Striving for Absolute Harmony

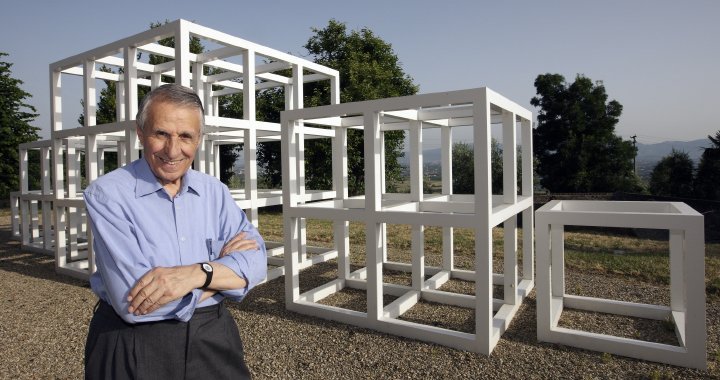

An interview with Italian art collector Giuliano Gori in Santomato

17/12/2014

Fattoria di Celle, a park of site-specific outdoor art in the small town of Santomato half an hour's drive from Florence, is one of Europe's most exciting and impressive phenomena in contemporary sculpture. It is often called a sculpture park in the media, but its creator and founder, art collector Giuliano Gori, emphasises the significance of site-specific and environmental art.

Even though the geographic location of Fattoria di Celle – Tuscany – seems like a complete epicentre of tourism, the park is not located on standard tourist routes. In fact, probably very few casual visitors enter the grandiose villa gates. Most visitors are in the know, people who have deliberately chosen this destination. The first object they encounter is Alberto Burri's five-metre-tall bright red installation Grande Ferro Celle, which was erected right next to the main road to Pistoia in 1986 and has become a favourite landmark to describe the way to Celle. The light and airy giant sculpture by Burri, which frames the surrounding landscape from various viewpoints and is also featured in the park's logo, serves as an introduction to the four-hour tour into a fascinating world in which the synergy between art and nature has reached absolute harmony. Gori himself, who began collecting art at the age of 17, says, “This art has not been created to make only one individual person happy; this is not art that you simply place in your home and it belongs only to you. This is art that incites discussion, and therefore it's important to make it available to the public. The public at all levels, from specialists all the way to people who are just interested in what we are doing here.”

Gori's collection contains not only these on-site environmental works of art but also many other pieces of artwork – paintings, installations, sculptures – some of which can be seen at the close of the tour. But it is precisely the park (opened in 1982 with 15 on-site works of art, nine in the park and six in the villa's main building) that is open to the public free of charge and best embodies the essence of Gori's philosophy.

Luigi Mainolfi. For Those Who Fly, 2011

Fattoria di Celle is a legendary property that once belonged to Cardinal Carlo Agostino Fabroni and passed into Gori's hands in 1970. In the mid-19th century the local architect Giovanni Gambini created a six-acre English-style garden on the property according to the wishes of the owner. Several tens of artworks have been sensitively integrated into the garden (and also in the villa's various buildings). The artwork lives in complete harmony with the surrounding trees, hills, meadows, waters, fog and old buildings – the villa itself, the aviary, the tea house, the bridge – together creating a feeling that the presence of contemporary art here is just as natural as the olive trees emerging out of the landscape on a foggy autumn morning. Here, the nature, architecture and ancient artefacts do not serve merely as a backdrop to contemporary art; they are not simply the “white cube” in which to display the art but an actual ingredient of it. When, after the four-hour walk, you've come to the last exhibit – a green bench on top of a roof titled For Those Who Fly, Luigi Mainolfi's dedication to Gori's deceased wife – you clearly understand that here the past and the future, the otherworldly and the mundane, art and nature have bonded into a single whole. Ideal beauty and romanticism are not concepts often found in the contemporary art lexicon, but at Fattoria de Celle their presence is unmistakable.

As is common nowadays, I searched your name on Google before we met. One of the first results of the search was Andy Warhol's portrait of you. How did that come about?

That was an unforgettable experience. Warhol had arrived in Italy to visit his friends, who told me, “Hey, we just talked about you with Andy. Maybe you'll come over to meet him?” And so I ended up at a crazy party. Never did the thought cross my mind that I'd have a portrait done of me there. Warhol simply took photographs. There were lots of beautiful, young women there. One of them stated that she hated life and was going to commit suicide. I tried to convince her that such a decision can only be made once in a lifetime. She was standing in a window, and I tried to get her back inside. That's the kind of evening it was when that photograph was taken. I had no idea that a piece of art like that would be made later. If I had known, I would have brought along other members of my family. Warhol was a very nice, sincere person.

Magdalena Abakanowicz. Catharsis, 1985

I understand that relationships with artists are very important for you. Why is that?

You could say I turned to site-specific art also because I wished to be in closer contact with artists. Artists had become completely alienated from the commissioning process, which meant that they had no relationship with the art consumer. They had immense freedom; they simply created and put on the market whatever they wanted to. It was a challenge of sorts for me to offer them specific conditions in relation to a site and space in which they could then enjoy complete freedom. And it would be completely independent of market-dictated conditions.

There are art collectors who choose not to get to know the artists who have made the works in their collections....

I am completely convinced that a collector must do so. I do not understand those who state they do not want to meet the artist privately. It's shameful to be so far from the very source of creativity.... If you like the creative process, you want to know all about it; you want to know where it comes from. Over the past several decades we've seen the process in which art and the collector have distanced themselves from each other. People just buy art and put it on their walls. That's in complete contradiction to my conviction about what my collection should be like. Fattoria di Celle is absolutely bonded with the artists. Each piece of artwork here is the result of that philosophy. It is very important to know the artists as people.

Anne & Patrick Poirier. The Death of Ephialthes, 1982

What inspired you to create a park of site-specific art?

There's a difference between art that is located in the place it's meant to be and art that is simply located in a museum. When you go to a museum, you see lots of separate pieces of artwork that have been removed from their contexts. If you could imagine what they'd look like in their correct context – an ancient castle, a church – it would be clear that they look incomparably more powerful and convincing there. Time, the design of the space, the environment – it's all a part of the artist's concept. You can visit all of the world's museums and see all of the paintings that you like, but they'll never be as effective as if they were located in their original context. And that's a way of understanding how influential the experience of a specific environment can be. For example, take Michaelangelo's The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel – that masterpiece was created only for that specific site, and it would lose its meaning if it were moved anywhere else. And that's just one example of how important space and its features are. Such considerations have influenced my collection.

The conceptual foundation of Fattoria di Celle is based on beauty and the way in which you see a work of art. It was once quite a difficult task for an artist, having received a commission, to think about the space in which the work of art would be displayed, about the window that would let in light and illuminate the artwork, about how to take all of these conditions into consideration and create a harmonious composition of these components. But life for appreciators of art was very easy – all of the preconditions for successful communication with the artwork had been taken care of for them. Nowadays artists have complete freedom to create whatever they want, but the people who come into contact with these works of art, the people who see them, they have problems “reading” the art. It's confusing when Klee tells you, “I don't paint what I see; I paint what I feel. And it's your responsibility to find the codes to read it.” Creating artwork at Fattoria di Celle means that the artist must be here and must take into account all of the preconditions of this place. Similarly to how it happened in earlier times.

Jean-Michel Folon. The Tree of Golden Fruit, 2002

How do you get them to agree to your dictated preconditions, how do you get them to almost completely change once they've arrived here? For example, Richard Serra made his first piece of art out of stone right here.

I ask the artists to involve the surrounding area in their artwork, to make it a part of their artwork. And that's the real key. This isn't just a space to display any kinds of artwork. If the artist understands that, if he is captivated by this task, then everything else turns out. The artists I invite use today's language of art, but they must also keep their focus.

Which work of art at Fattoria di Celle would you call the heart of this place? I've heard that The Tree of Golden Fruit is a very emotionally important element.

I don't want to single out just one work of art. But the work you mentioned is a symbol of what I am trying to do here. It's located in the old aviary, inside of which trees are growing in their natural environment. And the artist Jean-Michel Folon installed a tree there whose seven “arms” offer water and food for the birds. It was so impressive that I was ready to remove part of the roof, because it was really very important that the birds could come and go as they pleased. And Celle as a whole is a story about freedom – it is a shelter, and it is a combining of art and nature into a single whole.

As I understand, the relationship between art and nature or, more precisely, the wish to allow them both to develop in a natural way, is particularly important to you. For example, Dennis Oppenheim's Formula Compound was damaged when a storm blew down a tree. But you decided to not touch it, to leave it be....

I think Folon's and Oppenheim's works are two different cases. The aviary is a symbol of Celle's collection, but when I think about Oppenheim's work, I think of a great drama. Because the oak tree that fell down was about 35 metres tall and undoubtedly a dominant feature in the landscape. Because of that, Oppenheim's work looked completely different than it does today. This awful storm, which uprooted many trees, was a very dramatic experience. I therefore almost had the feeling that a part of this artwork had died. But now I've discovered that little, young trees are growing next to his work of art; trees that have sprouted from the dead tree's roots. And that means a lot.

Anselm Kiefer. Cette obscure clarté qui tombe des étoiles, 2009

Isabelle Maeght, whom Arterritory recently interviewed, said that the room in which Anselm Kiefer's work is exhibited used to be her bedroom.

Yes, that's so.

Why did you choose to put Kiefer in that particular room?

Every piece of artwork here has its own story. I could write several books about these stories. The piece of artwork you mentioned is about two people who like each other but cannot find one another and be together for years and years. When I began creating my site-specific art collection, I went on a trip to visit Kiefer and talk to him about making an artwork for Fattoria di Celle. But, no matter how serious our agreement was, nothing happened for years. But I never forgot that I wanted Kiefer to be a part of Celle. A few years later I was in Kiefer's studio again with the same offer. And he said no, because he needed a completely specific context. If I was unable to provide him with such, he was unable to do anything and I would not get my artwork. Then I told him to come visit me and we would look for what he needed. And that's how we got to this spot. Kiefer said he thought we had found the right space, but it would need to be modified; the floor needed to be lowered by 20-25 cm. The goal was to make this space similar to that in which his artwork had been displayed up until then. And so we reconstructed the building to meet his specific needs and guidelines. It's a very special room with a very high ceiling.

Dennis Oppenheim. Formula Compound, 1982

You've been in the art world now for over half a century. What has changed in the atmosphere of the global and Italian art world compared to when you began collecting?

In today's globalised world you can't really talk about, for example, Italy's art scene or that of any other country. 50 years ago it was hard to get information about what was happening beyond our national borders. The 20th century was a period of such surprising change, everything changed extremely quickly. I think, if you want to be informed, knowing and take part in today's art world, you need to be educated in philosophy, literature and a great variety of fields, even fields that differ greatly from one another. You need to follow what's happening in the world. And if you don't do so, then you are in a way confined and limited in your perception of art.

Artists today use such different instruments and are so different themselves, that the art viewer needs to work in order to understand a work of art. And that's the first step. Maybe you love this piece of artwork, maybe you do not agree with the ideas the artist is expressing, but the first step has to be precisely this desire to understand it. If you can understand it and love it, that's the best thing that can happen to you. But if you distance yourself from the work of art, you will never be able to fully understand it. Art is a part of life, and one must live it fully.

Richard Serra. Open Field Vertical Elevations, 1982

Isabelle Maeght calls you the last real art collector in today's world. I've heard that you don't like calling yourself a collector. Then what are you?

I'd call myself a non-profit cultural entrepreneur.

Your CV states that you began to take an interest in art in 1947. So, you were just 17 years old. What was your first purchase, what inspired it, and why are you still buying artwork?

The second half of your question seems much more interesting to me. There's no point in asking yourself why you began doing something. But it's very important to ask yourself why you continue to do it. I was really very young. I still have the shorts I wore back then, the kind all of the boys wore at that time. I met an artist, and he changed the direction of my life. But if I had met a stamp collector, I may have possibly focused on something different. So, a big part of my beginning was a matter of chance.

Regarding the more essential part of your question – why I'm still doing it.... When you reach a certain point in your activities, in your life, you realise that you have something to say to everyone else. You want to talk, to discuss and not just be an observer. You enjoy communication itself.

There are art collectors who stress the significance of art in their everyday home life, and then there are collectors who cannot be together with art day in and day out. When asked by her friends why there were no cupboards or wardrobes in your home, your wife once said that it was because her husband needed space for artwork. How important to you is this daily contact with art?

After all of these years, I maybe sometimes feel like a prisoner of my collection. But a very privileged prisoner. And even if I'm far away from my collection, I know I will return and it will be here. Living together with works of art – it's a give-and-take situation.

How important for you is the enjoyment of art as a form of meditation, the energetic relationship with a work of art?

Many of the artists who have created works of art for Celle have spent a year, two years, some even three years here. A work of art is something that develops over time, and artists are beings with their own energy fields. The works of art, of course, have accumulated this energy from the artists who made them. When I come into contact with these works of art, of course, I feel all of those energies that hovered in the air when we were all here together. Of course, it would be wonderful if others could feel this as well, but I think that is nearly impossible. Even if you're the best art critic in the world, you'll never be able to reveal the emotional layers of living together that have developed between the artist and commissioner as they work together on a project. For me, this flow of energy is very special.

Everyone has their own individual experience and very direct feelings when they come into contact with art. I've always tried to see as much art as possible in all corners of the world. When I find myself in front of a work of art that is called a masterpiece, I sometimes become very frustrated because I don't feel anything. And then I start to think that either the work of art is a forgery, or else I don't understand it. It's very important for me that a work of art inspires me or makes me excited. Otherwise it's not a good feeling. Each of us is searching for something in art. Sometimes contact is established quite instinctively, and sometimes it's a pragmatic process. For me, it's important that art inspires me.

Robert Morris & Claudio Parmiggiani. Melencolia II, 2002

I know you don't want to talk about the relationship between art and money. But it's a very hot topic in today's world.... And art collectors are people who influence this drama themselves. Do you, for example, take an annual trip to Art Basel, the collectors' Mecca?

I don't go to it. Of course, I don't want to talk about it at all. But fashions, art fairs and other such things are not phenomena I associate with art.

A 2012 issue of Sculpture Magazine wrote that you are now planning to turn more of your attention to things other than Fattoria di Celle. Does that mean that this project has ended?

The site-specific art collection is always in a state of development. For example, in the next few months we will open the chapel door created by Claudio Parmiggiani – that will be my new acquisition. We are continuing to move forward. Of course, I am involved in many art projects, especially those that take place in the surrounding area.

For example, the Pistoia hospital project?

Yes, that was a big and actually quite original project, because the artists were invited to not only decorate the rooms, but from the very beginning they participated together with the architects in the process of creating the interior design. It was a long process – the city was building this dialysis centre for five years.

Your children are also art collectors. How did you get them interested in it?

Yes, all four of them. I have a daughter and a grand-daughter with degrees in art history. But in no way did I spur them on. I only maybe integrated a little art into the places where they lived.

When the time comes, will they take over the collection?

I would like for everybody to be free of all responsibilities, as much as that is possible. I would like them to follow their own conviction and intelligence, not my decisions.