The changing attitudes towards Soviet material culture

Keiu Krikmann

22/10/2013

The following essay is mainly a collection of ideas about attitudes towards Soviet material culture that I have accumulated over a period of time.

And just to be clear – I will use the term ‘material culture’, rather than ‘design’, because I want to include everyday objects (both factory-made and self-made) that may not always be perceived as (professional) design; and I will use the term fairly loosely. However, more than the objects, I will be looking into the issue of how those attitudes have shifted. This piece of writing has been inspired by an amalgam of sources that include the presentations at the symposium of this year’s Tallinn Architecture Biennale, exhibitions like Fashion and Cold War at the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn last year, but also my own research, different books and articles I’ve come across, and yes, things on the internet as well. In many ways, this essay also relates to Anna Iltnere’s piece, Post-Soviet Anamnesis, published on Arterritory.com in February 2013.

Everyday objects: plastic milk jug

This year the Tallinn Architecture Biennale explored the idea of Recycling Socialism, which was also the theme of the biennale’s two-day symposium. The very first lecture of the symposium was given by the architectural historian Andres Kurg, who began his presentation by conceptualising the studies of Soviet culture in general. Referring to Alexei Yurchak, he proposed the concept of ‘taking the Soviet era seriously’ – this means giving up the simplistic idea of the supposedly pervasive dichotomy between official and unofficial culture, and addressing the complexities and hybridity of the Soviet period culture, instead. In his book, Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More, Yurchak opposes the notion of ‘binary socialism’, formed upon assumptions about Soviet socialism that most commonly are expressed in the idea that not only was Soviet socialism ‘bad’ and ‘immoral’, but it was also experienced as such by people living in the USSR. This attitude, says Yurchak, led to the use of terminology that heavily applies binary categories like oppression/resistance, state/the people and official culture/counter culture when describing Soviet reality. Notably, these terminologies have occupied a dominant position in the accounts of Soviet socialism in the former West and, since the fall of the Soviet Union, in the former East as well.

Everyday objects: boiling wand

Although Kurg discussed those concepts as a preface to his own presentationabout architecture, they are definitely relevant in the realm of ‘smaller scale objects’ of material culture as well. Yet, when it comes to personal attitudes towards the Soviet period, I think this difference in scale has some relevance. Another presenter at the TAB symposium, architect and critic Petra Čeferin, pointed out that sometimes, in order to move on, it may be necessary to demolish structures (buildings, monuments) that represent an ideology; in a way, those structures become objects of revenge. This relates strongly to the idea of architecture as a tool in the hands of power. The smaller scale objects of material culture, even when produced under the same conditions, are less likely to be seen as representations of a political power.

Still, it seems that for a long time, objects produced and made during the Soviet period were not really valued, but considered ‘lesser’ than those that the new era of capitalism brought into the former Soviet bloc. Due to the wide-spread attitude that goods manufactured in the Soviet Union were of extremely low quality (and they oftentimes undoubtedly were), people easily discarded them when the opportunity to acquire a better quality, or more ‘modern’ versions, presented itself. And although those objects might have not necessarily represented the Soviet state, they did represent a way of life – the Soviet way of life that many wished to swap for a new, ‘Western’-oriented lifestyle. Obviously, the attitudes towards objects from the Soviet era is not exclusively dismissive – people form emotional connections to things they used or someone close to them has used or made. For example, I am thinking of garments that were self-made from paper patterns, and as such, may be valued for personal reasons, but at the same time, they are also a part of the Soviet fashion system. Similar attitudes also seem to apply to objects that were a part of people’s everyday life, like advertisements and all kinds of signs, for example, but that were not part of their personal sphere. Unsurprisingly, by now, when over 20 years have passed since the Soviet Union ceased to exist, nostalgia has become a strong component in the way the Soviet period is viewed, both from personal and academic viewpoints.

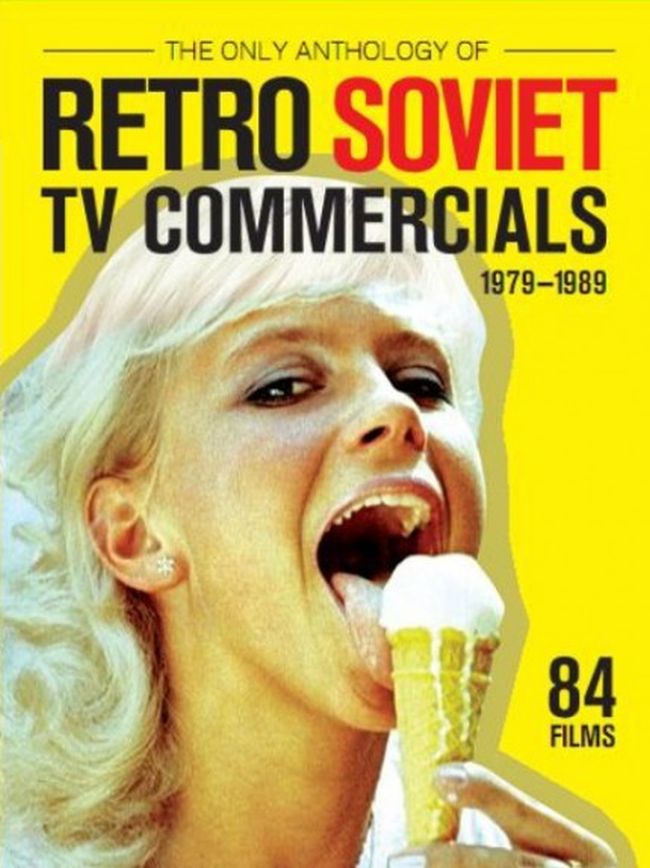

Soviet retro: DVD cover for The Only Anthology of Retro Soviet TV Commercials by Harri Egipt. 1979-1989

Svetlana Boym distinguishes between two main types of nostalgia, and I find this distinction relevant in this context. In her essay, Nostalgia and Its Discontents, Boym writes: “Restorative nostalgia stresses nostos (home) and attempts a trans-historical reconstruction of the lost home. Reflective nostalgia thrives on algia (the longing itself) and delays the homecoming—wistfully, ironically, desperately. (…) Restorative nostalgia does not think of itself as nostalgia, but rather as truth and tradition. Reflective nostalgia dwells on the ambivalences of human longing and belonging and does not shy away from the contradictions of modernity. Restorative nostalgia protects the absolute truth, while reflective nostalgia calls it into doubt.”

From the project My Most beloved Dress: a dress worn by two generations

Although Boym briefly discusses how nostalgia for the Soviet period in Russia often falls under the category of restorative nostalgia and is ‘sponsored from above’, in Estonia, nostalgia for the period seems more to be of the reflective kind. That is, of course, not to say that restorative nostalgia has not found its place in the mechanism of construction of Estonian history; however, its object is somewhere else – it is reserved for the time of the republic before the Soviet period. Nevertheless, it seems that, as enough time (however much that may be) has passed, people now enjoy reminiscing about the Soviet era. This is evident in the surge of 'the Soviet retro’ in the commercial sphere and also in popular culture: from comedy series about life during the Soviet period, to soft drinks that taste “just like they used to” and retro-styled bands. Soviet material culture and design are going through the process of rehabilitation on an institutional level as well – two of the most recent examples of this trend are the exhibition Soviet Design in 1950s-80s, in the Moscow Design Museum, which even reached the international press, and which was soon followed by Packaging Design. Made in Russia. Not having seen those exhibitions personally, I would rather refrain from making assumptions. Instead, I will use the example of another recent exhibition – Fashion and the Cold War, at the Kumu Art Museum in Tallinn.

From the project My Most beloved Dress: nylon jackets worn by two generations

In many respects, the curators of Fashion and the Cold War (Eha Komissarov and Berit Teeäär) utilised nostalgia for the Soviet era – or to be more precise, nostalgia for garments from that period – in their marketing strategy, but they also incorporated the (nostalgic) experiences of ‘ordinary’ people into the exposition. And I say this without a hint of disdain; on the contrary, I think that the project, My Most Beloved Dress, was a splendid addition to the exhibition. The project was started six months before the exhibition opened, and the aim was to collect visual material and recollections of dresses (and other pieces of clothing) that, at some point in their lives, had been significant to ‘ordinary women’. Later, the visual material, along with the accompanying stories, was displayed at the exhibition. It is worth pointing out that, throughout the exhibition, the curators strongly opposed the simplistic approach to Soviet fashion – which usually disregards the agency of people who, professionally or not, were a part of it, and which treats it like a peculiarity without taking it seriously. So, instead of immersing in Soviet nostalgia just for the fun of it, it was used as a strategy to normalise the outlook on the period.

Kvas tank exhibited in Tallinn, 2011

This raises the broader question of how to present and discuss Soviet material culture in a way that would not portray it as bizarre, bleak, worthless, or merely with nostalgic overtones. There is a lot to consider – as Svetlana Boym notes: “It is always important to ask the question: Who is speaking in the name of nostalgia? Who is its ventriloquist? Twenty-first-century nostalgia, like its seventeenth-century counterpart, produces epidemics of feigned nostalgia. For example, the problem with nostalgia in Eastern Europe is that it seems more ubiquitous than it actually is. This might appear counter-intuitive. Western Europeans often project nostalgia onto Eastern Europe as a way of legitimizing “backwardness” and not confronting the differences in their cultural history”. Although she specifically addresses the issue of nostalgia, the question of ideology behind the representations of material culture is relevant in a considerably broader sense. But I don’t think it is so much a question of ‘the West’ imposing its view anymore – the Cold War/East–West opposition is not worth clinging to; it is more about how these representations contribute to the construction of histories within local and global contexts.