Q&A with Magdalena Moskalewicz, curator of “The Travellers” at Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn

Q&A with Magdalena Moskalewicz, curator of “The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe” at Kumu Art Museum in Tallin

05/11/2017

“The Travellers”, a project by Polish curator Magdalena Moskalewicz, looks back on the revolution of 1989/1991 and the fall of the Iron Curtain and how this shaped the experience of traveling for the citizens of the former Eastern Bloc. Works by more than twenty artists take the viewer on a journey through different aspects of mobility during the uprising of the new post-socialist identity, from a family vacation and fancy voyages, to personal stories about closed borders during the Cold War-era and migration. “Today, we see how that moment was as pivotal for modern European history as it was exceptional. Europe’s response to foreign refugees shows that our participation in the global exchange was, and is, predominantly one-way,” states the press release for the exhibition. Previously shown at the Zachęta – National Gallery of Art in Warsaw (May-August 2016), “The Travellers” is now on view at the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn. The exhibition is accompanied by a book of the same title (published by Lugemik and designed by Stuudio Stuudio), with contributions from the artists and the curator.

Can you tell me first a bit about how the idea for the exhibition “The Travellers” came about?

This exhibition grew very organically from my previous project “Halka/Haiti”, which I curated for The Polish Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale; that film is also included in “The Travellers”. In a way, the idea for “The Travellers” came with the very many experiences that I brought with myself from Haiti and from this extraordinary project of working between Poland, New York and Haiti, namely, adapting the Polish national opera “Halka”, by Stanislaw Moniuszko, to a post-colonial context and staging it in the mountains of Cazale, the region of Haiti inhabited by the descendants of Polish soldiers who fought in the Haitian revolution in the early nineteenth century. I conducted a lot of research on post-colonial studies for this project, which then led me to think about our post-socialist condition. This was something that I hadn’t really given much thought to in critical or scholarly terms, even though I did personally experience it since I was born in Poland in the early nineteen-eighties. The confluence between the post-socialist and the post-colonial really became very alive and very present to me as I was working on “Halka/Haiti”. I wanted to take it further, in an exhibition that would focus specifically on today’s Central and Eastern Europe.

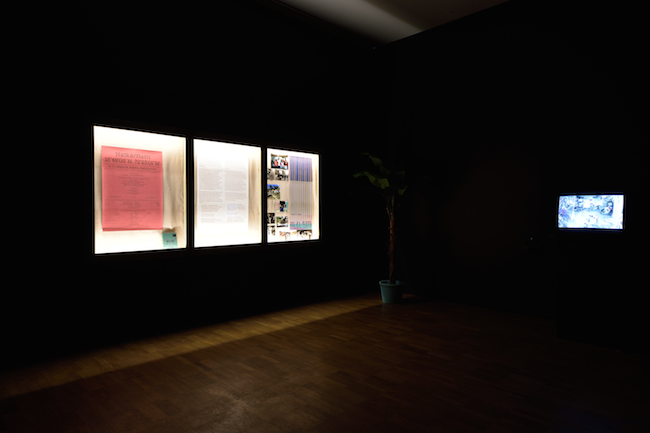

“The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe” at Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn. Installation shot with 15 Polish Painters, 1961, 2015, in collaboration with Porter McCray. Photo by Stanislav Stepashko

How do you see the juxtaposition between post-colonial and post-communist countries? What does it mean to you?

I am interested in the creation of a new society after a period of occupation, to say very broadly. How individuals organize their society after they regain independence, and how they think about that independence. I now live in the United States, and it is interesting to see how society works in a country where there has been no major revolution since the late eighteenth century – a country where there is a very clear continuity of institutions, of certain traditions of government and the organization of society. I think that my living in the United States since 2012 has made me more aware of the rupture that took place in Central and Eastern Europe between 1989 and 1991, and how defining this experience was for a whole generation of people who had lived through socialism.

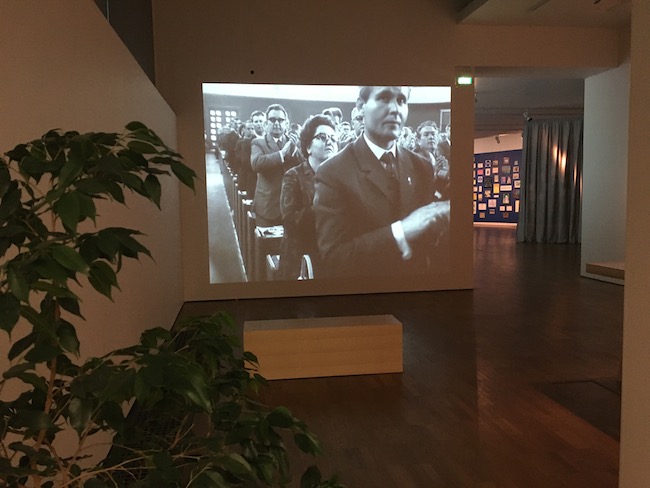

“The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe” at Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn. Installation shot with C.T. Jasper and Joanna Malinowska's Halka/Haiti 18°48'05''N 72°23'01''W, 2015 (fragment). Photo by Stanislav Stepashko

Being able to recreate your own country is an extraordinary moment, but of course, it also comes with challenges concerning how you will now define your identity within the new post-Cold War World. This, in a way, is similar to the situation of post-colonial nations as they were gaining independence. Of course, there is a big difference that cannot be overstated between the experience of colonial occupation by an overseas empire that completely eradicates your people, culture and language, and the experience of being occupied by your neighbor – an empire that is culturally similar and geographically close.

I am not trying to equalize the colonial and the socialist situations in any way. What is characteristic to both, however, is the current experience of past occupation. Remaking yourself as a society from this past occupation, according to values that you consider your own, is something that makes the post-colonial and post-socialist conditions somewhat comparable. This, of course, is not an idea that I came up with, but a topic about which many thinkers have written fascinating texts.

“The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe” at Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn. Installation shot with Taus Makhacheva's Types du Caucase, 2013 to the present (fragment). Photo by Helen Melesk

It made me also think about the connection between being excluded from society and being an artist. Even today, if you are an artist, that doesn’t mean that you are free – you need to struggle with visa problems, racial issues, and all these things. These days, an artist (or a curator, art writer, etc.) travels abroad to realize a commissioned project, to take part in a residency, or just for inspiration, and this sometimes makes one feel as if one is a refugee from one’s own country. Often times, the profession is still not treated seriously. I may be exaggerating, but I would say that not much has changed in that sense.

I don’t think that artists or art workers should have any special privileges in society. We share with other people this condition of “exile”. Something that formed the foundation of my thinking regarding “The Travellers” was reading Edward Said’s beautiful essay “Reflections on Exile” (1984). In it, Said speaks of exiles as people who have left their country of origin not necessarily for political reasons, but also for financial reasons or just of their own volition – people who ultimately find themselves and have to make their life in a foreign country, with a foreign language and a new cultural horizon. Said actually ties this phenomenon to the emergence of nationalism. He explains very powerfully how nationalism can come from estrangement, from being away from your country, your familiar habitat and your own cultural horizon. And just like with the Derridean “pharmakon”, in which the poison can constitute the cure, it is in the very condition of exile that Said sees the cure for nationalism. According to Said, an exile is given the gift of multiple viewpoints. The exile is aware of different cultural standards and, therefore, can see more clearly the threat of nationalism, whereas people settled in countries with very homogeneous cultures, languages and religions might not be able to notice it. I found this reflection on the figure of the exile as a guiding light for “The Travellers”. I did not want to call the show “The Exiles” because the common meaning of the word is different, and ultimately, it was intended as a summer exhibition at the National Gallery in Warsaw. I very much had it in mind as a show for a broad audience. But under this guise of being a relatively light summer exhibition about traveling – something that we all experience, both artists and non-artists alike – I was really trying to touch upon this very severe issue which we all should be thinking about today, and especially in Central and Eastern Europe.

“The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe” at Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn. Installation shot with Flo Kasearu's Two People by the Beach, Nothing Else, 2017 and Irina Korina's, Polish Vacation, 2016. Photo by Magdalena Moskalewicz

When you speak about exile, and how one’s nationality influences one’s perception of other countries, this logically leads me to think about the subject of artists and traveling. Artists go abroad for residencies, foreign artists are commissioned to make works because of their different points of view and perception as compared to the locals, and so on. Who is “the artist traveler”? Why do artists travel, and how is it reflected in their work?

I have to stress that the exhibition is not only about artists traveling; it is about traveling as such. But there is a strong section about artists’ travels that touches on the contemporary situation. All of the artworks in the show were made after the year 2000, but they also reflect on artists traveling in the past. There is a spectrum of possibilities in terms of how to address the topic, and I do it by looking at several things: travels related both to existential needs and the demands of the art market; exhibition tours during the Cold War; and visualizing artists’ legal struggles with migration. In terms of artist residencies specifically, it is important to notice the tension between the artist’s eagerness to travel in order to open their perspectives for the improvement and enrichment of their work, and something that I would call the imperative of mobility in our highly globalized world. Many international artist residencies are created for profit and/or to attract relatively cheap artistic labor for the neo-liberal goal of beautifying particular neighborhoods, often with very little regard to what it is that the communities actually need. There is a great piece in “The Travellers” by Wojciech Gliewicz, a Polish-American artist who has attended many art residencies on five continents. He made this beautiful, humorous movie about how he paints the same painting in different places, landscapes and cityscapes around the globe. Wojciech also told me that the more he goes to these different places and becomes aware of all these shortcomings, the more critical he grows of them. I think that artist residencies pose a threat of instrumentalizing natural artistic eagerness for novelty and inspiration.

“The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe” at Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn, installation shot. From the left: Tímea Anita Oravecz, Time Lost, 2007-2015; Adela Babanova, Return to Adriaport, 2013; Radek Szlaga and Honza Zamojski's Transatlantic, 2012 (reconstruction 2016); Wojciech Gilewicz, Painter’s Painting, 2016. Photo by Magdalena Moskalewicz

Today we can travel more freely, a fact that has also contributed to the rise of so-called art tourism. People now travel to see an exhibition or a biennial, and not just to another city but to a whole different country. Within just a few hours, you can be in London, Paris or Copenhagen.

Of course, it is the confluence of the art world with the entertainment industry that we have to be aware of. Also, a number of museums brand themselves these days primarily as tourist destinations more than anything else. I do not mean to depreciate any particular art events or institutions. I believe there is value in participating in culture regardless of the incentive. But it is important to realize that trend.

I think what is interesting, especially in relation to Eastern Europe, is that over the last 25 to 27 years of the post-socialist moment, the geopolitics of the world have changed from an East – West division to a largely North – South division. We now speak about the global North and the global South. The citizens of Eastern Europe have now joined the citizens of the global North in their travels to the global South. Shortly before and after the Iron Curtain fell, we were the ones being visited; but now we join these Germans, Americans, and Brits traveling to the countries of Africa, Latin America or South Asia. In this way, we’re repeating both the spectacle of gazing and the state of economic dependence that was specific to the colonial world, almost without realizing that we used to be on its receiving end. The particular thing with Eastern Europeans is that we see it as a kind of an improvement in our situation, but often without realizing that it is duplicating this very problematic relationship of power.

“The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe” at Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn. Installation shot with Adela Babanova's Return to Adriaport, 2013. In the background: Vesna Pavlović's, Fototeka, 2013/16 and Janek Simon's Alang Transfer, 2016. Photo by Magdalena Moskalewicz

“The Travellers” is on view in Tallinn now at the Kumu Art Museum. Estonia is a country that has experienced difficulties similar to those that Poland has gone through. Do you plan to travel with this show to Western countries as well? How do you imagine the show would be received in the United States, for instance?

As a curator, I’m always thinking about whom I am making the show for. It’s different from publishing a book or putting a piece of writing on the Internet, where anyone can read it. I see an exhibition as a temporary affair, a situation linked to the place and time in which it is being shown. This exhibition was made specifically for the Polish audience, and – as a person who has lived in Poland most of her life, went to school and worked there – I knew exactly to whom I was speaking. At the same time, having had an outsider’s perspective of Poland for more than five years now, and with the Haitian experience still very present in the back of my mind, I felt that I had things to share – about cultural differences, about a shared Eastern European identity – that aren’t necessarily obvious to every museum-going Pole. The Estonian invitation came later, and I adapted the exhibition slightly for Estonian viewers. I never thought of “The Travellers” as a show for Western European or American audiences. I would love to show a version of it here in the US, but it would definitely need to be a different exhibition; I would need to rethink it anew.

The pragmatic answer to your question is: as an independent curator, I depend on institutional invitations. This exhibition doesn’t have a traveling schedule right now; Estonia is, most likely, its last stop.

Wojciech Gilewicz, Painter’s Painting, 2016, video still

You said that you adapted the show to an Estonian audience. Can you say a bit more on what these alterations were?

The invitation to Tallinn was both flattering and challenging, since I had visited Estonia only once before. I have some Estonian friends but I wasn’t following the art scene closely, so I wanted to at least adapt the existing show to the particularities of the Estonian situation. I didn’t want “The Travellers” to be a product that can be shown anywhere and always look the same. Estonia is also a post-socialist country, so the similarities are apparent, but it’s also a country that was actually a part of the Soviet Union, so their experience of the Soviet occupation was very different than our Polish semi-sovereignty, i.e., being a satellite country of the USSR. The cultural background of Estonia is very different, too, with strong Germanic and Nordic elements. The Estonian language is also very different from Slavic languages. I made sure to visit Estonia earlier, before I even decided on the shape of the show, and I met with a number of artists. Instead of including existing artworks, I decided to commission new projects from two Estonian artists, which was super exciting and I am extremely happy with the results. These were two artists from the younger generation, so to speak – Flo Kasearu and Karlel Koplimets. They both made works about traveling in Estonia today in relation to their own particular histories. By integrating these new works into the narrative of the exhibition, I made an attempt to make “The Travellers” more rooted in the Estonian experience.

Magdalena Moskalewicz, ed., “The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe”. Tallinn: Lugemik, 2017. Photo: Anu Vahtra

On the occasion of the exhibition in Tallinn, you have also put together a special book under the same title, with the Estonian publisher Lugemik. Was this publication created especially with the Estonian version of “The Travelers” in mind?

Yes. I wanted to have a publication for Zachęta, but there was not enough time and resources to make one. This new iteration of “The Travellers” gave me the necessary space to work on the book. It is interesting to publish a book after an exhibition; it becomes a kind of retrospective, self-reflective activity. Once you see the artworks installed in the galleries and working – and by that, I mean relating to each other and to the audience – your thoughts sink in and solidify in a very different way compared to how they took shape in the preparatory stage. I am happy with the collaboration with Lugemik, and also with the encouragement from the KUMU Art Museum to publish the book only in English, so that it circulates better.

The book is not so much an exhibition catalog as more of a publication that accompanies the show. As I mentioned earlier, I think of an exhibition as a thing that’s rooted in a particular place and time, and made for a particular audience. A book travels in a way that you can’t really control. Of course, it is published in a particular language, and you have a sense of its distribution markets, but that’s all. So, this book is intended for a much broader audience than the exhibition – for people who do not necessarily have this experience that we did in Central and Eastern Europe, of the sudden opening of the borders with very sudden excitements and challenges. It includes a part that is like a regular exhibition catalog, with descriptions and images of all of the artworks and an extended curatorial essay that I authored. In addition, I asked artists to share their personal stories of traveling, either related to their art, or simply having something to do with being from Eastern Europe. (Many of them do not live in the region anymore, and some of them are second generation, with only family connections there.) This section comes at the beginning of the book, so it is something that introduces the whole issue to a reader who might not be familiar with these histories. It was an editorial experiment on my part; artists don’t necessarily like to write and some of them did not exactly love the idea at first. But in the end, we managed to get seventeen contributions, all of which work really wonderfully as an introduction to the experience of the generations who lived through that shift.

Sislej Xhafa's Sunshade, 2011 (exhibition copy) at “The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe”, Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn. Photo by Magdalena Moskalewicz

Between the time that you started work on “The Travelers” and until the moment of its second opening in Tallinn, many notable and unexpected things had taken place in the world. It was a critical time in European history, but also in America – I’m referring to the huge influx of refugees, terrorist attacks, changes in governments and world leaders, a troubling rise in nationalism, etc. We are not as open as we once were. Have these events changed your initial ideas and perception of the subject?

I started working on the show in the early fall of 2015, just before the elections that brought a new right-wing government to power in Poland. I was finalizing the checklist as the influx of refugees started entering Europe, an event which would last through the summer of 2016 and later be known as the “refugee crisis”. At that point, I decided to make this show more political than I had initially intended. Originally, it was more about cultural experiences and the poetics of travel, although already influenced by Edward Said, Vilém Flusser, and a few other intellectuals who were once refugees themselves. I decided to include a few more artworks that are openly political and that touch directly upon the issues of contemporary migrations, such as the work of Kosovar artist Sisley Xhafa.

I wouldn’t say that my ideas really changed between the Warsaw exhibition and the Tallinn one. If anything, and I’m not saying this with satisfaction, I feel that it was right to base this exhibition on a reflection of nationalism. This topic comes out in a number of works in the exhibition, and this year I also made sure that it would be visible in the book (through my essay about the post-socialist condition and its links to nationalism). In a way, the topic of the exhibition only becomes more and more valid. Showing it this summer in Tallinn, I felt that actually something I was hoping would just be an element of the whole social and cultural spectrum, is really becoming the main issue.

When I was working on the show for Warsaw, I had this strong motivational urge that, as a curator with a group of wonderful artists, I can actually say something and show something to the Polish audience that would make them realize that, just 25 years ago, we were in much the same situation as these migrants, and that today we need to see that we, too, were once “foreigners”. I really had a very strong, empowering feeling about this. But this summer, exactly a year later, as I was finishing the book in Chicago, I felt that there is not very much that we can, in fact, do. It was an extremely negative and disempowering feeling. Of course, the American election had taken place in the meantime, and that cast a very dark shadow over all of these efforts. This is not to say that we should not continue to fight by using culture, and with as much power as we can. An American curator told me yesterday, as we were speaking here in Chicago about “Halka/Haiti” and “The Travellers”, how these projects are relevant for the situation in the United States now. It was meant as a compliment, but rather than, as the curator of these projects, finding it flattering, I actually found it to be a very bitter realization.

The Travellers: Voyage and Migration in New Art from Central and Eastern Europe. Kumu Art Museum, Tallinn, August 25, 2017 – January 28, 2018. Curated by Magdalena Moskalewicz. Artists: Adéla Babanová, Daniel Baker, Olga Chernysheva, Wojciech Gilewicz, C.T. Jasper & Joanna Malinowska, Flo Kasearu, Karlel Koplimets, Irina Korina, Taus Makhacheva, Porter McCray, Alban Muja, Ilona Németh & Jonathan Ravasz, Roman Ondák, Tímea Anita Oravecz, Adrian Paci, Vesna Pavlovic ́, Dushko Petrovich, Janek Simon, Radek Szlaga & Honza Zamojski, Maja Vukoje, and Sislej Xhafa