“Braque was my third grandfather”

An interview with Isabelle Maeght, art collector and shareholder of the Fondation Maeght

03/09/2014

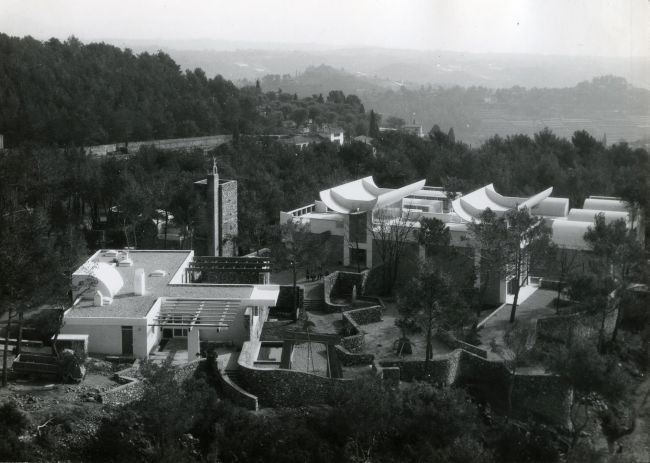

This year, one of Europe's most beautiful small museums, Fondation Maeght, is celebrating its 50th anniversary with an exhibition of the Maeght family's private collection. The Maeght Foundation was established in 1964 by Aimé Maeght and his wife, Marguerite. Aimé was one of the most influential art dealers, collectors and publishers of the 20th century, and the foundation he and his wife founded contains one of the most prominent collections of 20th-century art. It is also the first museum in Europe specifically designed to house works of modern art, based on artists’ grumblings about having to display their new oeuvres in churches and other inappropriate venues.

Marguerite and Aimé Maeghts at inaugural of the Fondation Maeght. Photo from Fondation Maeght archives

But the establishment of the foundation is also a testimony to the power of art. This site, on a beautiful hill surrounded by pines on the outskirts of the French Riviera town of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, was once the home of the Maeght family. The home was visited regularly by Henri Matisse, Alberto Giacometti, Fernand Léger, Joan Miró, Georges Braque and other prominent artists who were friends of the family. But this idyllic life was overshadowed by a tragic event, namely, the death of the Maeght's 12-year-old son, Bernard, of leukaemia. At the time, Léger suggested the grieving parents take a trip to America.

.jpg)

Fondation Maeght. Photo: Stéphane Briolant. Photo from Fondation Maeght archives

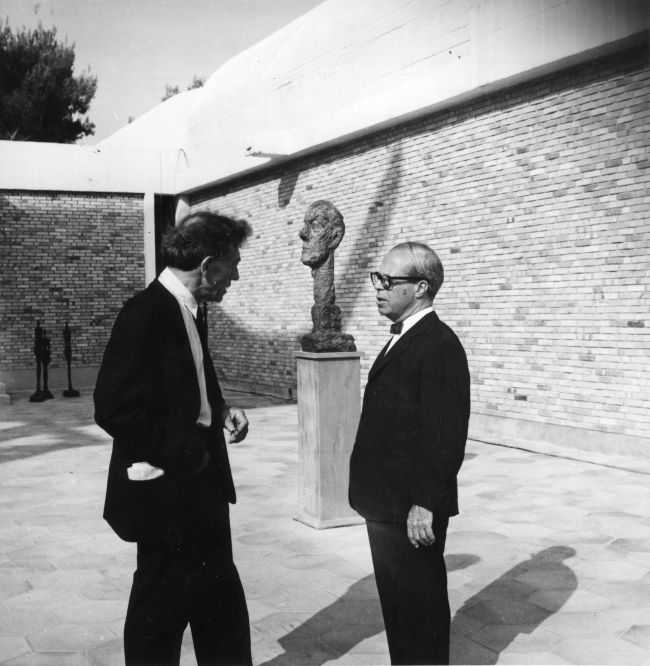

It was there, having been inspired by the Barnes and Guggenheim foundations and having been urged on by friends, that they decided to open their own art space and dedicate it to their son. The Maeght's wish was to create a modern, functional museum that would also fit in organically with the large Mediterranean garden; they wished for it to serve not only as a museum but also as a supporting institution of sorts for artists by offering them a space where they could freely express their creativity. The Catalonian architect Josep Lluis Sert, who had recently finished designing a studio for his friend Joan Miró in Palma de Mallorca, was invited to help in the realisation of the project. The architectural nucleus of the museum consists of interconnected one- and three-storey buildings. Due to the unique shape of the roof, some of the exhibition halls feel almost like a cathedral. It is symbolic that a small chapel, the ruins of which the Maeght family had discovered as construction began, was to become the centre of the nascent foundation. The chapel was restored and integrated into the whole architectural ensemble; the artists Ubac and Braque, also friends of the family, created the design for the stained glass windows. Separate spaces in the museum are devoted to Miró and Chagall, and a steel fountain by Pol Bury and a labyrinth by Miró can be found in the sculpture garden. Today, the family traditions are being sustained by the Maeghts' grandchildren and great-grandchildren, who are continuing to expand the museum’s art collection with contemporary works by 21st-century artists.

The Maeghts' son Adrien is currently the chairman of the administrative council for the foundation; Adrien's daughters, Isabelle and Yoyo, are also on the board. Isabelle is also in charge of the family's gallery in Paris, and her brother, Jules, manages the publishing business and Maeght Editeur, which is one of the best known printers of lithographies and etchings in the world.

The day I visit the Fondation Maeght building to meet Isabelle Maeght, there are so many visitors to the anniversary exhibition that the only quiet space Isabelle finds is in the kitchen. As we drink coffee, she smokes one cigarette after the other and slightly resembles Peggy Guggenheim. She calls Georges Braques her third grandfather.

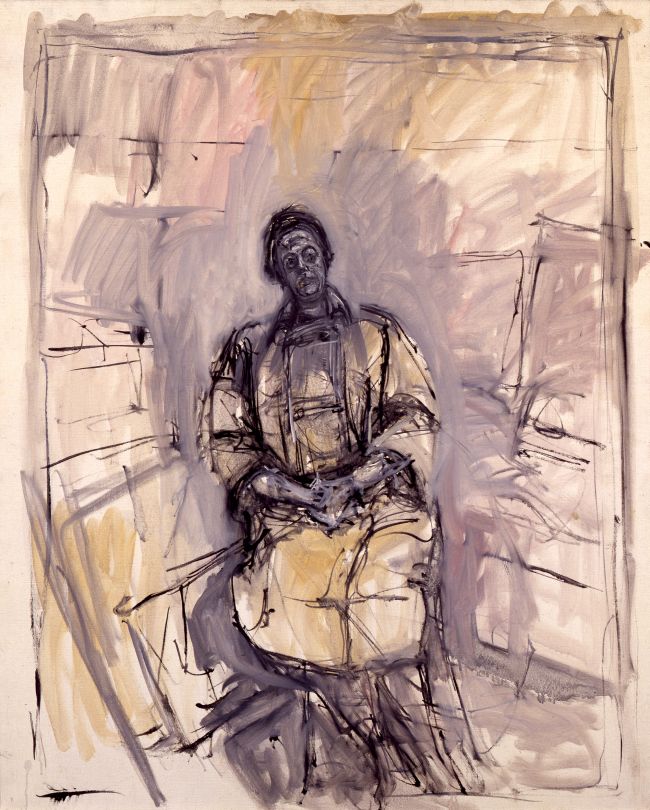

Alberto Giacometti. Portrait de Marguerite Maeght, 1961. Photo: Galerie Maeght © Succession Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris + ADAGP, Paris), 2014

Art and art collecting is in your genes. What is it like to have been born into a family that people refer to as the First Family of Modernism Art?

Collecting art is a natural and also a very essential thing for me. We are also dealers, which would normally mean that everything is for sale. But our family owns works of art that will never be sold. Under no circumstances. Maybe you noticed that Giacometti's The Nose is being shown at the anniversary exhibition. It's a plaster sculpture that my father gave to the Centre Pompidou in Paris as a gift. Many collectors coveted the sculpture and offered unimaginable sums of money for it, so my father decided it would be best to give it to a national museum, thereby ensuring that it would never be sold, no matter what dizzying price were offered. These are crucially important works of art both for art history as a whole and also for our own family. For example, a portrait of my grandmother created by Giacometti – that will never be put on the market. Also, a series of small drawings, because they remind us of some wonderful moments: a lunch, time spent with friends and so on. They're not just chef-d'œuvre; they are also memories and emotions. I think that's very important.

What do you consider the main lessons of your childhood, a childhood spent together with the genuises of 20th-century art?

I learned not only how to add pieces of art to a wall and how to live with pieces of art, but also how important it is to look. How very important it is to go inside the work of art. Not only to say, “Wow, this is a beautiful Matisse or Braque.” It's also important to know the artist's status and what he himself thinks about his work of art. Lydia Delectroskaya and I once published a book; she was Matisse's model and had documented the creation of a painting with daily photographs. In essence, the progress of every painting. When the book came out, Matisse's grandson Claude said that this was the first book devoted to Matisse in which he was able to understand something more about his grandfather. Because through this process and progress it's possible to see Matisse's genius. It's not the same as just looking at the result; it's also understanding how it came into being and why. With joy, with sorrow. It's different every time, and that's very important.

Today, it's important for me to add work by artists of my generation to the collection, artists that my parents or grandparents never represented. It's very important to buy things I like, things I love. If a certain artwork generates special emotions inside me and I am able to buy it, I do. It is especially important to work with young artists. Also in the print shop that we own, it's important to help artists create something special.

Alexander Calder and Joan Miró, 1969. Photo: Jacques Robert. Photo from Fondation Maeght archives

In a way, that's what your grandfather used to do. He basically inspired artists, not only financially but also creatively.

My grandfather was a lithographer. He ceased being a gallerist, but he kept his print shop. My father expanded this wonderful print shop and we – my brother, I and my son - are continuing it. I always say: ink is in my blood. Miró always said that print was very important to him because it meant freedom. It helped him to create sculptures and new ideas about them. Because print is a medium with which you can immediately see the results. Over the years, we've printed more than 3000 lithographies by Miró.

When Miró was 75 years old, your father gave him a special typography press as a gift.

My grandfather built this big press, and when it was ready to be used, Miró was so happy that he decided to sign it. And he named it in honour of this wife, Pilar, and signed it “Miró and Grandsons”. We don't consider it a work of art because it's still in use. Every summer it is dedicated to three young artists, and that's such a joy! Because if we gave it the status of a work of art, it would die. But it must live, it must continue. Miró was always very happy to meet young artists and talk with them. For us, Miró was as important a person as Léger and Braque. I loved Mister Braque.

You've said that Braque was like your third grandfather.

He was a wonderful person. He loved me as his granddaughter. I was the only one who was allowed to enter his studio. No one else was allowed there, except my grandmother, grandfather and me. Of course, I was very proud. You can imagine.

What did you do there?

I just sat there and talked with him. I was eight when he died. I was very young, but for me it's still alive. He was so beautiful. Very tall, with his white hair and grey-blue eyes. For me he represented something strong.

Like an ideal man?

Yes. Miró was something different. Braque always came to our house in the wintertime, but Miró came in the summertime. It was a different way of living together. In wintertime you're by the chimney, you're singing and talking. In summer you walk around the garden and just look at stones or whatever. For me, I've never collected pieces of art for a price; I collect pieces of art for what they are. Because they touch me as art. For the emotion they bring out in me.

Do you remember the first work of art you bought yourself?

I think it was a small Bonnard drawing. Because it was so sweet. It was a drawing with a flower. I was 20 or 22 years old, I don't remember any more. It's impossible to explain why. I don't know if other collectors are able to explain. I can't. The only thing you can explain is that you like this work of art and you want it. And then, either you are able to obtain it or not. And that's often what happens. Then it's frustrating, but that's natural. In French, there are two words you can use for “collecting”: collectionner and amateur. A collectionner is someone who collects things; he has many such things and he doesn't worry too much about whether what he collects is good or bad. Amateur includes the word “love”. I prefer lovers to collectors. It might be a book or a photograph.... But for me, it's important to be touched by the work. I know the foundation's artwork like no one else in the world. But I always stop in front of the artworks, even though I've known them for already 50 years. I still enjoy them very much. It's hard to explain, but these are very special emotions.

Alberto Giacometti and José Luis Sert. Photo from Fondation Maeght archives

Which pieces of artwork in your collection mean the most for you?

The portrait of my grandparents made by Giacometti. Several works by Matisse, Braque and Miró. You know, it always depends on the situation. There were two pieces of artwork my grandfather did not wish to sell. But, in the end, he sold them because he knew the collector very well and was convinced that these works of art would never again change hands and would always remain in the same place.

What do you think is your role and responsibility as an art collector?

There are two collections. The foundation's collection, which will never go up for sale on the market. All of the works of art that belong to the foundation will remain in it forever. And then there's the Maeght family collection, which can change. Sometimes my father has sold, for example, a very good work by Léger in order to buy one that is even better. The collection must rotate; in addition, our own taste also simply changes. Yesterday it might have been Bonnard, but today it's Miró or someone else. Also, we're constantly adding works by new artists to the collection. The foundation's collection, too, which began with Bonnard and Miró, is now continuing with works by very young artists. That's normal. Some museums have blocked themselves into a period. For me that's a pity, because it's not the role of a museum to say, “We're interested only in this period.” That's not fair, it's not good. We must go on, we must continue. Some people were shocked about the exhibitions in Versailles. I was very happy.

Are you talking about the scandalous Murakami and Koons exhibitions?

Yes, and to me that seems natural. At the time Versailles was built, it was the very epitome of modernism – why must modernity end in the 18th century? It must continue – with Murakami, Koons and others. There are very many places today – villas and castles – where history lives together with modernity very well. And no one can image saying, “I've stopped, I'm stuck in the 18th century.” Similarly, if Bobo (the Parisian name for the Centre Pompidou – U.M.) suddenly announced, “We're from the 1970s and that's where we're going to stay.” That's nonsense.

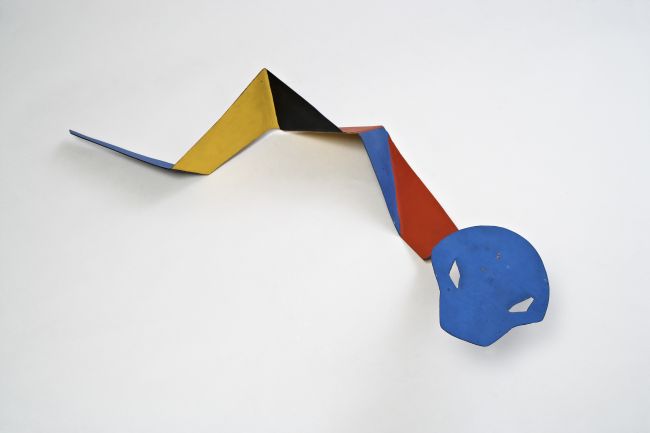

Alexander Calder. Photo from Fondation Maeght archives

The Guggenheim's potential project in Helsinki is currently stirring up great passions. Many people oppose it, especially from the local art scene, because they believe the entrance of a global museum brand can only harm the local scene. What's your opinion?

The Guggenheim has so many works by Monet. The collection is enormous. Why should the artworks be in a cellar? That's also our problem. We have more than 12,000 works in the Fondation Maeght collection and it's just normal that they rotate. We organise exhibitions in Italy, America, Stockholm, Helsinki, because we simply have too little wall space. The artwork must go outside. We own the most significant collection of works by Miró. Imagine if we announced that more than 100 of our sculptures were to stay in the cellar from now on. Poor Miró! That's why we organise exhibitions everywhere in the world, just so the collection is available. And if one of the serious museums asks us to lend them artworks for their exhibitions, we do it. We have no right to say, “No, because it belongs to me, it's mine.” Sometimes when I return home, the housekeeper says, “Don't worry, the Calder has gone to such-and-such an exhibition, and Miró has gone to....” For me it's OK, because I prefer that people see the works of art. Because even if only a hundred people understand the artist's work, it's good.

There was a large retrospective of Braque's work at the Grand Palais in Paris last year. Now it's going to Bilbao. We lent 20-25 works of art to that exhibition. A fantastic exhibition! I went to see it in Paris about four or five times, and I will definitely go to Bilbao, too. At the end of August, the Fondation Maeght team and I will go to the Matisse exhibition at the Tate Modern in London. I think it's also very important for the foundation's employees to understand how it all began.

Alexander Calder, Crinkly worm (animobile), 1970. Photo: Galerie Maeght © Calder Foundation New York, Adagp Paris 2014

It was your grandfather who encouraged Matisse, who was very ill at the time, to continue working....

Exactly! And Matisse created his very first paper cut-outs, or gouaches découpés, for us. The only film in which Matisse can be seen working in this technique was made by my father. He was only 20 years old at the time. And we gladly lent it to the Tate Modern. Instead of saying – it belongs to us. No, that's not our way. If the family had been like that, we would never have built such a place for people, for artists. Never.

Fondation Maeght became not only the first modern art foundation in France, but it was also the first art space in the world that was created in cooperation with artists themselves.

It was the first modern art foundation in Europe. And it was also the first building that was created in close cooperation with artists. They discussed with the architect: I want a space like this, I will create a pool in the garden, etc. There had been no precedent. Later, there was the Louisiana, which I like very much. I think it's very similar to the foundation. I maybe don't like the new addition as much, but I very much like the whole aura of Louisiana, the way in which art it exhibited there. Louisiana is not pretentious. The artwork is so wonderful that no added fantasy is needed.

Alberto Giacometti. Le Nez, 1947. AM1992-358 Photo Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Adam Rzepka. © Succession Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris + ADAGP, Paris), 2014

Speaking of the relationship between artists, gallery owners and patrons, it's often assumed that the patron trusts the artist. But your family's story is different – it was the artists who trusted your grandfather. It was actually all a joint project.

Absolutely. And that's exactly the way it's continuing, because I don't know of any other way it could possibly be. We enjoy talking and working with artists. We're travelling the same road, trying to get ahead as quickly as they are. Sometimes it works, other times not right away, but in the end we arrive at the same point. It's wonderful living together with artists, singers, dancers, poets, musicians … to talk and laugh together. It's a pleasure. It's a way to be. But it's possible only because we enjoy being together and moving forward together. My mother very often said, “We have to go on, we have to go on.... If we don't go on, we are going back and we will be in the same place again. That's not our style, staying in one place.” And it's true. We have to go on and to have dreams. Dreams are very important. And ideas. In a way, that can also be said about collecting.

Is not collecting, in a way, an opportunity to live a second, parallel life?

Of course. Sometimes I say, “Oh, how I want this painting, I like it so much!” But it's not possible to get it because it belongs to a museum. But those are dreams. And it's fantastic to have dreams; you wish it, you want it. It's not like you want it as your own, but you wish to touch it, to have it, to turn it. At the foundation it's fantastic to see people moving around a sculpture. I love that. I very often go out into the exhibition hall just to hear what they are saying. The worst is if I hear a child crying in the exhibition hall. Then I rush over to find out what's happened. Most often children cry in a museum because the parents don't allow him to move around freely; they make him stand in one place, and that, of course, is boring for the child. At such times I usually give the child a postcard and tell him to find that work of art in the exhibition. Then, if he finds it, he should come see me in my office....

A child looks at a work of art completely differently because, unlike adults, his senses have not yet been dulled by the contamination of life experience. When standing in front of Munch's legendary The Scream, it is said that young children can actually still hear the scream.

Yes, of course. A year ago a young person wished to meet me. He said he was an architect, and a quite successful one at that. “Great,” I said. “Good for you.” And then he went on and said that he became an architect because the first time he came to Fondation Maeght, when he was 11 years old, it so shocked him in a positive way that architecture became his dream and obsession. That was like candy for me; I was so happy that I threw my arms around him and kissed him. It's very important for me that children feel good at the foundation, because they are the future. The only thing they are not allowed to do here is to touch the works of art. Everything else is allowed – sitting on the floor, drawing, etc.

In a way, your family's story is a testimony to the fact that art can change lives. I'm speaking about the way in which your grandparents overcame the most tragic event of their lives, the death of their son....

I'm always saying that the foundation was born out of a drama. From my uncle who died from leukaemia. Back then the artists told my grandparents to please do something for us; we need a space. New and modern, because we're tired of exhibiting in classical buildings, in all of these hôtels particulier.

The building where we are right now is currently a library. It was originally built for my parents so that they could look out on the Serta-designed foundation building from here. Every day some artist or poet would come in here, until finally the building was no longer called Paula and Adrien's house but the maison d'artistes instead. A few years ago, when my mother died, my father decided to give this building to the foundation, as a memorial. Because it's only natural that life goes on. And for us – their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren – life goes on in the same way. We simply do not know how else to live.

Fondation Maeght

By the way, collecting also means to collect things that have nothing to do with art. There are very many such collections on our family. For example, orange wrapping papers. You've probably noticed that oranges are sometimes wrapped in paper. I'm convinced you've never opened them up completely. Definitely do so next time! They're real works of art. Really! I have a collection of about 3000 such orange wrapping papers and it doesn't cost anything. The design made by the crumpling of the paper is simply unbelievable!

And you can have many such things. If you collect with your heart and with joy, then it doesn't really matter – and it doesn't change anything – whether your objects cost a million, a billion or just one cent. It's a pleasure if you own things that you like. They can just as well be dishes. Many people collect napkins. Why not? One of my father's friends collected buttons. The oldest ones in his collection were from the Middle Ages. He was an old, old man and he collected small buttons. Unbelievable!

There's probably something in the process itself. Maybe collecting is also a way to learn something new?

I think it's because you can find poetry in everything. Some people collect orchids. Why not?

Still, why do you think people are willing to pay unbelievable amounts of money for a work of art?

Why not? If someone wants to live with this work of art and he has enough money to buy it, why not? Some people are obsessed with grand bordeaux wines and no one hears anyone saying, “Wow, he surely paid too much!” It always depends on the situation. If there are two people interested in the same work of art, it's normal that the price goes up.

Nowadays there is much discussion about the relationship between art and the market. But isn't it true that today it's the market that dictates the situation?

Sometimes what happens in the market is very surprising. But, why not? See, if a painting by Rembrandt were to suddenly appear on the market, it would have a crazy price, because there are only a few works by him in this world. In addition, the name means everything. And sometimes even the specific work of art. Take, for example, Jeff Koons. He was just a nothing only a little while ago. Or Basquiat. He lived together with my friend in the same apartment for two months back when he was still completely unknown. And when he moved out, he left behind about 400 drawings. My friend threw them all in the garbage and only saved two or three of them. He said, “I could have been a millionaire today.” I answered, “Yes, but Basquiat was unknown at the time and you didn't like his work. Today everybody is talking about Basquiat – that's great and wonderful, but life also consists of everyday, daily things.”

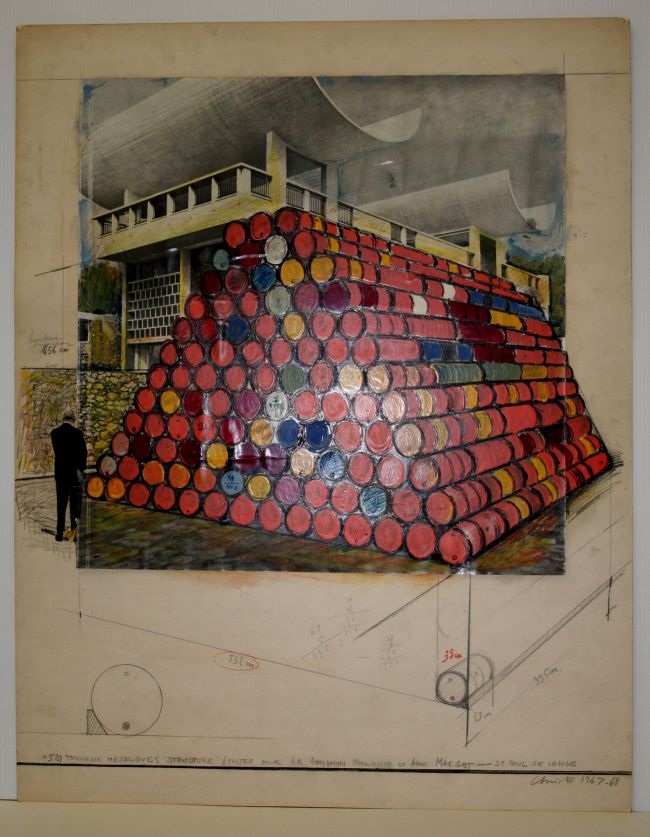

Christo, Projet d’intervention dans la cour de la Fondation: 520 tonneaux métalliques, 1967-1968. Photo: Archives Fondation Maeght. © Christo

The Greek art collector Dakis Joannou, whom I interviewed in Athens not too long ago, bought his first work by the then-unknown Koons in 1985 for 2700 dollars. Currently, he has 30-40 works of art by Koons in his collection, including the famous Balloon Dog, one variation of which was sold at Christie's in 2012 for 58.4 million dollars. Koons and Joannou are now very good friends.

Exactly. When Fondation Maeght organised a Christo exhibition many years ago, he was known, but not very widely. Some people were confused by the exhibition. They said, “Who is this guy and what's he doing?” At the moment, Christo is working on a new exhibition that audiences will soon see at the foundation, and he says he's very happy that his first significant exhibition took place here. And I'm happy, too. Back then, I just met him on the street. It was like, “Hey, Christo!” “Oh, Issa!” There's always room for a new story, no matter whether it's an exhibition or a book. There are so many opportunities to be happy together, and I think collecting is in a way also about how to be happy. For me, as a mother, to be happy about the small rocks my son gave me when he was little. He got married three weeks ago, and I said to him that these small rocks with the small, little drawings on them are my truest treasure. I think every mother considers her child's drawings to be the best masterpieces in the world.

Each day brings some small joy – a rock, a drawing, a work of art, a bird's song. You just have to know how to notice it and accept it.

One of my father's friends was an outstanding photographer who once worked as a reporter for Life magazine. He gave me a photograph of Afghanistan's giant Buddha. When I heard that Islamists had bombed and destroyed it, I cried. I cried because that was a piece of civilisation that was gone forever. That's one of the most terrible things war does.

The same thing is happening in Syria right now.

Many priceless works of Persian art were lost during the Iranian revolution. Where did they go? No one knows whether they were destroyed or taken away and hidden. It's terrible, because they're a part of art history and the history of civilisation that our children will never see. That's also one of the reasons why, if a museum asks to borrow a piece of our artwork for an exhibition, we always say yes.

Georges Braque. L’Atelier VI, 1950-1951. Photo: Claude Germain - Archives Fondation Maeght. © Adagp Paris, 2014

You mentioned Persian art. If we look at Persian rugs, none of them are signed. And it's completely immaterial, because you look at it as a pure piece of artwork. Unlike, for example, contemporary art, in which a well-known artist's signature immediately adds additional value to a work of art.

Yes, that's so. I once met a woman who was in charge of the mosaics section at the Louvre. We talked for a long time, and she cried because she had once found a marvellous floor mosaic in an ancient Roman villa in Iran. She showed me a photograph of it; it was unbelievably beautiful. But she had been forced to cover it with sand, otherwise the Iranian government would have destroyed it. There were nude females depicted in the mosaic, among other things. She knows precisely where the mosaic is located and hopes that one day she'll be able to uncover it again.

Returning to our modern obsession with names and brands.... It's possible that not everything with Picasso's signature on it is a masterpiece, but people are nevertheless willing to pay extraordinary sums of money for just a small drawing.

And why not? Picasso truly was a genius. Just like Braque. I think each artist has his or her place in history. But only time can tell whether now is the time for this artist. That's it.

Fondation Maeght

But, at the same time, there are many very good artists in the world who are still undiscovered and unknown.

Sure. But let's wait. I'm happy that every day a new artist is emerging from a new generation. My son is only 35 years old, still very young. And sometimes he says, “Mother, come, we have to see this new artist's studio.” For me, that's new blood, new pleasure. I've never said to an artist, “That's not good.” I say, “I'm not ready for that.” For the moment. Who knows? In five years, ten years, perhaps I will be ready. But for my son, perhaps it's the right time. My brother will be opening a new gallery in San Francisco in October, and he wants to include classics from our foundation's collection as well as new artists. He's 45 years old, much younger than me. It's very interesting to continue with young artists, with the new generation. And also with new pleasure.