Tallinn Tests Out the Idea of Self-Driven Cars

Q&A with Marten Kaevats, Curator of the Third International Tallinn Architecture Biennale (TAB)

24/09/2015

From September 9 to October 18, the Third International Tallinn Architecture Biennale (TAB) is taking place at two locations – at Kultuurikatel and at the Museum of Estonian Architecture. In exploring this year’s theme – Self-Driven City – the Biennale analyzes the consequences of the third industrial revolution, or, how the latest technologies will change architecture, urban planning and everyday social processes. Tallinn’s ambition is to become the first city in Europe to start using only self-driving, or driverless, cars. The pilot project for this idea will be launched in 2018, when Estonia takes over the presidency of the Council of the European Union, and the complete transfer to driverless cars is set to take place 15 years from now, in 2030 (whereas Dubai has set the same goal for 2020).

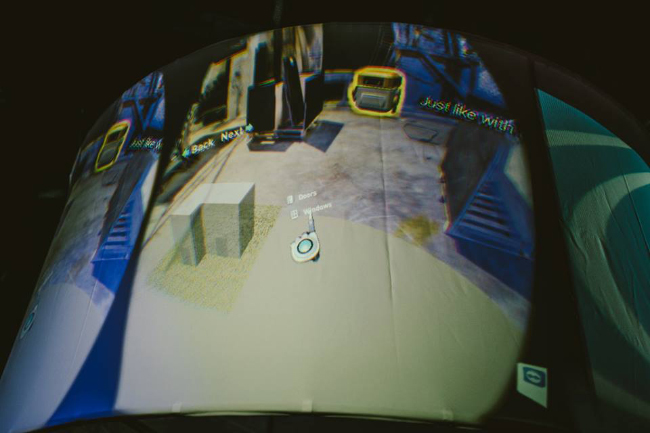

On view as part of the Biennale is the exhibition Epicentre of Tallinn, a showcase of the competition that searched for and modeled answers to the question of how driverless cars will change the city's landscapes and the public space as a whole. Tallinn's busiest and most problematic intersection, on Viru Street, was used as the platform for the competition – with the hope that the intersection could someday again become a public square.

But what does such an ambitious goal mean for architects, designers and urban planners? What does it mean for the city itself and its citizens? What are the necessary steps for preparing for such a transition? On the morning of the Biennale's opening, Arterritory.com met with Marten Kaevats, an architect, urban planner and the curator of the Biennale. Kaevats says, “In a way, Estonia is the ideal model, or test platform, for such a project. As opposed to, say, Germany or Great Britain, we are a relatively small country, and therefore we’re able to implement changes more quickly and we can more efficiently solve any problems that might come up. In addition, if Merkel makes a mistake with Germany, because of the country's size and large population, it becomes a big problem in the long term”.

TAB Vision Competition Epicentre of Tallinn exhibition by Arhitekt Must. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

What has to be changed in a city's infrastructure so that it can handle self-driving cars?

Actually, we could say that driverless cars are a kind of symbol. They’re a technological tool that embodies the essence of the digital age. For an average-sized European city, a complete transfer to driverless cars means a ten-fold reduction in the number of cars on the roads. And urban planning can then continue without so much thought to parking spaces, traffic jams and so on. For example, complicated intersections and multilevel interchanges will no longer be as necessary, and so the city itself, its streets, and the way people live in it will radically change. Cities will become greener and more user-friendly to its inhabitants. But, in order to implement all of this, the most essential thing is to first change the way we think. And what we can begin with right now is a sort of ‘acupuncture’ for the city. Select a small neighborhood, or maybe just one street, and turn it into a pleasant urban space. Until now, the planning of public spaces was more the domain of traffic engineers, but from now on it should be landscape architects who do this type of work.

In addition, the current infrastructure is completely suitable for driverless cars, so in this sense, no additional investment is needed. Yes, of course, we’ll need the cars themselves, as well as servers and control systems, but there should be no need for making fundamental changes in the existing infrastructure. The changes are more likely to be psychological. It’s not possible to introduce a new technology by just telling people it’s going to be great. No, they need to understand the possibilities, the negative aspects and so on. In essence, the changes each of us will individually face in our own neighborhoods will also let us experience how our quality of life improves. My daughter just started first grade, and of course, I tell her that as soon she leaves the house, she has to look right and look left, making sure that there aren't any oncoming cars. The space outside of our home is, in a sense, a source of fear for her right now. Once you go out, you have to engage a heightened sense of alertness. This will all go away. Implementation of the self-driven concept will make the public space a place without fear. You'll be able to send your kids downtown, or out with friends to play football, and you won't have to worry about them getting into a traffic accident.

What, in this case, will happen to traditional cars? Will they be prohibited?

No. I think that in the future, there will be a mixture of everything. Nevertheless, the self-driven concept undoubtedly means big changes everywhere – in production, in society. About five percent of people will loose their jobs – those who currently work as drivers, or who work in the services related to this field. At the same time, people will have much more free time to devote to their their so-called hobbies. For instance, some may start collecting old cars, or some might want to show off to their girlfriends with pimped-up cars... This will all still go on, but at the same time, the environment will have completely changed. There will no longer be traffic signs, but people will become used to that and they will respect the situation.

But what's going to happen to those five percent who will loose their jobs?

That is essentially an issue of education and employment retraining. The state educational system should not prepare so many people for these professions. Since the implementation of self-driven systems doesn't require huge investments (actually, we're more likely to save money by not having to fund new intersections and overpasses, which tend to cost hundreds of millions), a part of this saved money can be used for tactical solutions and job retraining, thereby making the transitional period more balanced. Of course, there will me media scandals when, for instance, a self-driven car hits a child. These sort of things will happen, but it will be only a small fraction compared to the number of traffic accidents that take place in today's system of transportation.

Casagrande Laboratory exposition. Photo: Ardo Kaljuvee

But when this sort of model is implemented, what happens to the joy and freedom of sitting behind the wheel yourself? It is no secret that for a part of society, the automobile has always been not only a functional form of transportation, but a status symbol and a validation of one's ego. And in the end, expensive cars are also the auto industry's largest money-makers.

Access to information has greatly changed society. The 'open source' principle is at work today. That means that even big corporations no longer have the ability to hide away ideas that are unwelcome or disadvantageous to them. Information accessibility means that if someone has a good idea, then that's a good idea that can be applied to the whole world, and if some “corporate bad guy” wants to keep it locked up, someone elsewhere in the world will pull it out again. That's why the word 'self-driven' has two meanings. One definition is applicable to cars, and the other designates processes that people or organizations undertake even though there is no outright reward. These initiatives are supported by specific groups of people or by an overall enthusiasm.

For their part, automakers have already found a solution to this situation. In the coming decades, automobile companies will transform into mobility companies that instead of selling cars, will be selling kilometers. Basically, in ten years you will no longer be buying a new car from BMW, but rather – kilometers. And since the cars themselves will belong to BMW, the selling of kilometers is how the automakers will make money from then on. That's the only business model in which income can be maintained along with a drastic reduction in the number of cars. Of course, there will still be wealthy people who will want to own their own cars, but there will be much less of them compared to now.

In a sense, it's an issue of choosing your weapon. For me, it's always been a positive narrative – to use instruments in a positive manner; to set the direction in which we want to go. Of course, it's never going to go exactly as hoped for. Because there are always a lot of different and hard choices to be made in the space between coming up with the idea, and reality; but I still believe that a positive dream is a good instrument with which to achieve something.

The symbol of the first industrial revolution was the steam engine. And it was precisely the steam engine that instigated all of the changes that took place. People began to move to the cities, production concentrated there, and the number of inhabitants began to climb drastically. It is still increasing, and according to predictions, it will stabilize at around 10 billion. That's the only thing that we can accept as a given right now. With an increase in the number of people, the level of innovation will also increase. Actually, today we have to come up with a new steam engine on a daily basis. The rate of change is accelerating. Much like in the case of refugees, or in any other matter – we cannot know what it will truly mean, and in addition, the playing field is constantly changing. The only thing that we can do, and what the Bienniale is also covering – is talk about the ability for separate groups to change, and learning to understand the changes and this new way of thinking as a whole. And that's something that has to be done everywhere, throughout the world.

Body Building, the main exhibition at TAB, explores how architecture is moving beyond the common borders of the discipline – how architecture and science have entered into a dialogue by way of the new territories of building aesthetics and spatial qualities as created by self-driven intelligent systems. The exhibition consists of prototypes and installations executed by ten international architectural studios.

We offer an insight into the Tallinn Architecture Biennale exhibition.

Body Building. Sille Pihlak's and Siim Tuksam's installation in front of Museum of Estonian Architecture. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

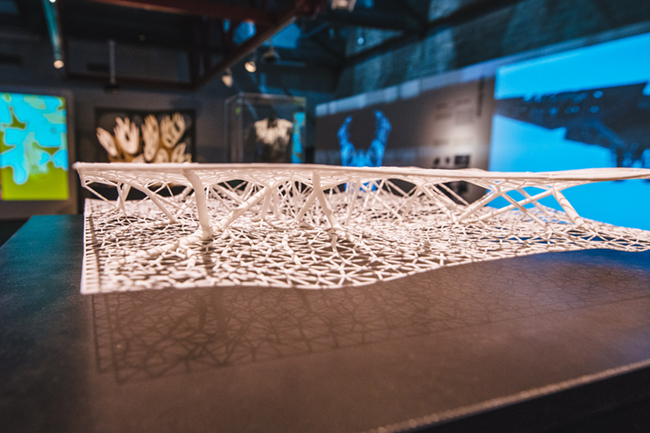

City Form Lab | Andres Sevtsuk + Raul Kalvo. Grid Structure (2015). Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Informations. An Atlas of Experiments in Materialized Information (2015). Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Tom Wiscombe Architecture. The Figural Joint (2015). Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Kokkugia | Roland Snooks + Robert Stuart-Smith. Behavioral Prototypes (2015). Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Latvian exposition World Without Architect?. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Latvian exposition World Without Architect?. Photo: Tõnu Tunnel

Latvian exposition World Without Architect?. Photo: Vladislava Snurnikova