Surreal Entomology

13/01/2014

Märta Mattsson is a young jewelery designer from Sweden. She has a bright disposition and her persona is quite unlike the type of outer mask one would usually expect of an artist who uses real (albeit dead) creatures in her creations.

Mattsson stresses that she wishes that the wearers of her creations be on a level understanding that under the outer layer of resin, there is a cicada or beetle that was once a living organism. As Mattsson strives to give the creatures a second chance at life through her work, she herself has a respectful and, sometimes, even slightly fearful relationship with them.

Viewers of jewelery are locked into a sort of test mode as they look upon this surreal entomology and are forced to think about what it is that they are seeing – and do they see it as something beautiful, or frightening?

With her works, Märta enlivens a kind of absurd reaction: we are pleasantly enticed by things that we usually would like to avoid. And the idea itself has not changed, only the form – instead of guts flowing out from a dissected bug, bright cubic zirconia tumble out; in addition, there is the illusion that the dead creature is still moving.

Märta Mattsson graduated from the Jewellery Art and Design Program at the HDK School of Design and Crafts in Gothenburg, as well as from the Royal College of Art in London. During her studies, Mattsson also participated in exchange programs in Rhode Island, Hawaii and Tokyo. In 2012 she was awarded the Talent Prize in Munich, and she is currently regarded as one of the most promising young jewelry designers on the scene.

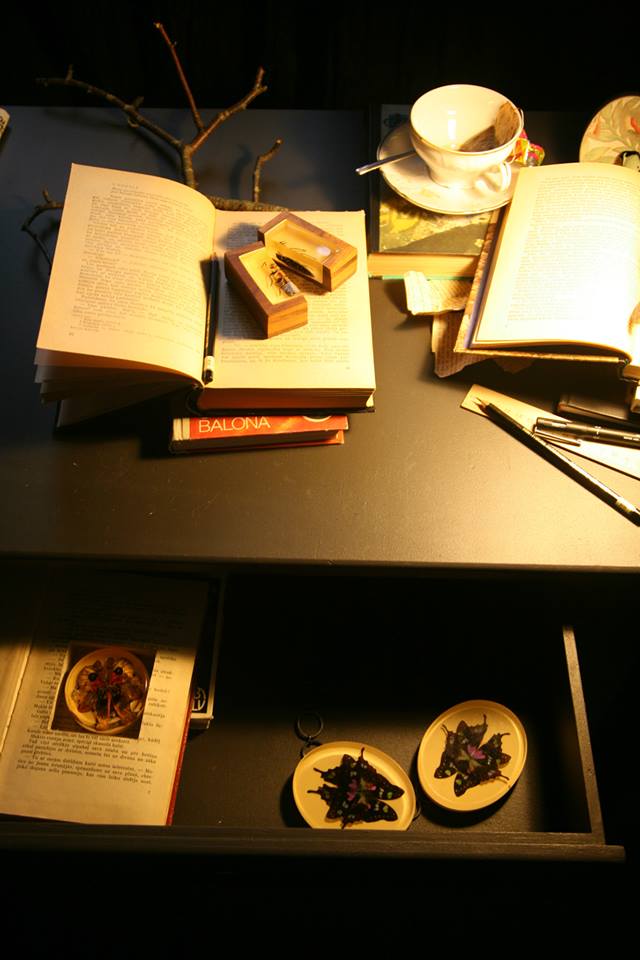

Märta and I met in Riga, in the art gallery “Putti”, which is where her only solo show of 2013, ”Unified in Death”, was being held. I wanted to gain a better understanding of what it was that I was looking at, and how it was made, so once more, we walked the perimeter of the exhibition – as arranged by Latvian audio-visual media artist Sintija Jēkabsone.

Exposition view of artist's solo show, named “United in Death”, in Riga

Märta Mattsson: Since I studied jewelry design for eight years, I believe that I have a rather good understanding of techniques and materials. At first I worked with gold and silver, and with traditional techniques; as my horizons widened, I began to use my own interpretations as well.

I use the electroforming method in my work, the basis of which is similar to the process of gold plating in an electrolytic bath. How does it work? A real insect is covered in a silver coating that conducts electricity, and then it is placed in an electrolytic bath with copper. Through a chemical process, the anions move around and the body of the insect becomes covered in a layer of copper.

I've experimented a lot, and I know when to halt the chemical process so as to achieve the optimum thickness of the copper layer. In working with such a delicate object as an insect, it is important not to loose any of the fine detailing – such as legs and antennae – under the layer of metal, while at the same time, the metal coating must be durable enough for the jewelry to withstand wearing. Each piece takes about three weeks to create.

The process also requires the unpleasant task of removing the creature's innards. That's how I came up with the idea of having shiny cubic zirconia oozing out of the dissected insect – it encourages people to look at something that they usually wouldn't want to look upon. In a sense, it's a play on perception.

In terms of color choices, I try to use ones that are as natural as possible. Even though the insects are dead, I want them to look alive and natural. I also want to grant them movement – the illusion that even though they have been cut open, they can still move around. It's a play on common sense.

For the cicada jewelry, I use a technique that I've developed myself. I wanted to create a kind of modern fossil, so I covered the rather sizable bodies of the cicadas with a layer of pyrite, copper and plastic. So that people could feel the natural texture of the cicada's wings, I've left the top surface of them untouched, and only processed the bottom of the wings in order to give them strength.

Since I receive the insects already dried and pressed, one of the secrets behind this jewelry is that I must always “break their bones” in order to arrange them in life-like positions that allude to movement. This is especially evident in the spider brooches.

Butterflies are usually associated with beauty, which is why in this case, I wanted to challenge myself and reveal a different side to this creature. I've arranged their different wing forms in strange compositions and then set them in plastic resin. Now they look like completely different and unknown creatures, and people have to think about what it is that they are looking at.

The series of brooches made with real headless bird bodies can be either worn, or used as wall décor. People usually place the heads of animals on the wall as trophies, but they throw the bodies out. I thought to myself – why can't I do the opposite? And how will people react? This series is called “Crash”, and it tells about movement. The bird has crashed into a wall, or into your shoulder – as a brooch. In creating these works, I only dabbed with a brush and came up with the idea itself – the rest was done by a taxidermist with whom I work.

Do you often think of death?

Yes, I actually do. I had some serious health problems as a child, so I was forced to think about it quite early on.

My parents were very open about this subject and we freely talked about it. I also spent my childhood at our summer house by the woods, and I had a lot of experience with the death of animals. My mother would find dead animal bones in the forest, and she'd take them home, clean them off and arrange them around the house as decorative objects. I see death as a natural part of life.

Does your interest in using animals in jewelry design also come from your childhood?

I have two brothers. We have all been obsessed by animals since childhood. We collected taxidermy, and we played with snails, bugs and earthworms. My older brother had no qualms in touching them, whereas I felt a certain dislike and fear. I was the scaredy-cat of the bunch. I rather liked the things my mother brought home, but I also feared them.

When we would gather mushrooms in the forest, I wouldn't eat them if they had worms. I didn't like meat, and I still don't eat it.

My older brother liked to go fishing as a child, and I would go with him; I'd pull out a fish, but I would never touch it.

In spite of all this, I was still fascinated by nature and I wanted to become a biologist. When I graduated from high school at eighteen, with a specialization in the natural sciences, I felt that I'd rather work with jewelry design instead.

I had always been interested in it. As a child, I liked to play with my mother's jewelry, and I made my first jewelry collection from wire at age twelve. It was, of course, thematically based on the animal kingdom.

The day after I graduated from school, I signed up for Spanish language courses, but during class one day, I found myself sketching jewelry. Hmm... maybe I should be doing that instead?! After a while, I began to look for jewelry design courses.

I am quick to make decisions, I'm not afraid to try new things, I can easily switch from one thing to another, and I believe that if you want to do something, then you simply have to try and work towards it. This sort of switching sounds irrational, but that's the way I've always done things!

Do you remember how you felt after selling your first piece of jewelry?

I started out by making simple costume jewelry from wire and plastic, and it sold quite well. They were things that I could make quickly and give away without giving it much thought. However, when my jewelry design reached a more serious level – the point where each piece required a lot of investment – it was difficult to let them go. I had to get myself in the state of mind that, if I wanted to work in this field, I had to be ready to sell my work.

Is it important to you who wears your jewelry?

It's interesting to know who these people are; it's nice to meet them. But I'm open to anyone wearing my pieces.

Is there a special person for whom you'd like to design?

Tim Burton. It would be wonderful to design for his films. I've been smitten with his characters since childhood, and they have always inspired me.

In your opinion, what is the most suitable place for your works – someone's personal jewelry box, or an exhibition?

I hope that the people who buy my jewelry don't store them in a box, only to be opened just once a year. That's to be done with other kinds of jewelry; these pieces aren't like that, and they're also not the kind to be locked inside of a bank safe. It is essential that these objects be seen.

At home, I've created a small wooden setting for each piece. When exhibiting my works, I try to integrate them into a natural environment, so that they look as if they've come from nature, and so that the wearer feels as if he or she is wearing a piece of the forest.

With some pieces, I work the object into a wooden or stone base, so that they can be worn already in tandem with a part of the natural environment. I also try to tell a story through the jewelry design itself, such as portraying the act of one creature hunting another.

Exposition view of “United in Death”

What would your ideal jewelry exhibition look like?

Actually, it would be much like this exhibition, in which Sintija has placed each object in its own case.

I like the idea of a huge room in which each object has its own staged environment, and an atmosphere has been created. The focus of attention on each piece of jewelry is fantastic!

Every year there's a huge jewelry fair in Munich – Schmuck. I like to observe the methods they use to showcase jewelry there. I remember this wonderful exhibit that was held in a completely dark room; everyone who entered was handed a flashlight with which to find the jewelry that had been put on display in the room.

How important to you is people's perception of your work?

It's quite important. Since I work with animals, I have to cope with how people might misunderstand, or not comprehend, my work. And the larger and cuddlier the animal, the stronger the reaction. When I work on a theme, I can't allow myself to be naïve and think that everyone will be happy, and that there won't be any issues.

I definitely don't want people to misunderstand me, to think that I don't care and that my only aim is to shock. That's why it's good if I can be there during exhibitions, to talk to people and explain that underneath it all lies my own fear.

Are there any subjects that you avoid in your work?

I don't want to disturb nature, so I'd never touch anything that is protected or endangered.

Sometimes I'm invited to take part in group projects. There was one exhibition that had the female menstrual cycle as its theme. It was organized by two gallerists – a gay couple from Barcelona. This theme is rather cliched already, and I thought that they had invited me with the hope of getting something extreme from me; instead, I presented everything in a very minimalistic manner. I touched upon the sad part of the subject, which is something that men rarely think about – about the difficulties of infertility. It was difficult for me to work with this subject since I am in my thirties myself, and I see the dark side of this subject. In truth, I didn't want to work on this project, and it was a great challenge for me.

How important is it to you to be original in your work?

Very important. I know what's going on in the world of contemporary jewelry design. There are people who do some truly wonderful things, and then I think to myself – if only I had done that. Maybe sometimes I've been inspired to such a degree that the works of others can be seen in my pieces; but then I don't show these pieces. I don't want to copy and I don't want to be copied. But there's a very fine line there.

How many shows have you had in 2013?

I think about fifteen. I had twenty-five last year, and that was much too much. Sometimes I didn't even have enough pieces to show. Last year I had four solo shows; this one in Riga is my only one this year. That's a good thing because I could devote all of my concentration to it, and it contains really special pieces. I've declined some invitations for shows next year because I need time for research and experimentation.

What is this research and experimentation? How do you find inspiration for your work?

I read a lot. I read articles about other artists, the works of critics, art books, and about animals in art. I travel and go to museums – in fact, they seem to be the kind of museums that no one else visits. Last spring I was in Shanghai and I went to a strange museum – it was old and dirty, and the taxidermy done on the animals was in the “fashion” of the 18th century – absolutely disproportional and wrong. I guess that back then, when they got a giraffe skin from somewhere and they had no idea what a live giraffe looked like, they stuffed it however they could.

Do you look for inspiration in art history? The Victorian and Art Nouveau ages made much use of animal and insect motifs...

Art Nouveau was more about aesthetics and the quality of form – about symmetry. My work has more connection to the Victorian era, when people collected various curiousities from nature.

I'm greatly inspired by the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th.

Although contemporary jewelry is a relatively new phenomenon – having started in the 1960s – what would you say are its cornerstones?

In my opinion, it all started with the Dutch designer Gijs Bakker and Droog Design. He could be called “the father of contemporary jewelry”. Those interested in contemporary jewelry should definitely read the book Gijs Bakker and Jewellery.

The Swiss designer Otto Künzli also invested greatly into what we now call contemporary jewelry design.

There weren't many in the 70s and 80s who thought about what a piece of jewelry could be. So, [the designers just mentioned] experimented and widened the horizon. They were pioneers.

Märta Mattsson