“Art is always a question for me”

An interview with German art collector Egidio Marzona in Berlin

30/03/2015

The German art collector Egidio Marzona is a unique personality. One could say that he is an archiver of 20th-century art. Having started his collection in the 1960s, he has amassed one of the largest collections of conceptualism, minimalism and arte povera in the world. More than 150 artists are represented. But that is not all – Marzona has also documented the entirety of the art process that took place in this period of time: in the formats of drawings, sketches, collages, photographs, postcards, exhibition catalogs, letters and so on.

In 2002, Marzona gifted his impressive collection to the National Museum of the City of Berlin and to the Hamburger Bahnhof. When the Mies van der Rohe-designed Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin opens its doors again after reconstruction work led by the British “starchitect” David Chipperfield, the Egidio Marzona Collection will be put on view. The large-scale, three-year run of the exhibition “A-Z”, as part of the Marzona Collection, is currently on view at the Hamburger Bahnhof.

But that is not all. If you ever find yourself in Italy, in the village of Verzegnis in the Friuli region, you will see the gesamtkunstwerk that Egidio Marzona has created on the Marzona family estate: a sculpture park that also serves as a home for art, open to visitors 24 hours a day. The art here is everywhere – on the grounds and in the buildings. Richard Long, Dan Graham, Robert Barry, Carl Andre, Peter Koegler, Sol LeWitt and Bruce Nauman, among others – they have all created works specially for the Verzegnis Sculpture Park. “I live in a house where every corner, every room has been created by an artist. I usually perceive my living spaces as a container. This one is the only exception.”

Among other things, the Friuli region has wonderful trout fishing spots, and Marzona does not hide the fact that he is a passionate angler. In addition, Venice is only an hour's drive away, so during the Biennale he usually has a lot of friends come over. However, in terms of the Biennale itself – in its current incarnation, that is – he is quite critical. “I think it is silly to take advantage of art for the sake of an international competition. It's been made to be like football. At the Biennale, everything is based on this national mindset. And that is truly childish and silly. Nevertheless, it is a great place to meet friends that come together every two years – from Australia, South America, New York. In my opinion, that is the best thing the Biennale has to offer.”

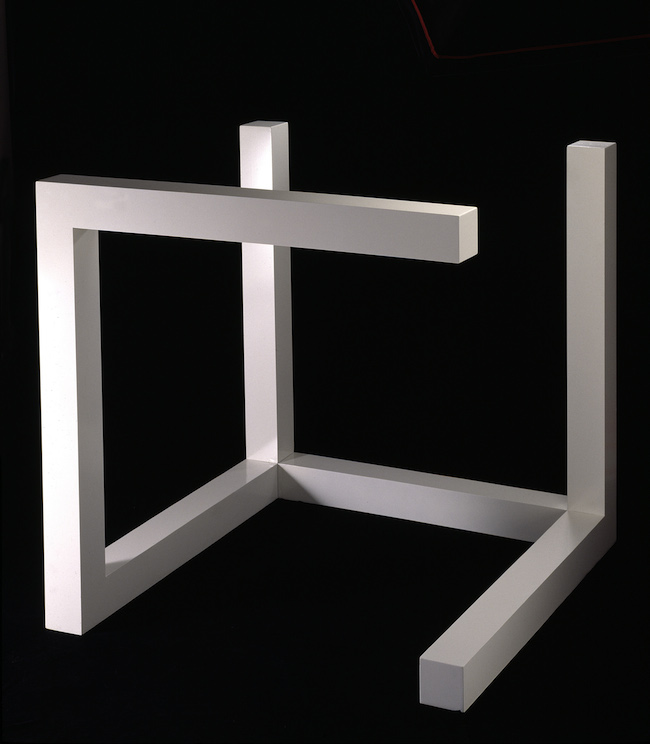

Richard Nonas. Untitled (1993) in the Art Park of Villa di Verzegnis. Photo: Marcus Schneider

When I met with Egidio Marzona in his home in West Berlin, which is also where a part of his massive archive collection is stored, I have a noteworthy opponent during the first twenty minutes or so of our conversation – Anton, Egidio's dog. Anton ceaselessly vies for attention until finally, either tired or admitting defeat, he lies down right there by the couch. Throughout most of our conversation, Marzona puffs on his pipe, despite the fact that he has a cold. He possesses an air of charmingly unobtrusive wisdom and charisma. Later on he takes me down to his basement archive, which is actually a whole library. My first impression is one of shock, for in front of me I see a multitude of shelves holding a multitude of tightly packed folders with orange bindings. These folders contain everything – letters written by artists, postcards, invitations to exhibition openings, newspaper clippings, catalogs. Among them is an envelope with an invitation to Yves Klein's first show in Scandinavia, in 1963. The postage stamp – or rather, its imitation of one – is in Klein's legendary shade of blue, with the requisite perforated edges. A separate shelf is devoted to performances. “I have bought all of the documents linked to them: photographs, invitations, letters – in order to preserve those moments.” When I ask Marzona how large his collection is, he answers that he has no idea. “I think that I have more than 1.5 million units in my archive. That's more than Getty*”. Less than ten percent of the archive is in his home. “I have four large warehouses in Berlin.” On the first floor there's a rather large room that is reminiscent of an artist's studio. One of its walls is covered with small-format drawings and paintings. Among them are works by Duchamp, Matisse, Picasso and Arp. “They're all originals,” Marzona tells me as he removes some from the wall to show me their backsides – which are sometimes a historical story all their own, occasionally giving something away about their previous owners. “I think it is important that students not only work with the archival information, but that they can also physically touch real, genuine artworks. This is not a possibility in museums.” Marzona's current big project is the development of a public research center. It is both his mission and his life's work.

Installation view of Arte Povera room. A-Z. Die Sammlung Marzona, Sammlung Marzona. Photo: Staatliche Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart / Thomas Bruns

How did your fascination with art begin, and how did that develop into collecting?

I lived in Düsseldorf for a while in the 60s, and the gallerist Konrad Fischer was a good friend of mine. I hadn't been thinking of creating a collection. The first work that I bought from Fischer was a painting by Robert Ryman. Then I started buying something from most of his exhibitions. Mostly conceptual art, minimalism and Arte Povera. At the beginning of the 70s, I founded my publishing house in Düsseldorf and I became preoccupied with something completely different. My publishing house specialized in 20th-century modern art and design. We published very many books on Bauhaus, for example. I closed the business down in 1993. At the current moment I am only a collector. An alchemist.

I've heard that you also have a large collection of Bauhaus drawings.

Yes, that was the start of my archive project. Right now it is my main subject of interest – I'm developing a research center. Something similar to Getty's, but focusing only on the 20th-century avant garde. From futurism to postmodernism.

As a collector, were you keenly focused from the very start?

No; in the beginning it was simply contemporary art. Then I turned to publishing. I am not an art historian, and the publishing house was also a learning process for me. I did the research for all of my books myself. During the time that I was closing the publishing house, I was heading to the garage when I came to the realization that I have a large collection. I began to study it, and I was very surprised to discover how much of it was specifically conceptual art and Arte Povera. I had completely forgotten about that over the last twenty years. I simply hadn't thought about it.

How many units did you have?

Lots. And when I understood this, I began to collect... I perceive the collection as a mosaic in which my creative part is to create a kind of “picture of time”. I began to intensely look for and buy the missing links or pieces. In 2000 I stopped. I organized large exhibitions in several museums, and then I gave my collection to the National Gallery of Germany and the Hamburger Bahnhof.

Did you give away the whole collection, or only a part of it?

All of it. At first, I sold a third of it, I gifted the second third, and the last third I loaned out to them – I left it there like a deposit. But at the beginning of last year, I gave them the whole thing as a gift.

Why did you make the decision to give your collection away to the museum? Was it because that would be the logical next step?

Yes. I think it is nice that as a collector, one can have all these things... but now I am seventy years old and I have to bring things to order in terms of my family, my belongings and so forth. In addition, as a collector, one has a large responsibility to art. In my opinion, the best thing one can do with one's collection is give it to a museum.

Was this an easy decision to make?

For me, yes. Maybe it wasn't so easy for my children. But besides the collection, I also have this large archive project. Truthfully, what I'm working on right now is a job without end.

You mentioned this “mosaic” approach – when you gave the collection to the museum, was it complete?

Yes, it was complete. It was done.

As a collector, it has always been important to you to document all of the aspects of an artist's activities – from a simple sketch to postcards, letters and so on. Why is this?

I'm not religious, but in art there is something to do with religion. When you say: “This is a work of art”, that is really only a statement. I can either believe it or not. In a sense, this is a religious attitude. I am an atheist and I have never been fascinated by all of these things dealing with the “auras” and “energies” of things; I have always been interested in the process itself. How a specific piece of art came to be. As well as taking into account all of the constraints instilled by society and so on. Art is always a question for me.

Have you been able to find answers?

Sure. That's why I bought art. But I think that normally, art is only art when there is a connection between it and the viewer. They are connected to one another.

Sol LeWitt: Incomplete open cube (No. 7-15/1974/1990), 1974/1990. Sammlung Marzona. Photo: Staatliche Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart / Peter Neumann

Sol LeWitt once said: “All intervening steps, scribbles, sketches, drawings, failed work models, studied thoughts, conversations, are of interest. Those that show the thought process of the artist are sometimes more interesting than the final product."

Yes. It has been my intention to show this process. And Sol was a very good friend of mine.

How do you remember him?

Perhaps you know this story. I have another large project in Italy. A sculpture park in the village of Verzegnis, on my family's property. For the last 35 years, I have been inviting artists to go there and make works specially for this spot. And not only in the park, but in the buildings as well. I had bought a large wall drawing from Konrad Fischer – a long time before I started this project. I wasn't sure where would be the best spot to put it, so I called Sol and asked him to help me find one. He came with his whole family. Sol's daughter, Sofia, who manages his property now, wasn't even of school age yet, I think. The kids played in the garden, and the women went shopping in Venice or Udine. During this time, Sol just sat in the salon, reading and listening to music. For the whole two weeks. Finally, the day before they left, he told me that he had found the ideal place – but he wants to make a triptych. I agreed and he was very happy. He went back to Spoleto and called me a week later: “Egidio, I am so happy, but you also have that long wall with five windows. I would also like to create some wall drawings.” And that's how one work at first turned into three, and in the very end, there were eight. Another week later Sol called me again, saying that on his last visit he forgot to speak to me – he said that I am also in need of an outside sculpture. “Two models are already on their way. Try them,” he said.

And you didn't have any idea what you were being sent?

I didn't. But I bought also these two sculptures. One is currently in Verzegnis, and the other is in the sculpture garden of Kunsthalle Bielefeld. In the end, I thought to myself that this is a rather large purchase – when I added all of this to the first drawing I had bought from Konran, it would amount to a significant sum of money. But Sol didn't accept anything from me. He was so happy that someone was willing to follow his hopes and ideas. He was a very special type of artist. There's another story which is not so well known. Sol worked with many galleries – even very small ones; with people that he liked and that he had selected. Among these there were both very influential galleries and galleries that were virtually unknown. He didn't focus only on the loudest voices. And every time he had an exhibition, he took half of the money that he had made from selling his works, and left it with the gallery – by buying the works of emerging artists. For example, he was the first one ever to buy a work by Tomass Schutte – from Schutte's first exhibition at Konrad's gallery. Sol had a huge collection.

Bruce Nauman. Truncated Pyramid Room in the Art Park of Villa di Verzegnis. Photo: Marcus Schneider

Were you very close friends?

Yes. And the system with which he worked was kind of reminiscent of the old European Bauhütte tradition, in which under the guidance of a master, a group of people would build all of the large cathedrals of the Middle Ages. That's also how Sol worked – he had a group of people who executed his wall drawings, models and prints. It was his own kind of Bauhütte. It was very fascinating; I don't think the Americans ever realized this.

How did the idea for the sculpture park come about?

Actually, that was Konrad Fischer's idea. About three or four times a year, he would come over to pick mushrooms and drink wine. And one day he said – Egidio, you have so much land, you have three houses; you must invite artists. So I agreed and he immediately placed a call from my place in Italy to Bruce Nauman. And three month later, we had this gigantic pyramid.

Have all of the artworks been made specially for the park?

Yes, according to the specific location and situation. Even in the house, they are all wall drawings. Nothing has been framed, nothing has been painted. Everything has been done in correspondence with the situation.

Richard Long. Tagliamento Stone River Ring, 1996. Photo: Marcus Schneider

And the process in which you work with the artists – has it always been the same? They come here, stay for a while, you discuss things...?

Yes, they would come here, we'd speak at length, and they would come up with suggestions. There were some things that I had never even thought about. There's always great competitiveness among artists. The first piece in the park was this large pyramid by Bruce. And then they started to arrive one after another... For instance, Richard Long created the largest of his works, up to that point in time, right here (Tagliamento River Stone Ring, 1996). All three of us – Richard, Konrad and I – worked for three weeks until we had carried all of the rocks from the riverbed to the garden, so that Richard could made his large circle. We even rented a small tractor to aid in the process.

Do you continue to add more artworks to the park?

Yes, except now I have had to move on to the next generation, since most of my friends are either old or dead. So, I have begun to work with the new generation. And that is a new experience again.

Sol LeWitt once said: “Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists.” What is it about conceptual art that fascinates you?

Looking back over time, in the middle of the 60s there was a lot of discussion about art, and these discussions were often based on political ideas. I liked this attitude. Especially because I leaned very much to the left in my youth. At the same time, of course, there was pop art and fluxus, but they were the kids from the other side of the river. I was also very much influenced by Konrad and what one would call “the intellectual aspect” of art.

What is your opinion on beauty and aesthetics in art?

As I said, the first thing I bought was a painting by Robert Ryman. It was all white. My family was pissed-off. They thought I was mad to spend 300 dollars (at the time, that was a lot for a work of art) for “nothing”. I'm fascinated with buying ideas, not artworks. My whole life long, this has been behind all of my thinking.

Richard Long: Autumn Turf Circle, 1998. Sammlung Marzona, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Photo: Nationalgalerie Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart / Marcus Schneider. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

Beuys once said that anyone can be an artist.

Back when I lived in Düsseldorf, we had a very good relationship. I have some of Beuys' drawings, but I have never bought his large-scale works. He had the status of a kind of religious figure. To many, he was like a shaman, a preacher. I wasn't rather fond of that. On the other hand, I was fascinated by the large installations that he would make. However, right from the start I wondered about what will happen to them once he is dead. When I look at them today, they look like junk. Because as soon as you move any of his works five centimeters either in one direction or the other, they are ruined. And when I see how Beuys is being exhibited, for instance, at Dia:Beacon, Kunstmuseum Basel or anywhere else, I get this feeling that ever since he died, his works have been destroyed. Because only Beuys himself had the necessary sensibility to make his installations function. The same goes for minimalistic art. When the Tate Modern was opened, in the center of the museum there was that huge space with the minimalistic art collection. That was a complete misjudgment. It looked like an IKEA store. The layout was so bad and strange that it completely ruined the idea of the artworks. To exhibit this kind of art, the essential thing is space.

What do you think was behind the Beuys phenomenon at the time?

I don't even know what he was really like because he was always telling stories. And many of them were untrue. For instance, how his plane had survived a crash. That was a legend. He was a storyteller. Nevertheless, he was a big artist. His ideas strongly influenced the new generation. He was also quite closely associated with “the other side” – the fluxus people. In contrast, I was more influenced by the pure, hard-core minimalist artists.

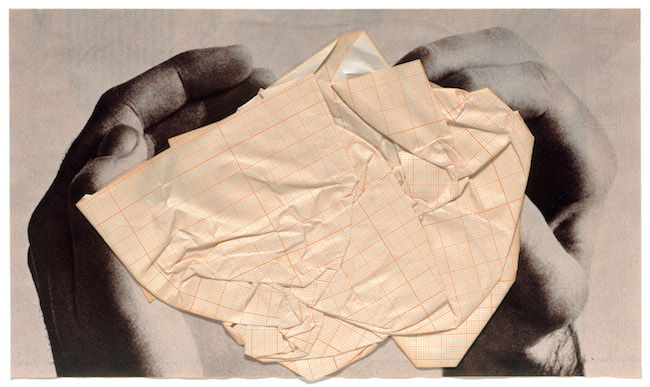

Giulio Paolini: Ohne Titel, 1973. Sammlung Marzona/ Photo: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie im Museum für Gegenwart / Volker-H. Schneider

Your collection also has a huge quantity of postcards and invitations that artists sent out for their exhibitions. Why has it been so important to you to amass all of this and preserve it?

Because these cards, much like the artist's sketch- and notebooks, are also a work of art. As I said, I'm interested in ideas and also in the statement that art makes. From the beginning of the sixties until, let's say, the end of the seventies, a large part of these cards, artist books, posters and other materials were very important artworks in themselves because they were statements on the art. And this is what has been left. Because all of the shows – those were only ideas. I had realized this from the very beginning already, and I was always very enthusiastic about this kind of material. I also have a large collection of manuscripts written by artists, as well as letters and other materials that relate to their work.

Is a letter written by an artist also a work of art?

Yes, that can be an artwork. I, for example, have many postcards from Sol LeWitt. He also had small drawings, notes on concepts, statements and text pieces... They are all artworks.

What makes something a work of art?

As I said, it is the relationship between the piece and the person. For me, only this is art. You can say this is an artwork. Anybody can say that, but they are just making a statement. The reality of it comes when I accept it as an artwork.

What if you, for example, accept this table as being a work of art, but I don't. Is it a work of art?

For me, of course it is.

And for me?

For you – no.

Does a collector have the gene for hunting?

In my opinion, today's approach to collecting is starkly different than back when I started. There were only a few collectors in Germany back then; a bit more in Belgium and the Netherlands. Some in Switzerland as well. When the first art fair in Cologne took place, 14 galleries participated – all of the artists and collectors came. It was like a family get-together.

Today I'm not very happy when I see all of these big collections. They have been created with big money. They are all buying only “blue chips”. 90% of today's collecting is focused on, let's say, 20 names. And for me, this kind of collecting is not collecting. It is making an investment.

Why has this happened?

Because the art market is so strong. It's worth a lot of money now. In my time, money was in second place. It was important, but not like today. Today everything is based purely on money and speculation. And investments. In my opinion, it's become a complete misunderstanding of art.

In the long run, has the relationship between artists and collectors also changed?

Collecting is quite popular today. The art market is big. For instance, there are about 600-700 galleries in Berlin now. They come and they go, but the numbers stay about the same. 25 years ago, there were 25 galleries in Berlin. Think about it – just 25 years ago! And now there are 20 times as many.

As far as I know, some of them are really struggling to stay on their feet.

Yes. I see two problems in this situation. One is speculation – increasingly hiking-up prices. The other is inflation. There is too much of everything – too many galleries, too many artists. A kind of inflation of art is the governing force right now. Marcel Duchamp said, I think in 1954, that the commercial system will destroy art.

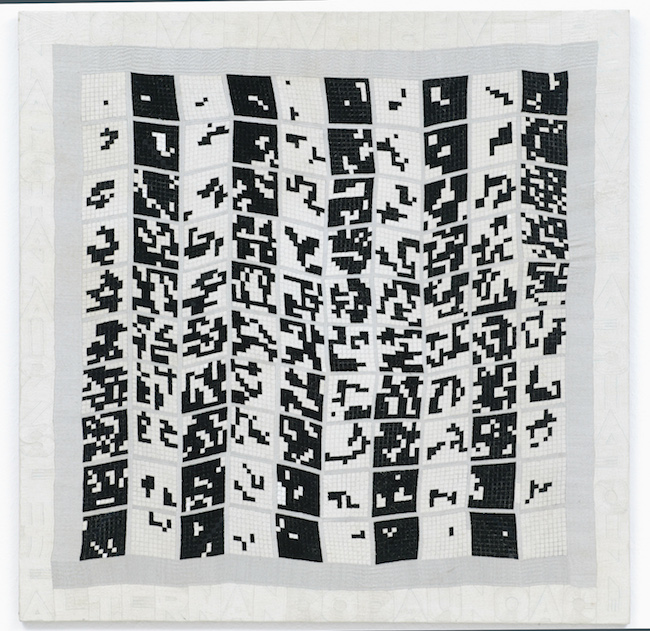

Alighiero Boetti: Alternando da I a IOO, 1979. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Sammlung Marzona. Photo: Staatliche Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart / Jens Ziehe. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Do you think that this has come true now?

Yes, I think that we are seeing this in real life now.

Going back to those 20 “big names” in art – what do you think has made them get to where they are?

It has to do with market forces and with the power of the galleries; and the dealers. This is very new because 25 years ago, and even earlier, the art critics had great importance. At that time, the art columns in the newspapers were, for the most part, of a very high level. Nowadays, the information they contain is mostly about the market – prices and transactions. That makes a big difference, and the result is fertile ground for high prices and speculation. It's a global game now.

In your experience as a collector, have you ever overpaid for an artwork in your quest to acquire it?

I have sometimes spent large amounts of money on art, but I have never had the thought that, perhaps in the future, I could make money off of it or realize some other gains. That's why I gave my collection away as a gift; because I feel I have a responsibility to both art and society. However, I believe that such values do not exist anymore. The current art market is only a game of power and speculation. I am sorry to have to say this, but this is based on my fifty years of experience. If we look at it from afar – we have been living in the new century for 15 years now. During the transition of one era to the next, usually stark changes can be felt. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, art experienced a liberation that presented itself in different ways in various European countries. That was a sharp change in direction. The whole of the 20th century was based on “-isms”: futurism, constructivism, expressionism, surrealism and so on. This continued also after the war. And then it came to an end – with fluxus, minimalism and pop art – all of these movements of the 60s. There wasn't anything after that. Right now we have a chaotic situation of art inflation. In addition, we're living in an era of information overload. And all of the young artists know it – everything has been done. They try to use and interpret these ideas in new and ironic ways. I think (and these are only my ruminations), that perhaps, information could turn out to be the death of art. Sometimes I feel this; because everything has already been done.

My son is an art historian, and he spent a long time in America as a curator. Now he is back, nearly ten years already. He has had his own gallery for a year now, and when I was sitting with him and his generation of artist friends, they were are talking about strategies. When I see young artists now, they mostly talk about strategies, and not about ideas anymore. In my time, they were fighting for their ideas.

What do you think would have to happen for art to regain its true value?

(Laughs) I hope it will not be a third world war that will destroy everything, and only after that happens, do they begin to come up with new ideas. But maybe this is cyclical.

Having given your collection to the museum, what is the main thing that differentiates a museum collection from a private one?

In many countries, including Germany, there have been new museums established in the last twenty years. We already spoke about the market. A large part of art has become very expensive, and the museums simply don't have the money to buy it. Because of this, the link between private collectors and museums has become very crucial. Truthfully, I don't think it's the best solution, but that is the reality of it.

Is it not the best solution because collectors force their own artists upon the museums?

Yes; they have their own interests, ideas and strategies. In order to not succumb to this influence, the museum should really have the final word. Art historians – the responsibility must be based on art history.

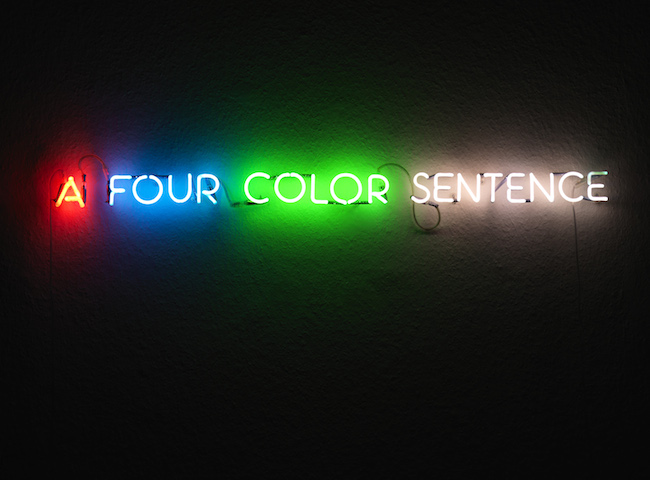

Joseph Kosuth: A Four Color Sentence, 1966. Sammlung Marzona. Photo: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart / Jens Ziehe. © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2014

At the same time, there's the constant rumor that if a collector loans his pieces to museums and institutions, then that raises the market value of the pieces in question. Is this true?

I don't think so, but of course, someone could be doing it. But I think that's a really stupid idea – to think that a collector has loaned out a piece for a museum exhibition only to raise its market value.

Nevertheless, there are very few real collectors today. In Berlin – Alex Haubrok; in Hamburg – Harald Falckenberg. He's of the old stock – a seasoned authority and a true art collector. He likes art and he knows a lot about it. And then there's the Brazilian, Bernardo Paz; he's completely mad. His family owns mines and he keeps selling them off so that he can invest in new art projects. There still are people like this, but unfortunately, just a few.

Several collectors we've spoken to have admitted that to them, their collections give them the opportunity to live another, a kind of parallel, life.

I think that collecting has a lot to do with the fact that we have a limited life; one could say it's a way to fight against death.

By leaving something behind, it will continue to exist, and in a way, you will still exist as well.

Exactly.

Was that also one of the reasons that you decided to give your collection to the museum?

No. That was the feeling of responsibility. It has nothing to do with myself. It is connected only to art. It had to be in a better place, and the collection had to stay together. In making a collection, one is also making an imprint of time. By collecting, I understood that this process – finding and combining things – is actually like a new painting. A new artwork or a new composition.

So then a collector is also an artist, in a sense?

No, not an artist. I've never had the feeling that I am an artist. More like a composer, architect or film director. If I see something that speaks to me, I still buy art. For example, I recently bought a piece by a very young Russian artist. Because there was something there that I had never seen before. To me, art is still a question to be answered.

Daniel Buren: Une peinture en douze éléments. formant une architecture, 1975. Stoff, bemalt / Fabric, Marzona. Photo: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof - Museum für Gegenwart Bild-Kunst, 2014

When I tried to contact you for this interview, I was surprised that you don't have an e-mail address.

I don't even have a computer. You know, when the fax machine appeared in the 70s, I perceived that as a catastrophe because it destroyed our culture of writing by hand. I like to write letters by hand, and I like to receive letters from my friends, from artists. But that time has gone. We are increasingly destroying our culture. Just to be faster, greater.

But those are the times that we live in.

Yes, but it's a completely misguided idea. I have never used a computer, nor have I ever written a text message on a phone.

But how then do you communicate with museums in the 21st century?

Through letters.

* The Getty Research Institute in California. Jean Paul Getty (1892-1976) was an American industrialist and art collector.