Romance with Space. Contemporary art and architecture

Gleb Yershov

22/08/2013

The plotline of the relationship of contemporary artists with architecture is, first of all based on possibilities of presentation that are new to art. It is the vacant industrial buildings, the huge, alienated from the economy spaces in factories and industrial complexes that have lost their functional purpose and become redundant. These territories with their once impressive industrial potential are quickly “losing weight”; they are no longer any evidence of power – just the opposite, they testify to powerlessness and inability to change anything; the energy that once reigned there is no longer capable to support this superhuman, megalomaniac and titanic scale of grandiose social utopia. As a result, these abandoned workshops, assembly lines and gasworks are quickly fading, they are taken over by pillagers; no longer looked after, they fall to ruin and are inhabited by all sorts of accidental people – from the homeless to temporary tenants who keep there their goods. All this reminds one of paintings by Hubert Robert or Alessandro Magnasco (particularly his «Banditti at Rest» amongst ancient ruins).

Painting by Hubert Robert

The industrial is now in the past, replaced by a different economic and cultural order. If in times past, culture centred around the factory as a temple of Labour, a truly holy place where the proletariat was forging its golden communist future, today, with the collapse of Soviet ideology, these temples are destined to become our antiquity while our times could hardly pass for the era of New Testament...

Contemporary art has the opportunity to inhabit these abandoned territories and is using it as best as it can. New exhibition spaces are installed where a whole variety of events, happenings, festivals take place; new types of real estate, the lofts, have appeared and the previous industrial centres have become fashionable centres of culture where the “creative” class can enjoy not only galleries but also boutiques and restaurants.

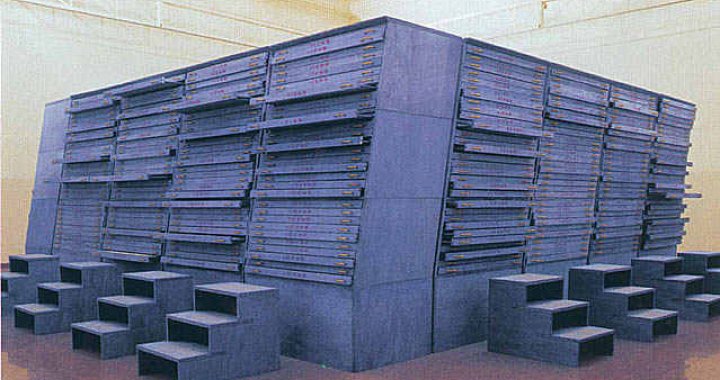

Installation by Anselm Kiefer for “Monumenta”

With the greed of crusaders having entered Constantinople, artists have been busy enjoying the rich spoils. And that is hardly surprising: they have got the chance to populate these abandoned spaces with their things. Just think of the scale! It is like the boldest fantasies of Piranesi have come to life. The grandiose scale, however, cannot be conquered by just anyone. Evidence for the growing ambitions of contemporary art is «Monumenta», held at the Grand Palais complex built at the end of the 19th century for the express purpose of housing industrial expos there and echoing the famous “Crystal Palace” in London. The exhibition with the works of “heavyweights” of contemporary art represented in it reflects in its own way the changes that have taken place. In 2007, “Monumenta” was opened by Anselm Kiefer, followed by Richard Serra (2008), Christian Boltansky (2010), Anish Kapoor (2011) and Daniel Buren (2012). Thus the artist is given the hitherto unknown opportunity to work with large spaces that can be compared to the Cyclopean scale of the era of industrialization. Installations become not simply total, to use the term applied to the works of Kabakov – they become a part of inhabitable architecture, themselves becoming that architecture.

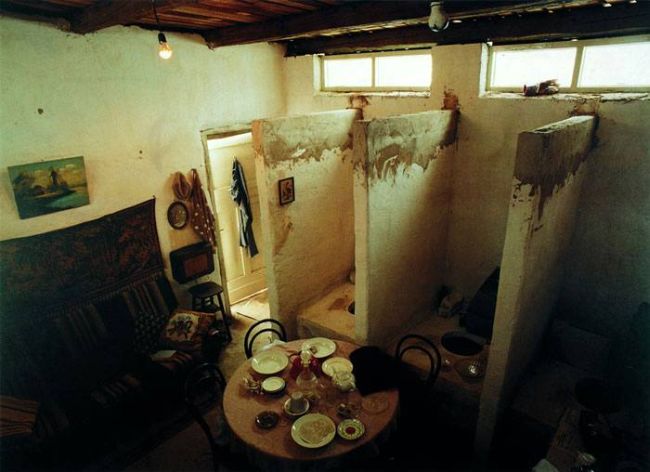

Incidentally, one of the first total installations of Kabakov, his famous “Toilet” at the “Documenta” in Kassel, was one of the first attempts to appropriate typical Soviet architecture of what is known as the “small scale”. It is “Toilet” with its poor, pitiful “non-form” (but not without a touch of Soviet minimalist modernism that led to constructivism) became the epic endeavour that opened the era of appropriating the bleak Soviet architecture to contemporary Russian artists. Having imbued it with the pedestrian cosiness of Soviet everyday life, Kabakov managed to humanize this soulless concrete architecture.

Installation of Ilya Kabakov “Toilet” at the “Documenta” in Kassel

The second ingredient in the romance of contemporary artists is Time: the takeover of the space of the Past inevitably assumed the presence there of huge reserves of time, dreaming and dozing in that space. Hence – melancholy and sentimentality, the characteristic romanticization of ruins. One tends to go numb – an effect characteristic of a holy place where the experience of time sharpens and seems to be reversed. Conservation of Time takes place with the help of visual organization of space. An artist does not rearrange anything, he works as a stage director of space, which has become an ideal matrix for his ideas. Since the categories of collective social consciousness no longer function in the holds of these abandoned ships and their futuristic and utopian origins have evaporated, the mechanisms of personal, individual memory – and fate – come into play. Remythologization of the past, which never has become the future, is taking place.

Alexander Brodsky. “Cisterna”

It is no accident that one of the most noteworthy artists working with architecture as space of personal memory and individual experience, Alexander Brodsky, loves so much to work with the most dreary, standard forms of Soviet architecture. His work «Cisterna» is extremely subtle, finely wrought piece on organizing ones experiences of space as something extraordinary: many have noted an almost cathartic and temple-sacral feeling as they encounter... well, what is it exactly? After all, Brodsky did not change the space, it remained the same: a dull, dark space of a natural gas-filling station. On the walls, he put windows – light boxes with white, slightly stirring curtains. Having changed nothing in the construction, he changed the image of the space that evokes associations with the magic of the sacral universe of a Byzantine temple. This indicates the need of the contemporary man to experience space as a sacral sphere, for contemporary architecture practically does not work with these “outdated” categories of perception; rather it is characterized by technocratic clarity.

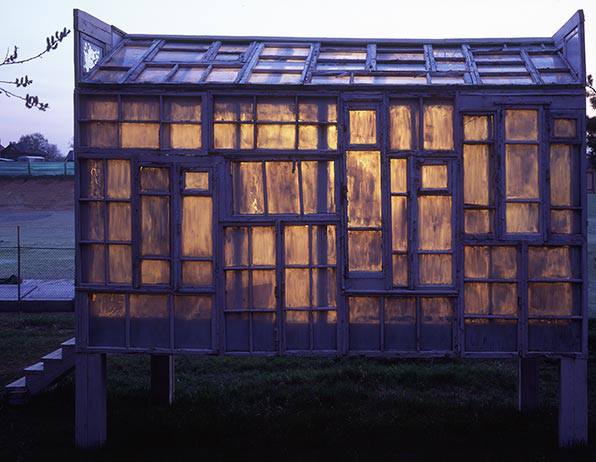

Another work – «Pavilion for Water Ceremonies» – at first glance, a makeshift dacha steam-house, put together from old, broken window frames, also, albeit in an elevated ironic way, comments on the essentially functional form as if it were almost sacral, given the undisputable cult of the consumption of liquids in Russia. This small-scale form, referring to the ceremonial 18th century with its tea pavilions, bird-houses and gazebos brings to our attention the wide distribution of that kind of nameless structures that are rooted in the quotidian and are an integral part of the Russian landscape. His pavilion looks almost ready-made, because its unforced quality: it seems not to have been conceived in imagination but rather found somewhere around the dacha. To Brodsky’s credit, it is almost a nameless structure, which organically corresponds to the “canonical” form and very technique of building genuine “masterpieces” of spontaneous folk architecture.

Alexander Brodsky. “Pavilion for Water Ceremonies”

The theme of «dacha architecture» – is also one of the most important for contemporary artists. Just ten years ago, Pavel Pepperstein mused that artists should pay attention to dacha architecture as genuine folk architecture, which, although unrecognized, is capable of creating new non-canonical forms. During the last decade, many artists have turned precisely to this kind of non-professional architecture, making interesting discoveries along the way.

Valery Koshlyakov, master of scotch-art, painter of monumental scale and power, is one of them. He turned to architecture, having thought of a new name for his objects, “iconos”, to designate the forms related to icon and connected to tent architecture and, according to the artist, appropriate for the structures his father built at their dacha. From the formal point of view, Koshlyakov’s “iconoses”, really show proximity to the logic of building architectural forms onto icons with their extraordinary, non-classical and disfunctional nature. The graphics of Russian constructivists also looks good in them, whereas by their crazy form, spontaneously filling space they remind one of the “Merzbau” gradually filling interiors for Schwitters.

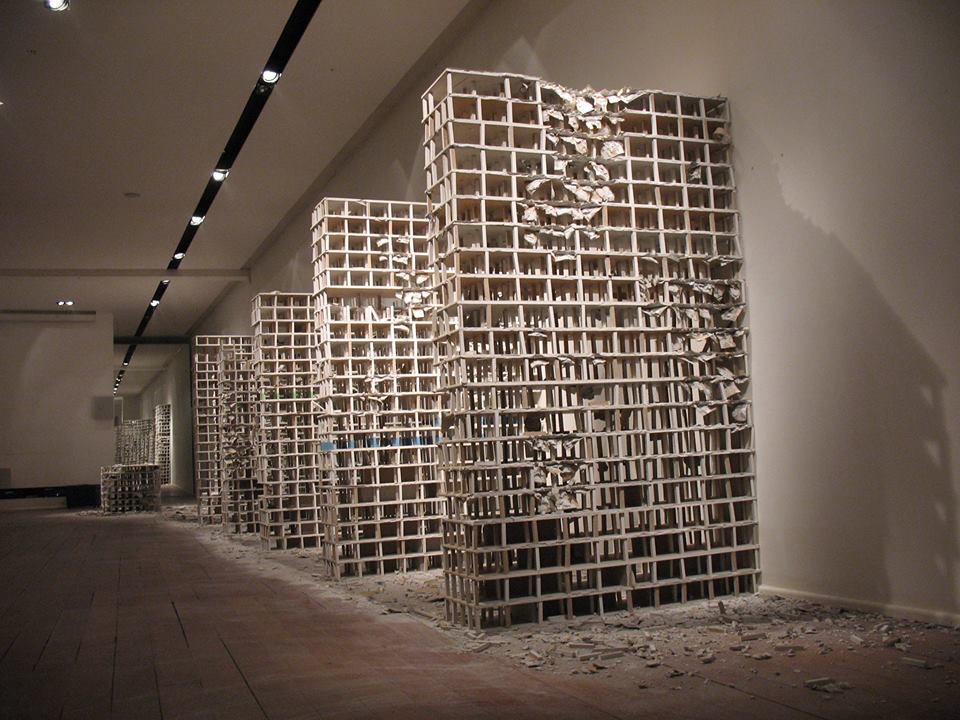

In his projects of the last decade, Pyotr Bely likewise turns to the theme of ruins, making installations in the spirit of «memorial modelling”. Both Koshlyakov and Bely are inspired by the powerful, bleak and grim textures inherited from the Soviet period: they could be called “Piranesi of Soviet runis.” Recently, Bely has shown that he is not indifferent to the poetics of chaotic, self-organizing form; he is getting his inspiration in construction sites, temporary constructions and structures erected for repairs.

Pyotr Belov’s objects

This line of “folk architecture” has found reflection in such exhibits as “Russian Beauty” and “Russian Poor” at which were presented various testimonies to inventiveness, cleverness and imagination both by anonymous self-educated masters and artists who are boldly continuing along this path.

Nikolai Polissky seems to speak for a never discontinued folk fairy-tale imagination based on archetypical thinking akin to primal, ante-historical ur-forms of human structures, such as, for example, a tower, a ladder or a gate. He is right in stating that his art can be viewed as a version of tardy Russian land-art. From the architectural point of view, his creations, made of simple materials, natural for the Russian peasant, such as hay, birch bark, twigs, logs and poles that have experienced a kind of rebirth due to the return of the theme of peasant architecture where Scandinavian design, popular in Russia, has lately played a role. At the same time, it is the line of ecological and organic architecture that tends to cultivate natural materials, forms that are based on various forms of the natural world or “non-solid” geometry. It reminds one of the 1970s with the then characteristic attempts to leave aside the too geometrical architecture and return to the earthiness of the countryside.

Similar is the phenomenon of «paper architecture»; in the late Soviet period, this term was introduced by architect Yuri Avakumov, who was one of the first Russian post-modernists in architecture, resorting to sophisticated intellectual quoting of Soviet classics (the Mausoleum,

Tatlin’s tower, “Workman and the Kolkhoz Woman”). The revolutionary projects of Soviet constructivists of the 1920s, which remained on paper because they actually defined their time, just like the architects of the “mutinous” architecture of the period of the French Revolution, Boullée and Ledoux, can be listed in the genealogy of “paper architecture”. In the 1980s, one of such “paper architects” was also Brodsky who can be considered a representative of conceptual architecture. The paper architecture of the end of the 20th century revealed its very tight connection to the language of contemporary art, with its conditions of representation and totality.

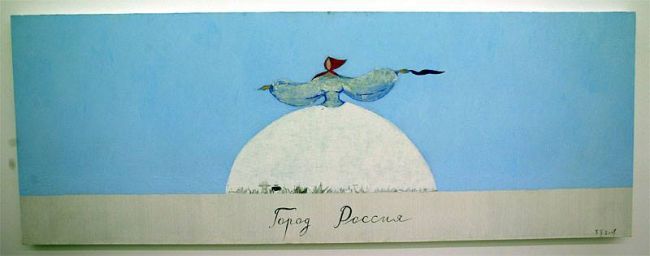

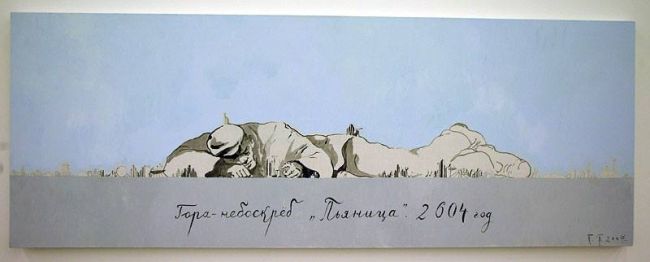

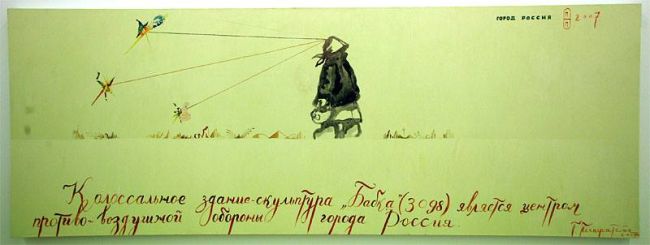

An anti-utopia or rather schizo-utopia, which is based on the most incredible fantasies about the city of the future, is present in the clever project by Pepperstein “Russia City” (2007). It is centred around the civic position of the artist, who sent his project, along with an open letter, to the president of Russia. In the letter, Pepperstein calls for the historical capitals of Russia, Moscow and St Petersburg, to be left alone and for building a new one instead, halfway between the two, and to name it Russia City. From a completely sober and intellectually sound message that presents clear arguments for preserving the historical sites, the author imperceptibly moves on to the fantastical arch-idea of philosopher N. Fedoreov about the Resurrection of the Fathers, which contains the source of both Russian cosmism and avant-garde. The utopian thought of the beginning of the century returns, revealing its “mythogenic” nature. Pepperstein turns to archetypical figures of Russian life: “Skyscraper “Drunkard”, 2064” and Colossal Building-Sculpture “Broad” (3098), which are supposed to be the air-defense centre of Russia City; the Russian beauty who has hidden the city under her teacup skirts and is swirling in a dance; and the Malavinian vortex, the “Group of Skyscrapers “Lead Singer” above Russia City in 5010”.

Works by Pavel Pepperstein from the project “Russia City” (2007)

The counter-reliefs of Tatlin and the Merzbau of Schwitters grew out of the flat surface, beginning their movement toward three-dimensional space with the help of separate fragments of the world of objects, are exempt of any kind of utilitarian purpose. Tatlin’s development toward architectural forms of scale took place owing to the revolutionary era, which gave leftist artists the opportunity to think of the future on the utopian scale of the imminent social brotherhood. The Merzbau of Schwitters became a sign of inhabiting another, in all likelihood individual, space of his own artistic illusion. It is an example of an expansion of an artist’s will outward – his striving toward developing his own “hermitages”.

Kabakov’s installations likewise flow from this primary source of creating one’s own metaphysical space of otherness, which would possess its own inner rules, different from the banality of the quotidian. His models of futuristic constructions in the spirit of the vertiginous projects of Russian Constructivism can, ideally, be realized, yet their purpose is different: the vector of their creator’s thought points not to the future but to the past instead. They are reservoirs of time past, a kind of cenotaphs, mnemonic constructions with the aim of preserving the traces of their metaphysical characteristics, for example, dreams of the future of the Soviet man. For that purpose, the entire communal mythology of the artist has been developed; he strives toward totality, i.e., toward a full exit into a different dimension of space and time.

This is how contemporary art has finally transferred the very possibility of constructing a different space of life from the utopian future to the area of historical reconstructions, romantic revisions of the past with unexpected detours in space and time where it is possible to have a paradoxical juxtaposition of quotations from an endlessly extended sphere of images that we have inherited from the past.