Diagnosis: Collector

An interview with Pierre-Christian Brochet

Elizaveta Borovikova

27/05/2013

Collectioner and publisher Pierre-Christian Brochet is one of the few private collectors of contemporary art in Russia. He moved here from Europe already twenty-two years ago and during this time has managed to accumulate a collection that is virtually a complete record of Russian art of the 1990s and beyond. He explained to Arterritory.com how people catch the bug of collecting, how he manages to satisfy his craving and which artists help him with this.

What does collecting mean to you and why are you doing it?

I simply collect what I like. I love Russian art, since I live in Russia. If I lived in Brazil, I would definitely be collecting Brazilian art and in China I would be collecting Chinese art and I would not give a damn about Russian art. You live only once, in the country that you chose depending on the goals you have in life. At some point, I decided to live in Russia – perhaps not forever, but I have been here already twenty-two years. And as soon as I came here I understood one thing: the only part of the society that holds an interest for me is artists. So I immediately entered that milieu both in Moscow and in St Petersburg. Two or three months after I first came here in 1989, I already was familiar with Zvezdochetov, Mironenko “Champions of the World” and others. Six months later in St Petersburg I met Bugaev, Monro, Timur Novikov. At that time, these were the only people I could relate to emotionally. They were people whom I needed in order to feel good in this country. You got the feeling that it is they who are changing the course the country follows. I decided that it was better to live with such people instead of those who only watch television. Today the situation has changed. I don’t think that the young artists are having a serious impact on the political life of the country, but they have some influence nevertheless. And that’s good.

Dubosarsky & Vinogradov. Bears. 150 х 200 cm. Oil on canvas. 2008

My ancestors were rather poor people for whom the concept of heritage was however very important. The concept of heritage means that at some point you begin to understand that you are not the first person on earth, that the traditions that you favor and value in behavior, religion and civilization were created before you came along. The things that I love seem bourgeois enough, yet in reality they signify not so much the bourgeois as the civilized, the concepts that we believe in, like religion, tolerance etc. All these values we can support if we understand the importance of heritage. And once you understand that heritage represents not only what your ancestors were doing but what was accomplished by civilization at large, by the entire society that lived before you appeared, you understand that if you believe in this civilization, it is your duty to move it along in some way. There is not just one way of doing this, there are several. One of them is to support the art of young artists, which is what I do. And it’s not even important if I have children, that’s not the point. I am not assembling my collection in order to leave it to them; I am assembling it so that my great-great-grandchildren would remember that they had a really cool great-great-grandfather who did not live his life in vain, who helped civilization along – the civilization he was born into, and it continued because he did what he did.

I love to live and communicate with people, with artists, because that’s where life is really found. You have to be certain that you have created an inheritance and prepare it for the future.

Culture and development of art in the final analysis consist of very tense, incomprehensible relationship between lunatics who happen to be artists and lunatics who happen to be patrons of artists and collectors. These two groups are sick. Yet artists are keenly aware that they really look at the world with different eyes and have the right to show us this world the way they see it. Collectors and patrons are also ill, but each collector has his own illness. Some want to have it all. It is a Freudian understanding of phallus, the desire to possess the whole organism. We understand that it is impossible, yet there is this striving. There are these other collectors who are enraptured by the madness of the artist that they are deprived off, so they obtain the works of these crazy beings, for the process of their creation is not available to them. I am not an artist, I have never picked up a pencil – it’s just not my thing. I understand that it is simply madness and it is possessed by a certain category of people that I find really exciting. There are people who understand that historically art is connected to opulence and creation of collections: basically it is the prerogative of kings. They think that in order to become king it is necessary to collect. Such were the ambitions of the Medici at the beginning of the 16th century, such were the ambitions of Lodovico Moro in Milan at the time of Leonardo. Some of these people were bankers, others generals. Each person has his own ambitions that can be fulfilled through art. And you cannot get a cure from collecting. It is an untreatable disease. God forbid that you should become a collector.

What are your guiding principles in purchasing works of art and what are your latest acquisitions?

In making my choice I don’t follow a particular principle. The only rule is that the work of art has to represent something very important for me in the historical or political sense, it must be related to the history of art or with some sort of reminiscences.

Olga Chernysheva. Luk (at this). 98 х 137 cm. Photograph. 1997

Over the past two or three years I have been collecting only young artists, with the exception of two or three authors whom I already have in my collection. For instance, I recently acquired a very important work by Dubosarsky-Vinogradov, which features small wolves and a child in grass. But essentially I collect young artists, either those who have participated in the “START” project or those whom I have met through other channels.

I travel a lot and that gives me the opportunity to see what you can’t always observe in Moscow. For example, in the building of “Izvestiya” there was a fair parallel to Art-Moscow and there I encountered two artists from Voronezh, Ivan Gorshkov and Kirill Alekseyev. Right there and then I bought five or six objects from Kirill and said to Gorshkov that as soon as he creates something new I would like to take a look. So he invited me to an exhibition at “START” where there were these wonderful sculptures of his and I bought one sculpture from him, then another two, then three paintings and twenty drawings. It’s the Voronezh gang, the school started by Zhilyaev. The guys were here but I went to Voronezh to choose the best works there.

I bought two works from a girl from Kemerovo who studied in St Petersburg – Tatyana Akhmetgalieva. Then at some exhibition I saw works by Andrei Kuz’kin who is represented by the gallery “Otkritiye” and I acquired two small sculptures and a canvas from him. I also have two metal boxes from Kuz’kin – he used to packed his things in them. I think that it is one of the most important works of the last decade in Russia. Its relationship to heritage to me is a very important aspect. I acquired quite a lot of Chtak, but that was a long time ago – the first works I bought in 2006 or 2007. Then in the Paperworks gallery I bought his wonderful painting that was in the Moscow biennial catalogue last year. When I was in Italy, I suddenly realized that he had an exhibition, I think in 2009, and he practically did not sell anything. Then I bought the entire exhibition on the spot, in Italy.

In “START”, I bought the works of Yakovleva and Anya Zhelud’: both paintings and things of metal and cement – flowerpots, ten pieces at least. I also love Yulya Ksul’nikova from St Petersburg: I have three big canvases of hers. In Perm I saw wonderful works by two girls who made “non-falling bombs” and immediately bought three such bombs.

What is your attitude to contemporary technologies in art? Do you collect works made in the new techniques?

I have a few videos, also by young artists. The first video that I bought was I think from the “Blue Noses” where naked girls are lying on a billiard table. I also have a video by Monro and a wonderful video by Buldakov called “Crash Test” in three parts.

But I really love painting and not only because it’s bourgeois. Despite these many assertions that painting is dead, I think it’s nonsense. Be it as it may, there is a certain category of artists for whom painting is their language, we simply have to acknowledge this.

Valery Koshlyakov. Landscape with River. 300 х 360 cm. Asphalt, foil, acrylic on canvas. 2006

And what do you think of conceptual art?

In my opinion, a conceptual artist is a phenomenon that can appear only where philosophy does not exist. In countries where there are powerful philosophers, like France, there is no conceptualism. No artist can express through his art more than a philosopher expresses through the written word. Conceptualism exists in Russia and America where, for various reasons, there is no philosophy. In Russia, there was no philosophy in the Soviet period and there is none even now, but there are philosophers who understood that the only available form through which their opinion can reach the society is art. That’s why they became artists. But I am not sure that it is really art. Because of this I have very few things that are directly connected to conceptualism. By education, I am a philosopher and have great difficulty dealing with works that finally can only serve as illustrations to philosophical texts. That’s the case with Koshut, for instance. We had a really hard conversation a long time ago, it’s been twenty-eight years. Then I told him that his latest work is just an illustration to a text by Derrida criticizing Freud. And he got very excited because it was true, it really was just a nice decoration to the views of Derrida in the form of pictures with neon. It’s not always the case with conceptual artists: some works by Monastyrsky are an exception. Yet such a phenomenon exists.

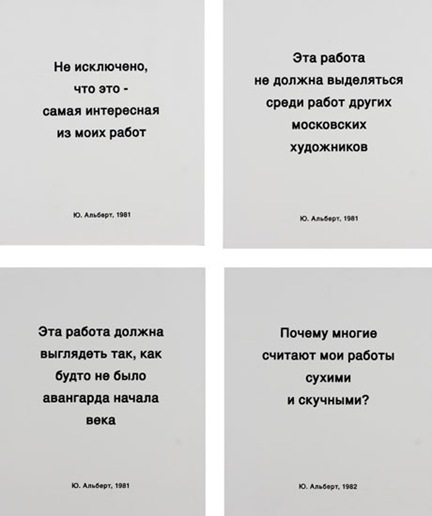

Yuri Albert. From the series Work with Old Texts 1981–1982. 60 х 50 cm, 4 parts. Stencil and acrylic on canvas. 2007

I don’t think that every artist qualifies as a philosopher. We have to remember that art exists also, say, in a gesture. And a gesture is not necessarily an idea. My wife definitely possesses an energy of the gesture that leaves a strong impression and provokes emotions. And I think that the goal of art also consists in this: not to shock but simply to convey emotions that give you the opportunity to think further. That does not mean that in these works an idea as such is present. Emotions appear when a little bridge appears between two ideas, and art allows us to build such bridges. When you look at the photographs of Olga Chernysheva, at these hats of old grannies, one can begin philosophizing that these are conceptual works, that it’s social art. But to me these works are very dear because I never paid attention to these hats and started looking at them only after seeing Chernysheva’s work. And the emotions that I get every winter when I see these hats or ones like them, to which I pay attention only because of an artist who has opened for me new emotional possibilities – that’s wonderful. I walk out on the street in winter and I see a green “cactus” or “mushroom” and this emotion is there because of art. But I have no idea if Chernysheva had an idea. Perhaps she was just taking pictures of hats.

Olga Chernysheva. Waiting for a Miracle. 80 х 125 х 10 cm. Light-box. 2000

Why do you think there are so few collectors of contemporary art in Russia?

In the course of seventy years, they unfortunately tried to build a country that was never really built. There was an idea which was never carried out, I mean, socialism. In the course of seventy years, the country lived with a destroyed past, with a destroyed sense of heritage and since there was no revolution at the end of this period and there was no analysis of what happened, today no one is at peace regarding their past. No one can claim with certainty that in their family no one had NKVD connections, that no one had anything to do with the destruction of that culture, that heritage. All churches, all altars, all country estates, all family ties were destroyed. It was all destroyed in order to create a new man who never really appeared. I think that the main problem in today’s Russia is exactly the fact that the concept of heritage has not been formulated because it is impossible to strictly formulate who our predecessors were. And so it is very complicated to do what collectors of contemporary art do, i.e. to build a future. When in 1981 I lived in West Berlin, all the leftist young people had one problem, which in Germany was solved but was never solved in Russia. The issue was solved there like this: they understand that their predecessors for some time supported Hitler, supported all that system. Yet the task at hand is not to condemn them but not to allow a similar situation to develop again, should there suddenly appear an ambitious politician who would like to push the country in a similar direction. In Russia nobody asked this question and that’s why nobody is collecting contemporary art.

The culture of any country is created by a very narrow circle of people – it can be the aristocrats, it can be the bourgeois. The Russia which is now the pride of Russians is what was basically built by ten families which had a very clear understanding of heritage.

Anatoly Osmolovsky. Bread. 50 х 40 cm. Wood. 2007

Can institutions replace private collectors?

I suspect that if art develops not because of collectors’ efforts but on account of curators’ ambitions, at some point a problem appears. Collecting is like psychoanalysis. When you have a problem, you go to an analyst and you pay him rather big money, you lie on the couch, you tell him. But the fact that you are paying is for Lacan very important. It’s the same with art. You go to crazy guys, to artists and in some way get close to their works by acquiring them. And you feel much better. Whereas if you are a curator, you are not spending your own money. Nevertheless, you possess a lot of power. And you have to prove that you have a better understanding of the world and today’s art than other curators who are total imbeciles and don’t understand a thing. And I wouldn’t be surprised that this kind of a struggle may transform into a situation where artists are being observed and they have to create their works and participate in projects in a direction dictated solely by the ambitions of a curator. It is dangerous enough. You pay and you receive. Whereas if you receive and don’t pay, I am not sure that the system is really functioning. I am beginning not to believe in all these pseudo-critics and pseudo-curators who put together exhibitions just to satisfy their desire for power and push artists into directions that are not genuine for them. Already after the Second World War, contemporary art was being collected throughout the world, in all museums. All this gradually evolved to the point where Jean-Hubert Martin put together an exhibition titled “Les Magiciens de la terre” at Centre Pompidou in 1989. At this exhibition, Martin presented himself as the main demiurge of the world: he was no longer a curator but a super-artist. But he doesn’t have an easel with paints, he has just a huge number of other artists, creators, and he chooses among them and creates an exhibition, which in and of itself is an art object, a whole installation. And who is he now: a curator or a new artist on a new scale who uses works of other artists instead of paints?

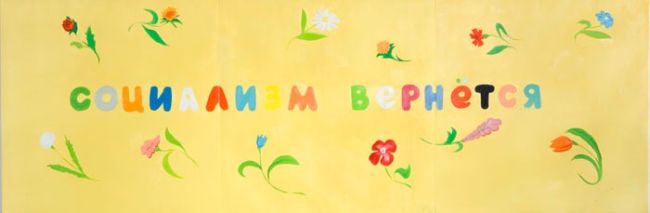

Pavel Peppershtein. Socialism Will Return! 141 х 423 cm. Acrylic on canvas. 2006

I don’t ever order anything. I am observing what artists are doing and choosing from what already exists what at a particular moment and in a particular context seems to me most characteristic. And I pay money – no matter, a lot or little. And I can always explain why I bought this or that thing. The organism of my collection exists, it develops, something goes away, something changes. Yet it fully conforms to my concept of life and the world as well as my concept of creating heritage for the future. I am not sure if curators feel this responsibility. A curator receives a salary and does his work in the name of struggle for power, to become the coolest curator there is. And in this context, curators allow themselves things of whose virtue I am not sure.