inferior, he is even much weaker than most people. In addition, he was struck down with a pen in hand, instead of, say, a flag or a gun.

The last romantic residue left clinging to the fact of death was stripped away by Francisco Goya's painting, "The Third of May 1808" (1814). In the distance – a village, in the foreground – an execution. The soldiers – anonymous, uniformed and in formation – carry out the command, that is, "they do their job", which is to shoot people. Goya's painting is considered to be a colorful characterization of the brutality and anonymity of "modern" warfare.

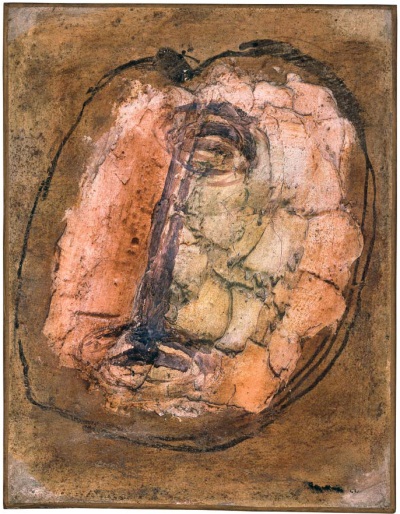

Fautrier, Jean (1898-1964) 1944 Hostage Head No. 1

The first half of the twentieth century, with its two World Wars, was saturated with death. It can be said that the fact of death was largely left to be documented by photography. But how can an artist talk about something about which it is impossible to speak or even think of? How to portray that which is not even possible to be thought about? An illustrative example of how art addressed the theme of the Holocaust is the French painter Jean Fautrier's series of paintings, titled "Hostages" (1943-1945). The series of paintings are based on Fautrier's experiences – while hiding from Nazi persecution in the French countryside, he heard a Jewish execution taking place in the woods. The key word is "heard" – he was not an eyewitness, he did not see anything; but to hear, and not see, makes it all the more tragic. In the "Hostage" series, Fautrier used brush strokes overfull with paint, and an unnatural, physiologically repugnant color palette to depict semi-abstract forms which, quite alarmingly, resemble human flesh and violently severed body parts.

I should also mention the proposed memorial project for the Auschwitz concentration camp (1958), by German artist Joseph Beuys . Although Beuys is considered a cult figure in western art, at the same time, this unrealized proposal reminds us of the sometimes overly close relationship between art and life. Here one should recall that Beuys had volunteered for service in the army of Nazi Germany. Surprisingly, Beuys turned his career as a Luftwaffe pilot (which, for most people, was not a good thing to have on your record after the war) inside out – like a glove; he made the experience a cornerstone of his successful career. Boise managed, paradoxically, to garner audience sympathy, and even admiration, with his story about the exploits of the aggressors – Nazi soldiers.

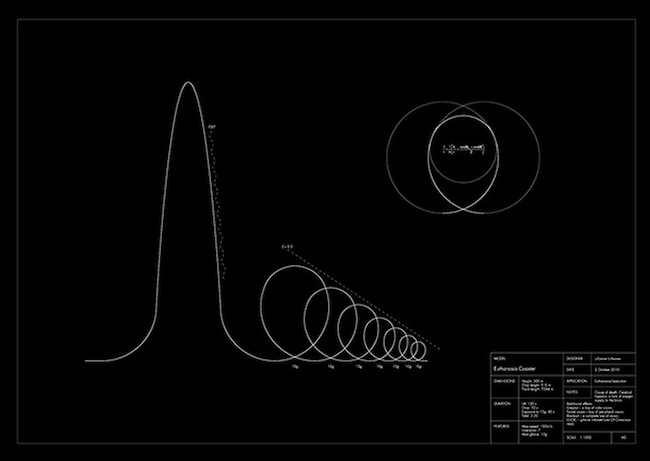

At the close of this excursion, I would like to focus on a piece of modern art – “Euthanasia Coaster” (2010), by the young Lithuanian artist, Julijonas Urbonas. In this project, a roller coaster-type of structure has been modified for the purpose of killing its riders – as an alternative to euthanasia or other methods of capital punishment. The whole principle is simply based on the laws of physics – Urbonas has calculated the relationships between speed and the force of gravity, and his roller-coaster loops (in theory) first bring the passengers to a state of euphoria, and then they snuff out their lives. Without a doubt, the artist is well aware of the speculative nature of his work (the accuracy of his calculations, obviously, cannot be verified), as well as of the fact that the project is clearly controversial and provocative. And this can only be positive, as it causes us to think and talk about it, and a discussion on death is really a discussion about life. And art.