Commentaries on the Venice Architecture Biennale, and on the Estonian and Latvian Pavilions

14/07/2014

Almost one month is has passed since the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale has opened, and it will be open to visitors throughout the summer and autumn, up until November 23. The head curator of the Biennale is Rem Koolhaas, who this year assigned thematic frameworks for the national pavilions; as a result, the pavilions are dominated by an overview of the legacy of modernist architecture. Estonia and Latvia are participating from the Baltic States. We asked several architects and architecture critics their thoughts on the central exhibitions curated by Koolhaas, as well as for commentary on the Latvian and Estonian exhibitions.

Ann Mirjam Vaikla, Scenographer (Tallinn/Oslo)

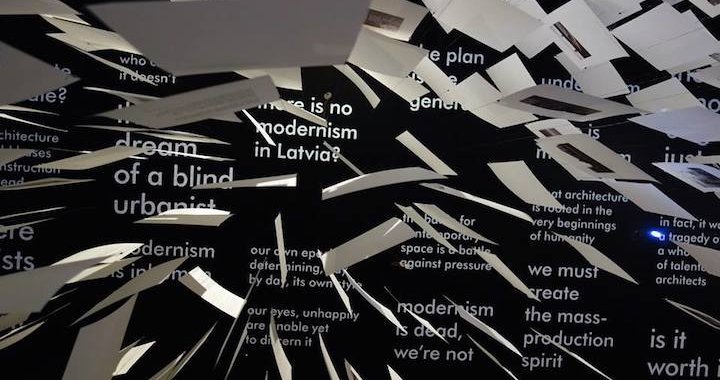

The Latvian pavilion, Unwritten, caught my eye with its installation-value. The hundreds of paper sheets hanging closely next to each other in the air, forming a dialogue with light and sound, creates a holistic, sensory space. Letting myself go along with these spatial characteristics, I noticed, one by one, the honest content of the sheets: provocative, humorous (e.g., “modernism is sexy”) and informative, and shifting with stunning photos of Latvian modernist architecture – it captured me in a bubble like some “never-ending story”. Unwritten is an ambitious and continuous study of the modernism era – a theme that is little-known and rarely used and, in many cases, abandoned. One could criticize: Where will all of these unanswered questions take us?

I find it relevant to create a common ground by raising questions that also refer to the 13th Architecture Biennale, at which the Estonian exposition asked, in the theme of abandoned modernist architecture: “How Long Is the Life of a Building?” Mapping the last century with questions is a starting point for investigating our shared cultural heritage of modernist architecture.

In following these thoughts, it could lead to a future idea for a shared pavilion, one that would create a cohesive identity for the Baltic exposition.

The Estonian pavilion, Interspace, is, theoretically, intriguing, with its focus on public space that is created by both the physical and digital public spheres. In practice, it became too much about focusing on national identity through forming the notion around “e-stonia”. The temptation of having an interactive floor at the exposition interfered with my understanding of an overall concept, and made me question on what scale is it an illustration of public place-making.

“Bungalow Germania”, the exposition of the Belgian national pavilion. Photo courtesy of the pavilion

My favorite is the German pavilion, Bungalow Germania, which embodies the pure essence of modernism. Playing with strong spatial and political contrasts, the reconstruction of the Kanzlerbungalow, built in Bonn in 1964 by modernist architect Sep Ruf, is almost reigned-in by the characteristics of the pavilion itself, designed by Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, in 1938. The dialogue and dynamics between the two spaces allow for the space for a third – an in-between space that is filled with the sound of singing birds.

Vladimir Belogolovsky, Architect, Curator and Writer (New York)

I suppose the Koolhaas Biennale is my favorite so far. I have been to every Architecture Biennale in Venice since 2006 and, in my opinion, this one is the most cohesive and stimulating, as well as controversial and desperate in terms of reexamining conventions and circulating ideas.

The controversy is clear. We architects must be exploring form-making, yet we are ashamed of talking about it. We are discussing ecology and social inclusion at the expense of searching for meaningful and inventive forms in response to programmatic, cultural, regional, and many other particularities. We abandoned form-making as our most supreme duty (what inspired most of us to become architects in the first place), and now we are inquiring: ‘Why has our architecture become interchangeable and indistinguishable just about everywhere?’ We attack the world’s most distinctive architects by branding them artistic, signature, iconic, “starchitects”, etc., and we praise generic fluff. Now that we have succeeded in loosening the distinctions, we are again looking for origins and particularities.

Still, I applaud the idea of rediscovering the fundamental elements of architecture. At the very least, we cannot afford not to know our own (global/local) history. New technologies allow us to bring into focus elements of architecture which, for a long time, were considered ‘not modern’, and were almost entirely removed from professional discourse. In fact, the most celebrated buildings of late hardly feature elements at all. Now, at the Biennale, our art is turned into a desperate trade show of elements and ideas – anything goes, anything we like, anything we can afford.

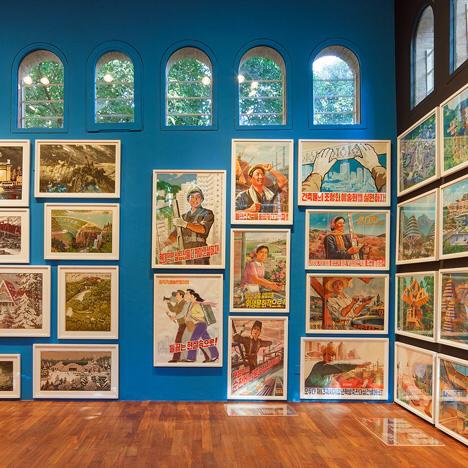

The exposition of the Korean national pavilion. Photo courtesy of the pavilion

The Korean Pavilion (focused on two divided Koreas) was given the Golden Lion, which reinforces the notion that architecture is political more than it is artistic. The top award spells this out explicitly. Many pavilions brought to Venice their countries’ best achievements of the last century. America celebrates its global expansion through architecture and its generic model of corporate culture. Russia tries to ‘sell’ its great Soviet avant-garde projects from the 1920s and ‘30s, which already inspired the world, but curiously, to this day, seem to remain irrelevant to Russia's own, many subsequent generations of architects. The French Pavilion focused on four particular local failures of modernism. This critical approach traces how architecture, no matter how well intended, can turn into a nightmare. Still, there is more to learn from such projects than from those celebrated as ‘successful’ ones.

“Interiors. Notes and Figures”, the exposition of the Belgian national pavilion. Photo courtesy of the pavilion

Aesthetics was taken to a very high level this year and while, for example, Belgium turned its display into a one-dimensional fetish, derivative of its own presentation four years ago, purely visually, I loved the British Pavilion, which demonstrated that architectural shows not only can tell stories and ask questions, but can also be delightful in looking at.

The Latvian Pavilion is searching for meanings in the architecture that was built in this Baltic State during the time of the Soviet occupation. Its installation confronts visitors with provoking identity questions about architecture that is of little distinction and low quality. Iconic stature was not achieved there, and it is what’s causing such acute anxieties. All this makes me believe that we should avoid, at all cost, giving up on achieving iconic and distinctive architecture in our own time. Architecture must target at providing emotional experience through formal and spatial means; all other aspects, no matter how significant, are supplementary.

Triin Ojari, Director of the Museum of Estonian Architecture (Tallinn)

Despite the criticism addressed towards the star system, the ambiguity and predictability of the Biennale exhibitions, and despite the fact that the biennale (or triennale), as a format, has been reproduced actively all over the globe, the Venice Biennale arouses interest, speculations and great expectations. One of the challenges for the Biennale is the ability and readiness to renew itself, to come up with new ideas and formats. This year’s Biennale did that more effectively than many previous ones. Probably the organizers could have congratulated themselves already at the moment when Rem Koolhaas agreed to curate the Biennale – he's one of the most famous provocateurs and theorists in contemporary architecture, and his success relies on good knowledge about the elements which define the current built world, as well as on his extremely good communicational strategy. Rem’s main exhibition, Fundamentals, was definitely a critical project: the well-presented and ambiguous history of the basic elements of architecture as walls, ceilings, bathrooms, balconies, etc., reflected, in fact, his position towards the freedom that exists in the architect’s profession in the current era, its limits, and its historical basis. Koolhaas has already been accused of being too pessimistic, of saying “We Are All Doomed”, of offering no positive program. I met many architects in the opening who missed the visions of “a brave new world”, architectural projects of tomorrow, the overview of things which are usually presented in Venice. Since my background is in architectural history, I enjoyed the “history of simple things” very much. Sure, it was also a criticism towards the traditional way of writing architectural histories, and of the way our thinking about originality and freedom in architecture is actually defined by the way history is taught at schools and presented in books, exhibitions etc.

“Interspace”, the exposition of the Estonian national pavilion. Photo courtesy of the pavilion

The Estonian exhibition, Interspace, curated by the very young architects Johan Tali, Siim Tuksam and Johanna Jõekalda, was one of the exceptions in the general picture of national pavilions. Their interest lied in the intersection of physical space and virtual space, how virtual reality eventually affects and influences the power-lines and behavior present in real urban spaces. Estonia, as a state, manifests its e-democracy and its readiness to fluently embrace all new technological innovations, and the Estonian exhibition was clearly affected by this optimistic view. Since there are no clear answers yet to the realm of interspace, and to where it will eventually lead us, it was quite difficult for the young curators to present it in the exhibition room, to actually “build” it and, eventually, to create an understandable and emotional space out of it. There were more questions and vague, pixelated images than clear-cut historical lines visible in many other national exhibitions as well; but surely, the questions can be far more interesting and thought-provoking than comprehensive answers.

“Unwritten”, the exposition of the Latvian national pavilion. Photo courtesy of the pavilion

The Latvian pavilion impressed me with a good and simple design idea – a “cloud” of images of Latvian modernism and the hope to establish a basis for a wider national research database of Latvian Modernist architecture. The questioning of the status of the Modernist heritage is a very relevant one – the uncritical nostalgia towards the period’s aesthetics and design, as well as neglect of the social ideas embedded in the Soviet period’s buildings – is common for many post-socialist societies, I guess. People live in many different realities nowadays: in the same moment and virtual world described in the Estonian pavilion, and in the acknowledgement of the heritage of Modernism presented in the Latvian “cloud” – both express the unending study of Modernism put forward by Rem Koolhaas' concept.

Zaiga Gaile, Architect (Riga)

I haven't felt this elated and satisfied after a visit to the Venice Architecture Biennale in a long time! I am finally seeing a moving away from bubbles, spires and other monsters of narcissistic pretentiousness and competition – that made it seem as if we were heading for the end – but none of it pertained to me. Already four years ago, Rem Koolhass, the curator of this Biennale, began talking about the dead-end towards which modern-day architecture is heading. I remember his OMA exhibition at the 2010 Biennale. Back then, Koolhaas wrote: “Having always been interested in the past, OMA has been heavily involved with projects concerned with the issues of time and history since the office’s inception 35 years ago. The present illustrates the perfect friction point between two directions: the world’s ambition to rescue larger and larger territories of the planet, and the global rage to eliminate the evidence of the post-war period of architecture as a social project. Both tendencies–preservation and destruction–are seen to slowly destroy any sense of a linear evolution of time.” OMA received the Golden Lion for their Biennale showing in 2010.

Staircase ideal standards in different periods . Photo: Zaiga Gaile

The definition of this Biennale – fundamentals, absorbing modernity – continues with the thought and invites a return to basics. It is more like studying rather than creating anew, and a step back is necessary to come to one's senses and think a bit. It is not possible to cross out a period in history, to lock it outside of consciousness. What should be done with post-war modernist architecture? How should we act towards it?

The Biennale's international exhibition in the Arsenale is screening clips of post-war films – Antonioni, Fellini, Godard, Pasolini – the presence of architecture in people's lives and relationships. On one screen, huge buildings, whole neighborhoods, bridges, towers, stations, etc. are continually being blown up. The “Elements of Architecture” exhibition in the Central Pavilion studies and demonstrates the fundamental parts of a building – walls, floors, ceilings, a roof, a window, a door, a corridor, a bathroom, a balcony, stairs, an elevator, a ramp, a fireplace – and the evolution of their development. This rich and multifaceted exhibition was created by several universities and colleges; a lot of work was invested in it, and they've put on display historic windows, doors, detailing, parts of walls, floors and so on. You don't have to be a student to want to spend months in just this pavilion. And then there's the third large pavilion, Italy's exposition, which moves you with its diversity and good architecture. Most of it is renovations of historical buildings and their absorption into today's environment and way of life.

Latvia's exhibition truly moved me, and I'm saying that from the heart. We cannot build large-scale exhibitions with real building projects, as do, for instance, Spain, Switzerland, Holland and Italy. And we don't have to. The cognition of Latvia's post-war modernist architecture is more like that of a young person discovering it and then asking: What is it? – A valuable piece of our heritage, or something that should be destroyed? Should it be restored, or remodeled into something else? Is it already broken, defective? What should we do, for instance, with the abandoned Presses nams (Press Building), and who was responsible for taking down “Jūras pērle” (a seaside resort/café) and “Sēnīte” (a popular roadside café)? Why did we allow the degrading remodeling of the elegant modernist architecture of Riga's Central Railroad Station and the Hotel “Latvia”, right in the heart of Riga? What can we expect from the overhaul of Riga's Central Bus Station? Uldis Lukševics and his NRJA team (NO RULES JUST ARCHITECTURE), who have always stood out with provocative architecture that adheres to their manifesto, began their application for creating the exhibition with the phrase: “THERE IS NO MODERNISM IN LATVIA”. Over several months, as they looked through the participants' on-line submissions of examples of modernist architecture, their statement developed into a question: HOW TO WRITE A RESEARCH PROJECT ON POST-WAR MODERNISM IN LATVIA? UN-WRITTEN! It hasn't been written! The flashing neon sign on a large screen has transformed into a fragile and sensitive cloud made from thousands of white pieces of paper hung by a piece of thread, some of them with black and white images of structures, while many others are completely blank. The white cloud of paper vibrates with every gust of air that comes from the open door or that we breath out. To be courageous enough to question as sensitively as a child. It is to come back into health. As I was leaving, I also took a copy of the just-as-fragile publication, UN-WRITTEN, in which Uldis inscribed: “Modernism is sexy!” That is also about emotions.

What can I say about the Estonians? The digital games with a flat space are too complex for me, and I get lost. It is without emotions. Two presidents speak in the niche of a space, and between them is a model of Tallinn in which they have illuminated everything that has been built around the historic city center in the last two hundred years. A good piece of work.

The day after I returned from Venice, a Sunday, I walked through the mountain that is the new Latvian National Library, alone. Quietly, dimly and peacefully. The books have already arrived and now live on the light wood shelves. It's good and beautiful; I calmed down! On the previous Friday, the builders opened the building to the public, and we got the news in Venice right before the opening of the Latvian exhibition. Two happy events were linked together.

Matīss Groskaufmanis, Architect (Riga/Rotterdam)

As a whole, this year's Venice Architecture Biennale left me with a kaleidoscopic impression. It came to a climax in the days right before its opening – at the moment when there were almost too many impressions around. The place was full of plastic glasses of prosecco, architects dressed in black and sweating under the Italian sun, and a brutal – at times, panicky – exchange of contact information while groups of people huddled around smartphones, trying to decipher the hastily re-photographed addresses of that evening's party spots. This is all on the backdrop of the wildly varying national pavilions which, in spite of the specific request of the Biennale's curators, have all been executed very differently. While some try to capture the visitors' unstable attention with films, impressive structural models or slogans, others experiment with exhibition/display methods, or transform their exhibitions into discussion clubs and improvised architectural offices. At the same time, other pavilions unassumingly display facts about the past and today, occasionally drowning in obedient banality, sometimes surprising one with their quietness among the overall noise.

“Unwritten”, the exposition of the Latvian national pavilion. Photo courtesy of the pavilion

In this sense, Latvia's contribution to the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale is one of the best that could be expected, considering what we were given to work with – a traditionally late call for submissions and weak interest from the intended audience. It's more of a stroke of luck than a progression of logical events that the team that applied was able to, in a short time, get it together enough to at least start a localized discussion around this year's theme. Although the terms “modernism” and “modernity”, as mentioned in the Biennale's curator's call for submissions, can lead to various interpretations, the creators of Latvia's exposition focused on modernism as an era of architecture, and the remnants of its legacy that can still be found in Latvia. The exposition doesn't fully answer why the Latvian condition should be interesting to others besides themselves; however, it does lay the groundwork for placing the seemingly isolated “Latvian condition” into a context that is broader and potentially more interesting for the rest of the world.

In contrast to the last exposition in 2012 – in which the inescapable, post-soviet issues facing Latvia's inhabitants were looked at as a subjective, very individualistic story about inner freedom and the romantic facades of Riga's streets – this year's exhibit features direct language; poorly translated into English, bet understandable. In addition, the most valuable remnant is not the spatial installation with the fluttering pages of an unwritten book, but the unwritten book itself. It contains not only a photo index of modernism-era buildings found on social networks, but also essays on the presence of 20th-century architecture in Latvia and its place in the architectural doctrine of the Soviet Union. Even though the readable part does not surprise with a ton of new revelations, it is definitely more than just a few drops in the modest bucket of Latvian architectural theory.

“Interspace”, the exposition of the Estonian national pavilion. Photo courtesy of the pavilion

In terms of the Baltics, Lithuania didn't participate at all, while most of the Estonian exhibit consists of an interactive, but not informative, projection; therefore, the objective of discussing the digitalization of public space left the impression of being more of a technical, not critical, project. Much like the Estonian “pavilion”, Latvia's “pavilion” took up little room in a large space, and that's why it would sometimes practically disappear among the crowds of visitors. Perhaps that is why the subject of creating a unified Baltic pavilion at some future Biennale – like the Nordic countries already do – popped up occasionally in unofficial discussions going on at the Biennale. Although that would definitely be one way to emphasize their presence and increase their visibility, first of all, it is a conversation about how much the Baltics truly have in common – if we don't count our common borders, shared problems, and the architecture of Lithuanian supermarkets.

My personal favorite is “Monditalia”, the exhibition at the Arsenale overseen by OMA and Ippolito Pestellini, specifically; its indefiniteness and pluralism contrasts with the main exhibition in the Gardens – “The Elements of Architecture”. “Monditalia” talks about modern Italy's glory, and misery, by showing both its treasures and trash, mixing them into clever or simply aesthetic research projects, poorly selected performances, and installations that encourage brain activity. In this way, “Monditalia” proves that a “national” pavilion is not always the best way to get a look at a specific country and its situation. Perhaps this is where interesting motifs for future Biennales could be found.

Kristīne Budže, Architecture and Design Critic (Riga)

At the “Greenhouse Talk” discussions organized by the Dutch embassy and held in the days preceding the opening of the Venice Biennale, the architecture historian Michelle Provoost presented a conspiracy theory: that as a skillful manipulator, Rem has beautifully achieved the seemingly opposite effect of the original request presented to the national pavilions. Everybody focused on their own country's individual and special features, thereby contradicting the notion of modernity's unifying character. Nevertheless, no matter how Rem orchestrated it, everyone agrees that the quality of this year's national expositions is higher than in previous years.

On a different day at these same “Greenhouse Talk” discussions, sharp words were exchanged concerning Chandigarh, India, a city designed by Le Corbusier; Cino Zucchi, an Italian architect and lecturer at Milan's Politechnico and Harvard, mentioned the city as a good example of modernist urban planning. This was cuttingly refuted by the Indian architect Bijoy Jain, who said that Le Corbusier's city structure is foreign to Indians, and that since the city's founding in the 1950s, its inhabitants have been struggling against the city by attempts at assimilating it and making it suitable for the Indian way of life. Jain also reminded everyone that Eastern architects will always be in a state of conflict with their Western colleagues, and that their task will always be to work within this conflict. I should mention that this is not the only example of Eastern architects having a skeptical view of their Western colleagues' zeal of bringing their principles to other parts of the world. Westerners usually ignore these sort of opinions, which is why my favorite at this year's Biennale, in terms of theme, is the Nordic pavilion's (Finland, Norway and Sweden) unified exhibition, “Forms of Freedom. African Independence and Nordic Models”. It is about the African countries that gained their independence in the 1960s, and the consequential Scandinavian architects' attempts to transfer their life- and architectural-models to Africa; the failure of this attempt of a Northern import is freely admitted.

I usually look at Estonia's exposition at the Venice Architecture Biennale with professional envy, but this year it disappointed me. Perhaps my expectations were too great, but it seemed to me that the Estonians had tangled themselves up in their own thematic objectives of public space and digital technologies. The exhibition was dominated by didactic Estonian self-congratulations on Estonia being the most technological developed e-country, and lacked an analysis and evaluation of the complex and ambiguous nature of technological public spaces.

Inese Baranovska, Director of The Museum of Decorative Arts and Design, Riga

I was so intrigued by the persuasive “Monditalia” exhibition that I went to see it at the Arsenale three separate times – and every time I discovered something new. After such a vibrant display, the rest of the national pavilions in the Arsenale rather paled in comparison; or, using sports terminology, they were in a different weight class. Both Estonia's and Latvia's expositions are proper and indicate Northern restraint. However, I believe that both exhibits have the same, one fault: the interactive participation of the viewer has not been properly thought out – what is being displayed is so dense that it can simply be passed by. Nevertheless, Latvia's exhibit – with its asceticism and laconic simplicity – contrasts well with what the other countries have on offer. The most valuable part of the exhibit is the fact that, for the first time, a collection of writings and a research study on the development of modernism in Latvia have been completed and assembled. Exhibitions come and go, but the research results are permanent.

“Clockwork Jerusalem”, at the United Kingdom's national pavilion. Publicity photo

In mentioning my favorites of the national exhibitions in the Arsenale, I must highlight Chile (it was nice to hear that they ended up getting the Silver Lion); the Albanian exhibition, “Potential Monuments of an Unrealized Future”, was emotionally powerful; and just as excellent is the large-scale, conceptually thought-out and elegantly designed “Innesti/Grafting” – Italy's national exhibition based on the “modernism laboratory” that is Milan. In the Gardens, my personal favorite is the UK's exhibition, “A Clockwork Jerusalem”, with the ability to, as always, take an ironic look at its history as a world superpower. Also notable are Spain (3D interiors), France and Korea (Golden Lion). Daniel Libeskind's special project, “Sonnets in Babylon” was also effective, but that's another story altogether...

Helvijs Savickis, Architect (Riga/Vienna)

“Modernism is dead!” said Zarathustra as he climbed back onto dry land. The funeral was opened on June 4, in Venice. Truly – a very beautiful funeral. But let's remember that one doesn't just cry at funerals, but one is also happy, sings for joy, celebrates and honors the deceased's best moments. I saw something similar at this year's Venice Biennale. The two main questions hovering about were: What can we learn from modernism?, and, How can we live with modernism?

In an interview with Dezeen, Peter Eisenman has stated a truly interesting opinion on Rem Koolhaas. (Eisenman was the first person to give Koolhaas an award, and in the 70s he helped publish the decisive book, Delirious New York. Koolhaas began his glorious ascent with this book.) In the Dezeen interview, Eisenman criticizes the exhibition, “Elements of Architecture”: “First of all, any language is grammar. The thing that changes from Italian to English is not the words being different, but grammar. So, if architecture is to be considered a language, 'elements' don't matter. I mean, whatever the words are, they're all the same. So, for me, what's missing [from the show], purposely missing, is the grammatic.”

Photo: Helvijs Savickis

What he's speaking about here is the Koolhaas-curated exhibition in the Gardens, in which 15 rooms contain 15 university studies on the most diverse architectural elements – floors, ceilings, stairs and a dozen others. The exhibition has become a museum, a very educational museum that cultivates thinking and that makes architecture take a look back at the fundamentals.

I remember a vivid moment when I was standing by a vibrating machine that was polishing door handles. Every five minutes, it would vomit out a couple of handles, which would then fall into a box with 500 other handles just like them. Behind every handle is a room – most likely in some high-rise building. So, every handle must be drawn in by a drafter. But that's alright, because it only has to be drawn once, and then you make 500 copies of it... A friend from the Taiwanese pavilion runs up to me and slaps a sticker into my hand: “Here, stick it up somewhere!”, and he runs off distributing more stickers. I didn't stick it up anywhere, but I brought it home as a souvenir from Koolhaas' exhibition. I get a flash of an idea that Rem has always referred to the powerful influence of the 1968 event, i.e., Guy Debord's book, The Society of the Spectacles.

Chile's pavilion. Photo: Helvijs Savickis and publicity materials

In terms of choice of a theme, my favorite is Chile's pavilion in the Arsenal – in the same room where Latvia's exposition was located in last year's 55th Venice Art Biennale. As the visitors enter the first room, they find themselves in a hyper-realistic living room that has been set up in a very homey manner, and in which an old married couple from a block apartment complex in either Purvciems, Moscow or Italy have lived out a peaceful and harmonious life. Passing through this living room, we enter a large room in the center of which stands a prefabricated, reinforced concrete panel – the main key point – and around which lie all of the problems connected to it in Chile. For instance, the lime must be imported from Africa. More than 20 different panels have been put on display, and we are informed of how difficult it was for the architects to manipulate these blocks in order to reach their goals of creating a better and more homey environment for people, as well as how it was this specific material that influenced modernism throughout the world. The pavilion's exhibit has been excellently put together, and it was awarded the Silver Lion.

Although this was the first year that this pavilion participated, and it really doesn't fall under Venice's requested unifying theme, I really urge everyone to visit the Nadim Samman-curated Antarctica-Antarctopia pavilion, which is located in the heart of Venice, between the Realto and Academia Bridges.

Zaha Hadid's and Alexander Brodsky's projects in Antarctica-Antarctopia pavilion. Photo: Helvijs Savickis

The exhibition is like an attempt at rehabilitating the utopian potential of the South Pole. Included are 15 architects from around the world who have created projects in the Antarctic. A truly beautiful interaction arises from the placing of Zaha Hadid's project next to that of Alexander Brodsky, who has dreamed up a small, poetic chess pavilion – because it is so quiet... Whereas Zaha Hadid's offices have created a ferry docking station with lodgings for some 7000 people.

The creators of the Estonian pavilion have, for the first time, made steps towards cooperation between the Baltics, namely, including in their project the Latvian Reinis Adovičs, who created the interactive technical side of the exhibit. I really hope that after a few years there will be a Baltic pavilion, since our ideas and problems are relatively similar, and by combining our strength, we could start hoping for recognition with awards from the Architecture Biennale. But overall, I'm waiting for the release of the Estonian pavilion's webpage, which will be an interactive environment linked to the installation. Only then will the concept be fully realized.

The exhibit at the Latvian pavilion is successful in its formal execution; in its lightness, the exposition completely embodies the ethereal idea behind the concept. In my opinion, its content is excellent and completely corresponds to Koolhaas' request and the Biennale's mood, and at the same time, it presents a large theoretical investment in the formation of a comprehensive history of Latvia's architecture. Along with the exhibition, the NRJA has published a fantastic, unfinished book, “UN-WRITTEN” – a lasting object of value containing essays by Juris Dambis, Jānis Taurenis, Arta Zvirgzdiņa and Vladimirs Belogovskis, as well as Nikita Khrushchev's December 7, 1954 speech that was looked upon as the starting point of modernisms in the soviet world. The question: “When did modernism die?”, is left unanswered in the book, even though none of the elite architects of the time, such as J. Lejnieks and J. Paegle, don't deny the demise of modernism – with the exception of Kronbergs, who asserts that modernism will never die, and that a transformation of metaphysical ideas is occurring.

Even though the question: “When did modernism die?” is important only from a theoretical viewpoint, and even though everyone tries to find some notable event concerning modernistic structures in their own corner of the world – such as the 1995 dismantling of the soviet radar station in Skrunda, or the finishing of the National Library in 2014 – I propose my own version: modernism in Latvia died at 4:15 P.M, June 5, 2014, which is when the exhibition in the Latvian pavilion was opened. The grandiose and beautiful funeral will last until November 23. I recommend experiencing such a historic event.