United Arts

Agnese Čivle spoke with Italian art collector Luciano Benetton in Treviso

27/05/2014

Back in the 1960s, the only woolen sweaters that western men knew of were black, brown or navy in color. A daring few may have known of beige. But things changed when in 1965, the Italian Luciano Benetton (1935) introduced the world to the full spectrum of colors. Working together with his brothers and sister, Benetton established the clothing label United Colors of Benetton, which then began to manufacture the classic wool sweater in practically every shade under the sun.

This revolution in fashion wasn't the only surprise up the sleeves of United Colors of Benetton . From scratch, the communication pattern of the company was innovative until when in the late 90s the company began to ruffle the feathers of the public with socially-themed advertising campaigns.

Benetton threw a spotlight on such socially sensitive issues as AIDS, discrimination, political unrest, hate... For instance, recently, the 2011 UNHATE advertising campaign – which featured influential heads of state engaged in kissing one another – elicited a reaction from the Vatican to the White House. In the controversial photo campaign, another sort of reality was being shown: Pope Benedict XVI kissing Ahmed et Tajeb, the Sunni Imam of Cairo's Al Azhara mosque; French president Nicolas Sarkozy kissing German chancellor Angela Merkel; and the presidents of the USA and China – Barack Obama and Hu Jintao, respectively – doing the same.

Currently the United Colors of Benetton chain of 5,000 shops is present in 120 countries. Recently, the Forbes magazine made a list where United Colors of Benetton is among the 100 best known companies in the world.

Although Luciano Benetton has always collected art, especially avangardes, he has started a big project named Imago Mundi, when he retired as President of the Benetton Group, bought a yacht, and set out on a world tour.

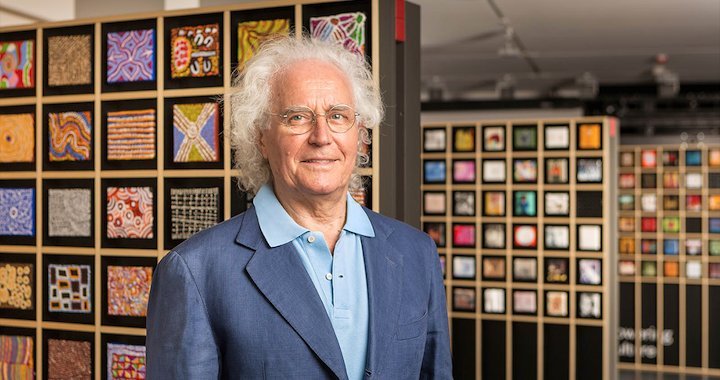

Luciano Benetton. Publicity photo

We couldn't have hoped for a better time to request an interview with Mr. Benetton, since his traveling contemporary art collection, Imago Mundi, is rolling. Our conversation took place in the Italian city of Treviso, Mr. Benetton’s hometown. For over 50 years now, the city has served as both the headquarters for the world-famous business and its manufacturing hub. Benetton is such an intrinsic part of the city that if you ask anyone what key words do they associate with Treviso, most will name three: prosecco, tiramisù and Benetton. This inland city in Italy's Veneto region really is the birthplace of the sparkling wine and the coffee-infused dessert, both of which play a large role in the region's agricultural and cultural profiles – but since the mid-sixties, the phenomenon that is United Colors of Benetton has become just as influential in terms of the region's economics and culture.

The Benetton label is a patron of not only of Treviso's most successful sports teams – Benetton Rugby Treviso – but also of numerous cultural events and projects dealing with the restoration of historic architectural sites.

Architecture, as a part of the Luciano Benetton brand identity, is a separate story in itself. Nowadays practically every world-class fashion house has a special relationship with a “starchitect” – Prada and Rem Kolhass, Chanel and Zaha Hadid, Armani and Massimiliano & Doriana Fuksas, and so on. For United Colors of Benetton, however, this is old hat – in 1964, Luciano Benetton approached the Italian architect Tobia Scarpa, who hadn't yet achieved his “star” status back then. With the construction of the Scarpa’s first factory for Benetton that same year, Treviso became one of Europe's high-capacity industrial cities. The Treviso countryside was transformed into an industrial microcosm in the shape of the Benetton Knitwear Factory, Ponzano (1964) – its 4000 m2 consisting of several buildings with angular roofs arranged around an inner courtyard. Later, in 1980, the landscape of Treviso saw the skillful addition of the Benetton Logistics Centre, Castrette – a “hyperkinetic robot” of ultra-modern machinery on raised pillars, all covered by a roof with twenty vaults. 1995 saw the completion of the Benetton Plant, Jeans and Tailored Clothing Division, Castrette – an 190,000 m2 factory for the production of sewn clothing. Suspended with cables from titanium towers that rise above the roof of the structure, the building's architectural image is almost metaphysical in nature.

Working in tandem with architect Scarpa, Luciano Benetton has also revived several historical and WWII-damaged buildings in and around Treviso, including the 17th-century Villa Minelli in Ponzano; the 18th-century palladian palazzo, Villa Loredan, in Venegazzu; the 19th-century Relais Monaco in Ponzano; and the Hotel Monaco on Venice's Grand Canal.

Another substantial renovation project is currently underway in Treviso – over the next two years, the restoration and modification of the 11th-century San Theonistus church will be completed, after which it will serve as, among other things, an art space for the Fondazione Benetton Studi Ricerche.

Founded in 1987, the Fondazione Benetton Studi Ricerche is housed in the Palazzo Caotorta and the Palazzo Bomben-Mandruzzato, two private homes from the 14th- and 15th-centuries that were typical of the Veneto region. Closely following historical descriptions, Tobia Scarpa rebuilt the mansions almost from anew in 2003; features include wall drawings, Venetian stucco plastering, 16th-century ornamentation that was discovered in the ceiling panels, and reconstructed Venetian marble flooring of the type found in the architecture of medieval Venice.

The main activities that take place within the canal-side, white-walled facade of Fondazione Benetton Studi Ricerche are landscape management and the research of outstanding places to be preserved. Locations researched range from the nearby surroundings to the bush forests, mangrove swamps and Atlantic rain forest of Brazil's Barra de Guaratiba ecological reserve. One of the Foundation's projects is the International Carlo Scarpa Prize for Gardens, established in 1990 and awarded annually. In evaluating landscapes throughout the world, the scientific panel of judges look at such characteristics as the synergy between the site's history and its natural state, and the site's balance between preservation and innovation; the award is presented to the institutions or persons responsible for the maintenance of the relevant landscape. In 2013, the prize was awarded to Skrúður, a modestly-sized fruit and vegetable garden in northwestern Iceland, sited on the edge of a fjord and just a few kilometers south of the Arctic Circle. If a picture of the surrounding landscape were made into a jigsaw puzzle, the garden in question would fit into one single piece of it. Nevertheless, this garden project that came to life at the beginning of the 20th century was both ambitious and sustainable – created as an experimental garden not far from the village of Núpur, its purpose was to prove that seeming obstacles such as harsh conditions and unsuitable soil could be overcome to produce a fruitful and bountiful garden.

The Foundation also has a library, an archive, and a very rare and special collection of ancient maps on landscape and the territory at large. Students have access to more than 60,000 books, 200 periodicals, 10,000 maps and 30,000 photographs that deal with landscape planning and management.

This is also the place where Benetton's cultural project – the Imago Mundi contemporary art collection – is currently being curated. Imago Mundi consists today of more than 25 collections of small-format artworks (10 x 12 cm) sourced from 30 countries. The project was first opened to public viewing as a satellite exhibition of the 55th Venice Art Biennale; almost two thousand works from Australia, India, Japan, South Korea and the USA were put on exhibit.

The Imago Mundi project organizes traveling exhibitions, publishes regional art catalogs, and upholds the Internet platform www.imagomundiart.com. Luciano Benetton's stated objective is to remind us that ideas, meanings and inspiration are not monopolized products – they have been borne of interaction and communication between West and East, North and South, and through the converging of the world's cultural experiences.

The collection has been assembled according to the voluntary principle – none of the works have been obtained through purchase. As Luciano Benetton himself surmises, this could be the reason that most collectors – his peers – do not fully comprehend this project. In spite of this, Benetton continues down the path he has started, and the compilation of a collection – one that began with him carrying home in his own suitcases these artistic “business cards” acquired during his travels – has now been entrusted to a group of professionals scattered throughout the globe.

Luciano Benetton's inspiration for this collection was based on the principle used by the Swedish botanist, Carl Linnaeus, to classify organisms, and which is now the universally accepted method of naming plants. In the case of Imago Mundi, the collection is being created as a world art map, or global art catalog that is constantly evolving and developing indefinitely into the future. By the close of 2014, 140 works by Inuit artists are planned to have been added.

The increasingly global Imago Mundi project is further evolving and will involve 80 countries by the end of next year for a total of over 10,000 artworks.

Also, among other exhibitions, this year, in cooperation with the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, an exhibition will open in Rome in autumn featuring 15 African collections.

Since the collection's format and mobile capacity requires special storage and exhibiting solutions, the Imago Mundi exhibition set-up, created by Tobia Scarpa, is based upon that of a collapsible chess board. When opened up, it is reminiscent of a colorful and bountiful box of candies. Every “box” features a different part of the world: “Ojo Latino” contains 200 “candies”, or artworks, from Venezuela to Argentina; “Flowering Cultures” – 205 works from India, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka; “Looking Eastward” – 162 miniature artworks from Russia; and “Painting the Dreaming” – 216 works by Aboriginal Australians...

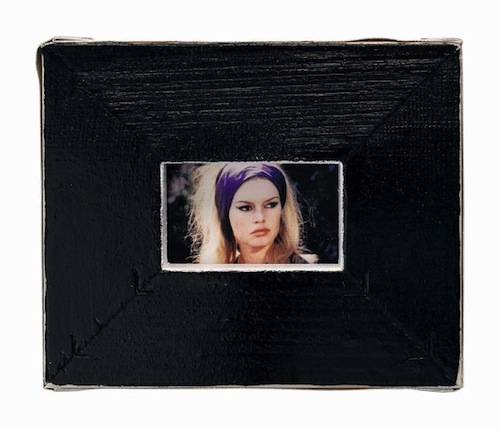

Imago Mundi - United States collection: Steven Soderbergh. Bardot No. 1. 2013

Every piece of “candy” has been made by a different artist – each one with his or her own identity, technique and captured concept. In the Aborigine collection, for instance, there's a work by the artist Tommy Watson; the first time Tommy ever saw a white person, he was already 60 years old. Other works have been created by artists that are quite distanced from painting, such as in the USA collection the American film director, Steven Soderbergh; the Scottish musician, David Byrne; the Japanese musician and actor, Ryuichi Sakamoto; or architects Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry in the Vienna collection.

Every artwork is like a personal business card – a small key to the large world of their art. The small format serves as a distillation of the artist's soul and essence into ten by twelve square centimeters; of course, this has not been an easy assignment to fulfill, and often times the artists have cleverly used the backside of the space, or gone over the edges – much like during the very last seconds of an exam, when the student tries to squeeze-in whatever last pieces of information he can remember onto the remaining page margins.

One of the peculiarities of the Imago Mundi project is to capture all cultures, to date Imago Mundi has created a rare art collection of pieces by Aboriginal Australians – the indigenous people of the Australian continent that make up only 2% of the current population. Since the 1970s, which is when the Aborigines first transferred their art from the sand to the canvas, the Australian outback has become a territory for contemporary art in which the cartographic style of the Aborigines has become more abstract, minimalistic and geometric, yet it is still imbued with a pulsating density of energy and rich symbolism. Aboriginal art began its foray into the contemporary art world at the beginning of the 90s – first with its inaugural participation in the Venice Art Biennale in 1990, and then with a victorious presence at Art Cologne in 1993.

Imago Mundi's Aboriginal art collection has been curated by John Ioannou, who reveals that he spent several months travelling 16,000 kilometers of the Australian outback. In preparation, he selflessly studied the Aboriginal culture, traditions and languages, thereby gaining the trust of the tribes. After a three-week-long initiation ceremony, the tribal members gave him greater access and he could continue on with his main priority – introducing the mystery of this wonderful art to the world at large, and helping the Aboriginal artists develop this renaissance of their art by pouring in new blood into one of the world's oldest cultures.

Large-format works by Aboriginal artists can be found in Luciano Benetton's contemporary art collection located in the basement level of the Castrette clothing factory. Tobia Scarpa has created a special mechanism, based on a conveyor belt, with which to exhibit these large-format pieces of Benetton's collection.

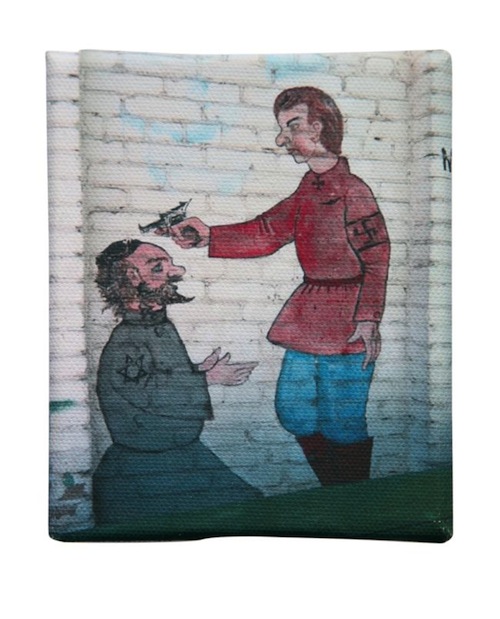

Imago Mundi - Russia and other Eastern European countries collection: Bella Boyeva. Untitled. 2010

When you began work on your first clothing collection in the 60s, what was your relationship to art at the time? What role did art play in your business?

I have always been interested in art but I cannot claim to have begun collecting immediately. My work absorbed my time completely. However, it is thanks to my work that I came into contact with the cultures of the various countries I developed business dealings with; my passion for travelling grew hand in hand with the growth of my business.

I have always been fascinated by different races and their cultural and artistic expressions.

My project Imago Mundi in fact originated from the background of knowledge accumulated over the years.

My quests for Imago Mundi have not been linked to the monetary worth of the artworks, but rather to giving visibility to the largest possible number of artists, praising their native cultures through exhibitions, catalogues and the Imago Mundi website.

But to go back and answer your question, I'd have to say that since the very beginning when I started to make clothing, I have been interested in finding new ways of matching colours that apparently might be clashing and this is why I was greatly inspired by two masters such as Kandinsky and Klee whose work on colours and light guided me in creating my collections.

I went to exhibitions, acquired their art catalogs . I observed how the artists combined colors. The public liked colors in the collections.

How would you comment on the cooperative projects going on between fashion houses and the contemporary art world?

There is often a close relationship between fashion and art.

Art describes what is going on in society, where it is heading – and this is what those working in fashion must try to understand and interpret.

.jpg)

Imago Mundi - Senegal Collection: Yankhoba Fall (YA). Clamping and Blocking System. 2013

Looking back from the perspective of today, do you believe that the once-scandalous United Colors of Benetton advertising campaigns now have an artistic value?

Yes, definitely.

What's the current situation with the politics concerning the label's advertising campaign?

The times are changing – the company is now going into the hands of managers; it is no longer just the Benetton Family's business.

They will have to create new strategies that will be, of course, different, but they will be in sync with the history of the corporate label.

Back then was an unrepeatable experience, we loved it ; that was the way to work without getting tired.

The campaigns touched upon social issues of the time and this created strong and controversial debates.

Imago Mundi - Senegal Collection: Aminata Diobé Taye. Untitled. 2013

What is your opinion on the role of business in art? Or in other words, what do you think of today's art market?

Today other forms of more speculative investment have moved in alongside the traditional collectors, such as investment funds and banks active in the art market.

Additionally, the number of countries undergoing rapid economic growth is increasing. The new wealthy want to enter the art market and they are ready to pay increasing sums to get in – even if it's only to use the art as a symbol of their status.

But actually, I think that what is going on today is not much different than what happened during the Renaissance era.

During this period of cultural advancement, it was the Church and the monarchies, who built grand palaces for themselves and filled them with art in order to gain prestige. The simple folk were even forced to go to these temples of grandeur and then expected to gape in wonder and compliment the owners.

The same is going on right now with the exhibitions of notable artists. Big exhibitions are organized, and people feel compelled to go see them – they want to be there and see it, so that afterwards they can have a sense of belonging to a certain group.

The only difference is that today the price of a piece of art is dictated by the gallerist, or art dealer, a profession created during the last century, whereas during the Renaissance, the contract was directly between the artist and the buyer.

Nowadays it's like a game that is continually evolving and becoming ever more important.

On the other hand, the art dealer is a good presence because he helps to financially support the artist, which then allows the artist to have a better life and to be relaxed – so that he can work and not have to think about how to satisfy his elemental needs.

.jpg)

Imago Mundi - Senegal Collection: Amadou Lamine Ngom (Docta). There Is Only God. 2013

If we tread nearer to the subject of the Imago Mundi collection, but don't yet completely leave the subject of the art market, is it possible that in the future, this project – with its “global art catalog” format – could become a real platform for buyers of art?

Given that the 10x12cm Imago Mundi collections, due to the nature of the project, will never be the object of commercial negotiations, I would like to believe they will be useful through the way they introduce little-known art and artists to people who are active in the art market, as well as to people who are simply interested in art.

Exhibitions, catalogs and other activities will ensure that the artists will be noticed in various places all over the world, however, from here to saying that the project will become a stable reference point for the contemporary art scene is a big leap. Nevertheless, it could become a launch pad for numerous artists, that I do believe.

The Imago Mundi project is mapping 21st-century contemporary art by indicating what is available in each particular art environment. If this goal is met, I will be satisfied. Africa immediately comes to mind – a very large and unimaginably interesting continent. We have decided to study the continent from north to south, discovering countries that have yet to be discovered in terms of the global art market.

I believe that this project could become a new format for telling the story of contemporary art history.

Then that would be the work of two involved parties, for in this project we're working together with specialists – curators, museum directors and art historians. It's up to them, mostly, to tell us what is going on in the world of art. Hand in hand, we discover what contemporary art has to offer.

Imago Mundi - United States collection: Jacob Hashimoto. Untitled. 2013

Do you completely rely on the specialists' choices?

We try to have the necessary guarantees regarding the experience and competence of the various experts we involve, and yes, I trust them. We use several experts for each region and their task is to try to provide a picture of the established and emerging artists in the territory they represent.

Even though currently there are more than 5,000 items in the collection, can you think of some very special or unusual pieces that you would like to highlight?

There are many like that. For instance, in the Chinese art collection there's an artist who works with the aid of a magnifying glass because he uses just one single hair as a paintbrush. This piece really makes one think about what it is that we are looking at, and how it has come to be. The Japanese artists have become quite carried away with embellishing the back of the small-format pieces, so that the backs of their works are no less special than what's on the front.

Some works have been created by artists who come from disciplines that have little connection to painting – musicians, photographers and architects. This aspect makes the collection even more interesting and multifaceted.

Do you tend to form personal relationships with the artists? Is that important when selecting a piece?

Yes, I have occasionally visited artists in their homes, and I greatly value this sort of opportunity. But this is not a determining factor in the selection of a work; anyway, I don't get to meet them that often. To meet them all – that would take years.

Have you personally met any of the Australian Aborigine artists?

I haven't. It's hard to visit them – they live far from civilization, in their own territories in the desert. It's not that easy. The curator working with this part of the collection has been “initiated”, he is one of the very few white people to have been welcomed within a community and who can participate in their rituals. John is fluent in their languages which is a fundamental prerequisite to deal with the Aboriginal tribal community. His job isn't easy – the creation of the collection took over a year and there was more than one unusual occurrence with which he had to deal. Sometimes, after having come to an agreement with the artists about the making of a work, he would return to the same place after a couple of months, as agreed, but either the people weren't there anymore, or in the best case – they had forgotten about their promise to make a work for him... At other times, it was hard to convince them of the small format – that was something that they just couldn't comprehend, nor wanted to accept.

I think things may go similarly with the Inuit collection.

It was your world travels that inspired you to initiate the Imago Mundi project. What does traveling mean to you?

I traveled for years because when I was heading the business, that was my job. But I always set aside time during these business trips to see something more, to discover something new. This ability to travel has always made me feel very happy, emotionally fulfilled and has allowed for my growth.

Imago Mundi - Russia and other Eastern European countries collection: Oleg Kulik. Kindergarten. 2011

You also took a trip around the world by boat. How did you come up with this idea?

While traveling for business, I always saw the big cities, I stayed in hotels and I met with business partners – that was a part of my life. Actually, that was my life while I was working. But I wanted to go through a different experience – see the world from a different vantage point and as a grown-up, experienced person.

Boating – now, that's a really special way to travel. When you travel along the coastline, you have to set anchor in the harbors, which are usually in the center of the cities. I remember how we ended our 2013 trip in the harbor of St. Petersburg, when we set anchor right in front of the Hermitage – we disembarked from the boat and went straight into the museum.

The more you traveled, the more you got to experience art, and most likely, you increasingly got to know it and understand it...

That's still happening. When I visited Latvia last summer, I acquired some large-format artworks that were done with an interesting technique [in August of 2013, the Luciano Benetton contemporary art collection acquired five plasticized paintings by Kristaps Ģelzis (1962), from Ģelzis' solo show, “2013”, held at the Māksla XO gallery – A.Č.]

There is still much to discover in the Baltic States. Some great art is being created there.

It is known that you've begun working with the Riga gallery, Bastejs. Can you tell us anything more about that?

We visited four or five really great galleries in Riga. Together with the panel of experts from the Baltic region, we encouraged the head of the Bastejs gallery [Baiba Morkāne] to take part in the Imago Mundi project to create a snapshot of the current contemporary art situation there. We estimate that the Latvian catalog should be ready by October of this year.

Imago Mundi - United States Collection: Ryuichi Sakamoto. Stain. 2013

Can you describe what if feels like when you add a new piece to your collection? In this case, I'm referring more to the addition of large-format works.

As a collector, I fall more on the side of concentration rather than emotion. I visit a lot of exhibitions, and I'm very interested in what I see.

I'm not looking for big names, I'm not chasing after investments, but what I greatly value and what really moves me and gives me energy is discovering new talent.

I also give preference to emerging artists. I acknowledge their ability to experiment, their readiness to announce themselves to the world, and their willingness to compare their strengths with others. Of course, one can never tell beforehand who among the currently emerging artists will truly become the big names of tomorrow.

What advice would you give to people just starting to collect?

My advice, if I can give it, would be to be careful in choosing dealers or galleries. A smart specialist is someone who can bridge the communication between the collector and the artist by following his developmental progress, because new talents take time. Compared to an artist, an art dealer has specialized in communication with people, he has access to a wide circle of contacts, and he states his opinions.

***

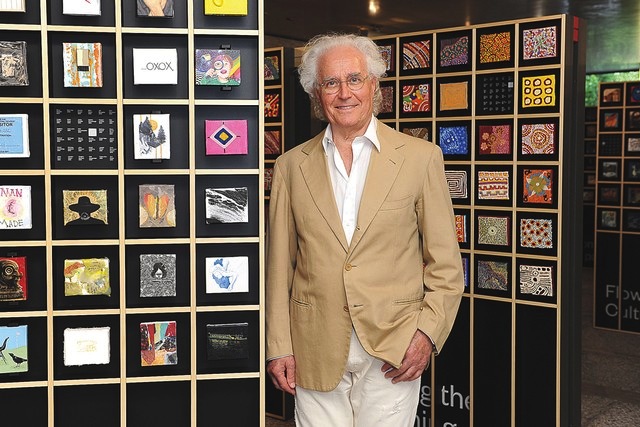

Luciano Benetton next to Imago Mundi. Publicity photo

On the table in front of me there are piles of both opened and not-yet-opened art catalogs. When our conversation had steered onto the subject of the Imago Mundi project, with almost every new sentence Luciano Benetton got up and went to his shelf of art catalogs to show me what he was talking about. While I was glued to one catalog, I didn't have time to leaf through all of the following catalogs that eventually began to pile up... Mr. Benetton is definitely one of those people whose enthusiasm and zeal easily rubs off on others. If there's something that he likes, even the most skeptical person will, over time, come to accept it as well.

In addition to his power of suggestion, Mr. Benetton is in possession of something else just as hypnotic – that indescribable collection of traits that one calls charisma; in his case, the charisma is accompanied by a charm that is warm and disarming. An open face, aqua-marine eyes and silver hair, along with the iconic orange sweater and Italian hospitality...

Through the open window of the Fondazione Benetton Studi Ricerche, we hear the ringing church bells of Treviso. Our conversation comes to an end, and Mr. Benetton invites me for lunch outside of the city together with his team. Afterwards, he leaves us in the capable hands of his assistants and we are shown the inventive Imago Mundi exhibition stands, as well as the Benetton large-format collection, which is stored in its own special facility in the Castrette factory.