Experimental interior architecture exhibition in Tallinn

12/01/2016

Photo: Henno Luts

- “Expedition Wunderlich: 11 interior architects” -

Museum of Estonian Architecture, Tallinn

Through February 28, 2016

Looking much like a Mayan temple from without, the gargantuan Linnahall concerthall – erected in the territory of Tallinn Harbor to coincide with the sailing competition for the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games – takes up an impressive amount of the urban landscape. Although it is now closed and serves only as a landing pad for helicopters, triumphal reminiscences of Soviet Modernism can yet be felt in its interior spaces. Such distillates of the Soviet-era aesthetic are still found in many places throughout the Baltic States, and it is well worth speaking and thinking about them – something that is currently being done by students in the Department of Interior Architecture at the Estonian Academy of Arts, under the tutelage of department head Hannes Praks and curator Carl-Dag Lige*.

“Expedition Wunderlich: 11 interior architects” is an attempt at speaking about space, the creator of the space in question, and the user of the space – all as a united whole. And that is why the exhibition has been created as an almost-intimate, sense-tickling meeting with people who have created such spaces: eleven heavy-weights of Estonian interior architecture and design whose achievements in Estonian architecture cannot be unobserved. Many of the environments created by these masters-of-the-interior are still very much in use today, such as Tallinn's KUMU art museum.

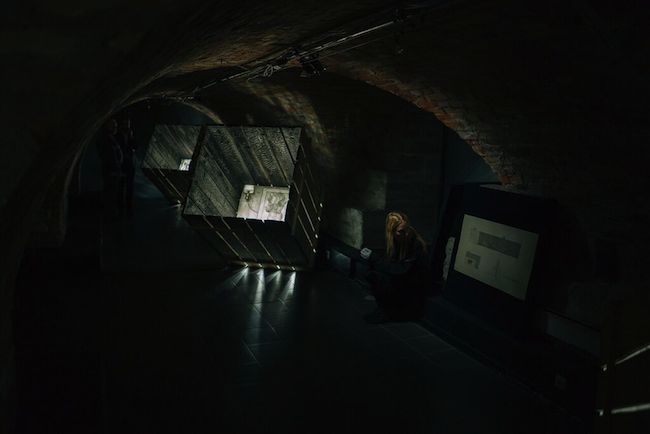

Examples of 1940s-50s Stalinism and 1960s-80s modernism, or architectural utopias and their principles that were never actually erected in real life – in this exhibition, they are displayed in a an absolutely silent and dark basement-level room. “The room, when you enter and when there are no visitors inside, is completely quiet and pretty dark. You spot a few big box-like structures in the vicinity and start walking towards those. There are no hints as to which way you should explore the space, no signs. Once you get close to any of the boxes, a spotlight lights up, and you can see a large black and white photo at the bottom of the tilted box. These are new portrait photos, one of each of the eleven designers and interior architects in their working environment. The images were taken in 2015 by the excellent Estonian portrait photographer Renee Altrov. An audio file starts playing snippets of interviews with the architect. And then, all of a sudden, you notice a person, dressed in a black working uniform, standing next to the box. The person has a stack of original drawings which they will lift up and place under a spotlight for your viewing. These living exhibition stands don’t talk much, but if you ask them specific questions, they might answer, as these are the students who designed and prepared the exhibition. This is is also the reason why the show is only open for one hour (from noon to 1 pm) each Saturday and Sunday – it is practically a theater performance as it requires eleven people to be present to operate the live stands”, explains Triin Männik, one of the people helping the project to take place.

According to professor Hannes Praks, the current head of the Interior Architecture Department, the exhibition deals with the fundamentals of space creation. “When you’re studying to become an interior architect, you deal with opposites – darkness and light, warmth and cold, silence and sound – all things you have to be able to master. That’s why this exhibition, a collaboration between the department and the museum in which current students encompass a pivotal role, was created,” explained Praks. Why was a cellar chosen as the location? “Because the main characteristic of a cellar is, actually, darkness. And darkness is symbolic in many ways regarding the subject matter of the exhibition,” proffers Praks.

Carl-Dag Lige, curator of the exhibition, answered the following questions posed by .

Is it still possible in Estonia to experience public interiors that have remained original and untouched? How much Soviet authenticity does Estonia still retain?

Soviet-era interiors in Estonia have survived only partly. One could say that the situation is better in rural areas and smaller towns where there hasn’t been such strong pressure for financial capital and real-estate development – as compared to urban areas and larger cities, like Tallinn, Tartu and Pärnu. There are some sanatoriums with (at least partly preserved) original Soviet interiors (“Tervis” in Pärnu, “Mereranna” in Narva-Jõesuu etc.). Yet, the most remarkable building with original interiors is definitely the Linnahall in Tallinn (architects Raine Karp, Riina Altmäe, interior architect Ülo Sirp, completed in 1980), which has been closed for several years and the structural condition of which is getting rapidly worse. Another well-preserved interior is that of the Rapla KEK building in Rapla (architect Toomas Rein, interior architect Aulo Padar, completed in 1977). There are others as well, but most of them have been at least partly redesigned.

The creators of this project interviewed eleven Estonian architects and designers who are behind these old interiors. Do they still practice nowadays? Could you mention some examples from their earlier work along with some of their most recent projects?

Still active are Juta Lember, Eerik Olle, Pille Lausmäe and Taso Mähar. Somewhat active are Mait Summatavet, Taevo Gans and Aulo Padar. Bruno Tomberg, Leila Pärtelpoeg, Vello Asi and Teno Velbri don’t actively design anymore, but they still consult other architects and designers if necessary, and are occasionally involved in smaller pedagogical and administrative tasks.

Just to introduce a few of them:

Mait Summatavet is the interior architect of the Ugala theatre in Viljandi (1976), as well as a co-author of the Viru Hotel interiors (1972). His recent works include redesigns for several buildings of the Bank of Estonia. He is also involved in the current renovation of the Ugala theater.

Juta Lember was one of the authors of the Pirita Yachting Centre in Tallinn, built for the Moscow Olympic Games between 1975–80. Her latest works include redesigning the interiors of the President’s Office of the Republic of Estonia, as well as the interior of St Petersburg’s St John’s Church (2011), which is used by the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church.

Aulo Padar, in collaboration with the architect Toomas Rein, designed the main building of the former Linda Kolkhoz in Kobela (1971–73) and the headquarters of the Rapla KEK Construction Company in Rapla (1973–77). Padar was also one of the authors of the Pirita Yachting Centre (1975–80) and the ESSR Political Education Centre (later known as the Sakala Centre, 1982–86; since demolished).

Pille Lausmäe and Taso Mähar represent the generation of Estonian interior architects and designers who studied mainly during the 1980s, but who were more influenced by the severity and minimalism of the then-current Neo-Modernist Finnish architecture instead of the dominant postmodernist tendencies of the time. Both Lausmäe and Mähar have developed a personal, highly refined approach to materials as well as form. Lausmäe’s most prominent works include interiors of the Kumu Art Museum of Estonia (architect Pekka Vapaavuori, 2005), the LHV Bank Headquarters (Alver Trummal Architects, since 2006), and the Viljandi State Gymnasium (Salto Architects, 2013). Taso Mähar, together with the architect Emil Urbel, has primarily designed an abundance of private dwellings, while his remarkable interior solutions for public buildings include the Rocca-al-Mare School (architect Emil Urbel, 2000) and the Rotermann Salt Storage (reconstruction architect Ülo Peil, 1996), both in Tallinn.

What were the main principles behind choosing the people and work presented in the exhibition?

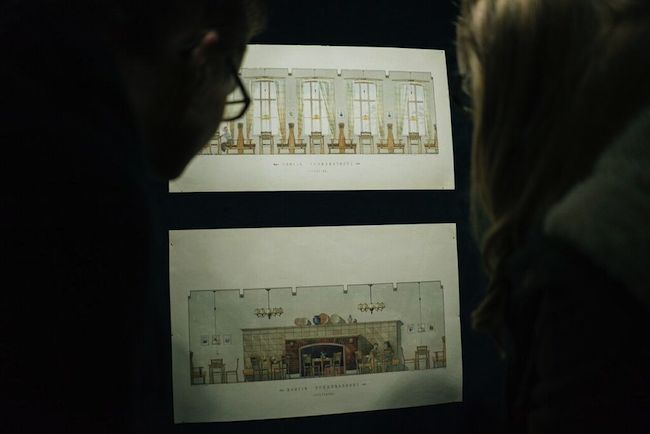

Initially, we didn’t have a rigid conceptual structure that would have helped us select material. Doing extensive work at the Interior Architecture Department’s archive, we realized that one of the main criteria of selection should be the quality of the original drawings. Naturally, we also considered participants in terms of their success as an interior architect or designer; all of those who made the “final cut” have had very interesting careers either as designers, interior architects or educators.

Additionally, we decided to skip all the former heads of the Interior Architecture Department, in order not to emphasize the institutional aspect of the exhibition. The number of persons, eleven, was partly accidental as it was mainly defined by the size of the basement of the museum. We could have included 25 or 40 persons and their student works if there had been more exhibition space and more time for preparation. There are still dozens, if not hundreds, of valuable drawings in the Interior Architecture Department’s archive that could be presented in future exhibitions.

How did you work with the archives?

The archive of the Interior Architecture Department of the Estonian Academy of Art is currently situated in a tiny 10-12 m2 storage space. In February 2015 it looked like a real mess – old printers, vacuum cleaners, lots of dust, old sandals and work clothes, etc. One got the impression that it was more of a dumpster than an archive of student drawings from several decades. Together with Merilin Tee and Katrin Talvik, MA students of Interior Architecture (who were later joined by others students) started to clean the space and browse the archive materials with the aim of getting a preliminary overview. We soon realized that the quality, as well as quantity, of drawings required serious planning and the competence of professional archiving specialists.

In addition to basic cleaning procedures, we aimed to store the drawings properly (many of them were chaotically piled together, crushed between the shelves, etc.). We also started to make a preliminary archive list with short descriptions and photos, as there was no archival system. That work became extremely time-consuming and we soon realized how large the archive actually was. In order to create a selection for the current exhibition, we focused more on earlier decades, especially the period of 1944 -1970.

The archive still needs a lot of work and systematization, but the first step has been taken. Possibly the most important things we found in the archive are Richard Wunderlich’s original furniture drawings from the 1930s – over a hundred small drawings made for the “Uudne Mööbel” (“New Furniture”) furniture workshop where he worked. Wunderlich was the first head of the Interior Architecture Department (1940-41; 1942-44), and it is believed that it was he who initiated the establishment of the field of spatial design at the former Estonian State School of Industry, predecessor of the current Estonian Academy of Arts.

The exhibition is a symbolic homage to the works and professional activity of Richard Wunderlich (1902-1976) – a key figure in the development and professionalization of the field of Estonian interior architecture. He was an interior architect and furniture designer, and the first director (1940-1941) of what is now the EAA Department of Interior Architecture (and from which the eleven designers featured in the exhibition graduated).

-----

* Bio: Carl-Dag Lige (1982) is an architecture critic and historian, a member of the Estonian Society of Art Historians and Curators. He has been a producer, curator and moderator of various architecture events, and currently works as a curator at the Museum of Estonian Architecture in Tallinn.