Do works on paper absorb the economic storm?

Ekaterina Drobinina

18/02/2016

“Think of me as a person who first brought a Rolex watch to Russia – there were times when this luxurious watch was not sold here, but today you can easily buy one in Moscow”, Egor Altman tells me as we meet in his gallery a couple of weeks before the New Year.

The Altman's gallery sells prints by Marc Chagall, Salvador Dali, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Takashi Murakami. It was opened in November 2015, which was probably not the best timing, I assumed, given the economic crisis the Russian economy was falling into. “Crisis is a time of opportunities”, argues Mr. Altman.

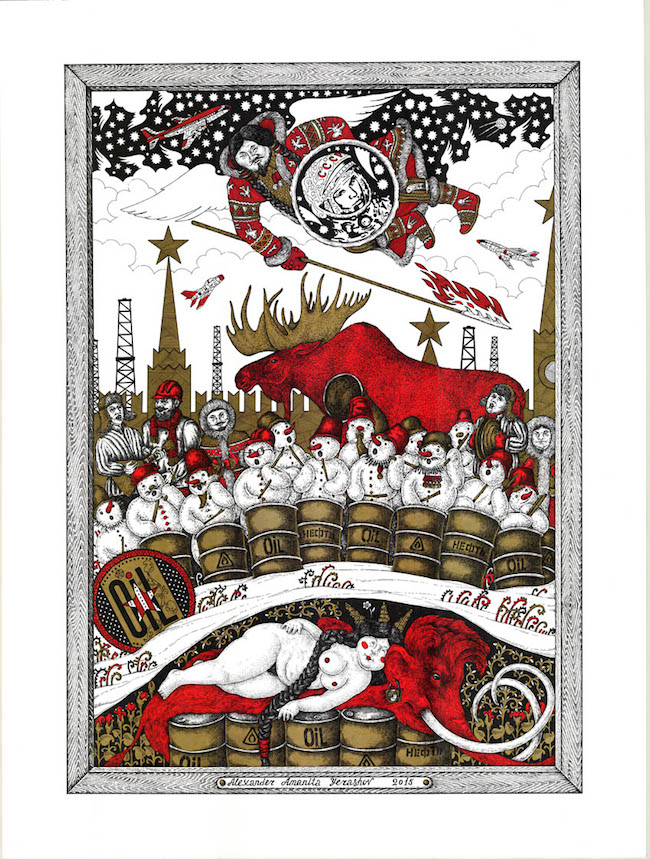

Amanita from “Oil” series. Courtesy of Roza Azora gallery

In the end of 2014, when the Russian economy was falling off the cliff, and the national currency was losing its value so fast that some retailers did not have time to change the price tags, many art-experts forecasted that the only segment of the art-market that would do well in these hard times was works on paper. Sketches, watercolours and prints attract people with lower incomes compared to those who buy at the evening auctions of Christie’s or Sotheby’s.

“There are few people who can afford a Rubens on canvas. Even if you try to get a mortgage from a bank and spend it on a Rubens instead of a flat, you won't have enough money”, says Alexey Zaitsev, owner of Albion, a gallery that deals in Russian and Western paintings and works on paper. “But a lithography by Rubens is affordable even to the middle class”, he adds.

The middle class in Russia is still a vague notion that economists define in a variety of ways: some would call a member of the middle class a person who earns no less than 60,000 rubles a month (less than $1000 today), while others would expect him to have a flat, a car and a country house. However, unlike Western art-lovers, who frequently attend art fairs featuring affordable works, or purchase pictures online, where prices are lower than in brick-and-mortar galleries, Russian middle-class customers lack the tradition of living with art, agree all art experts.

Katya Rozhkova “Underwood”. Courtesy of Roza Azora gallery

The tradition to collect art was destroyed by the Bolshevik revolution in 1917. In the USSR, having works of art hung at home was considered bourgeois. In the 1990s, the nouveau-riches came to galleries to buy paintings by the Russian artists - Aivazovsky, Shishkin, Savrasov, Polenov - whose works illustrated their school books. The gallery owners call them “the club of 'Rodnaya rech'” (Russian for “My Native Language” – the name of a common primary school textbook in the 1990s).

However, since then the customers have changed. They have become more educated and careful about what they spend their money on. “At some point, people understood that art is not just pictures from your school textbooks. There were times when it happened every day, but now this is rather an exception”, says Alexey Zaytsev. He tells me a story about how in the 90s, a dealer would buy a work of art by an unknown artist for a couple of thousand euro at a local art fair, and then wanted to resell it in his gallery. The work turned out to be a painting by Nicholas Roerich, and was sold for the price of an apartment in Moscow. “Such stories used to take place very often, but they hardly ever happen today”, he says.

Marc Chagall “Meeting of Ruth and Boaz”. Courtesy of Altmans gallery

However, the situation has been changing recently, and more people are willing to buy art without spending millions of dollars. And this trend has been typical not only for the emerging art-market, such as Russia or other former USSR countries. According to some experts, oil paintings were popular among Western consumers in the early 90s. Today they prefer less expensive works of art – those made on paper. A work on paper is always affordable, no matter which period this art comes from.

Katya Rozhkova “A Bucket”. Courtesy of Roza Azora gallery

The market for works on paper has seen a large influx of buyers from China (it has been previously reported by some news sources that the most expensive work on paper – Egon Schiele’s “Lovers- Self-Portrait with Wally” – was sold at a Sotheby’s 2013 auction to an Asian buyer), Russia, India and other emerging economies in the 2000s.

But for many of these neophyte art-customers, the most important thing is to own a work by a famous artist.

“For a Russian person, it is important to buy a brand – no matter if it is a car, a bag or a work of art – because a person wants to identify himself with success and luxury. In Russia, people think that owning a work of art at home proves you are wealthy, but this work of art must be known and recognised by everyone. Russian artists are not so recognisable”, says Egor Altman without a hint of a smile. He is, without any doubt, the most pragmatic person in the art sphere I have ever talked to. Most auction-house employees and gallery owners who I have met through my career have disapproved of my usage of the word “buyers” instead of “collectors”. But Mr. Altman shoots straight: “This is a shop. We sell art to a person who wants to make his life more beautiful. Do you think that in the West, all people who own a painting are collectors? In the USA, the biggest consumers of works of art are lawyers and dentists”.

Unlike most Moscow galleries – which open in art-ghettos like Vinzavod, or big exhibition centres like the Central House of Artists – Altman's gallery is located in a business and shopping centre between rows of the most expensive brand stores. “This is a perfect market for corporate presents. Imagine a vice-president of a bank who is looking for a present for a VIP client, maybe an executive of an oil company. What will he buy? We recently had a client who bought a birthday present for the director of a big company – a zodiac sign – 'Sagittarius' by Dali”, adds Mr. Altman.

Marc Chagall “Naomi and her daughters-in-law”. Courtesy of Altmans gallery

Most prints in Altman's gallery cost from $1200 to $4000 – works by Chagall and Dali – and the most expensive work in the gallery is “Flowers” by Andy Warhol, priced at $40,000. According to the website Artprice, which researches the art-market, 80% of all art-market transactions involve prices under $5000. While it is more than possible to find a good print or crayon picture by Picasso for that price (in 2011, Christie’s sold “La femme qui pleure” by Picasso for over $5 million, but the market still offers enough of his prints for a couple of thousand dollars, as well as similarly priced works by Renoir, Chagall, Miro, Dali and others), it is a true challenge to fetch a decent oil painting by a blue-chip artist given such a low budget.

Daria Razumikhina. Courtesy of Roza Azora gallery

Since this segment has become so popular among those who have not yet made their way to the Forbes list, art fairs dedicated solely to this type of art have been organized all over the world. Almost each art capital today – from Paris to New York – hosts a fair specialising in works on paper. “This is not a typical art fair in which dealers look for new names and discuss partnerships with the galleries. It is more of a closed event for real art-lovers“, says Elena Castillo, a co-owner of Roza Azora gallery, the only brick-and-mortar gallery from Russia that is participating in London's Works on Paper fair in February. We meet with Elena in her studio in an historical part of Moscow on a freezing winter afternoon. As she pours me tea in a glass in an old nickel-plated tea-glass-holder (which brings up memories of long trips by train during which tea was served in the same kinds of glasses and holders), she speaks passionately about the artists her gallery is bringing to the fair.

One of them, Ivan Yazikov, is the author of a sophisticated filigree alphabet, “a monument to letters because we type and do not write by hand anymore”, as Ms. Castillo puts it. Each of his works is an impressive, elaborate “portrait" of a letter of the Cyrillic alphabet and everything that is associated with it. For example, the one with “Я”, the last letter of the Russian alphabet, also meaning “I”, shows different languages (‘language’ in Russian starts with “я”, and sounds much like the artist’s last name): from music notes to the ones found in tattoos and playing cards.

Amanita from “Oil” series. Courtesy of Roza Azora gallery

The works of another artist that Roza Azora will be showing in London in February have less linguistic, but more cultural codes. Most of the works by the Kazakh artist Alexander Yerashov, or “Amanita", as he signs his works, are a lecture on the history of Soviet Union, as some critics' reviews called them, and “Oil” (the one commodity his native country is rich in) is no exception. The works are abundant with symbolic images, from the first Soviet man who travelled to space, to an orchestra of snowmen wearing medals from the the Second World War. Amanita, as Yerashov explained in one interview, is not a poisonous mushroom - it is just uneatable!

Even though though the middle class in Russia is becoming more interested in purchasing art, $5,000 might not yet be the right price. In 2014 some researchers estimated that Russian consumers would spend up to $3,000 on works of art. It was not specified whether this would be a work they would present to their boss, or hang in their living room, or add to their collection. Since then, the value of the national currency has dropped almost 2.5 times, making art a less affordable luxury.

“Two years ago, middle class buyers spent $30-50,000 on works of art per year. They never bought works by Ivan Aivazovsky – that was a way too expensive for them”, says Mr. Zaitsev. His gallery deals works by Western artists that go for $1,500 to $10,000. He has chosen not to change the prices, which made the works half as expensive. "Prints by the Old Masters cost from 1,000 to 5,000 eur, and there are works that cost 100,000-300,000 rubles ($1200 - $3800)”, explains Alexey Zaitsev. He tells me that at the end of 2009, his gallery sold a lot of old printed maps. “It was amazing! In November people bought only maps – mainly for presents”, he says.

Ivan Yazikov “Я”. Courtesy of Roza Azora gallery

Buying art for presents is an important driving force that keeps the gallery business afloat, I'm told by Marina Molchanova, the owner of Ellisium gallery, a pioneer of the “works on paper” segment. Unlike most other gallerists I have spoken to, she has a negative view of the situation. “I know two, three, four people who collect works on paper in Russia. People, in general, have a negative attitude towards this art. They see it as a preliminary pencil sketch for a full-size oil canvas”, she says.

“Since the beginning of the crisis, less people are interested in art from the early 20th century (which is what we deal in), and rather prefer 19th-century works or social realism [social realism – the style of art that was approved by the Communist Party in the USSR under the totalitarian regime of Joseph Stalin – ed.]”, adds Marina Molchanova.

Fernand Léger “Red Bird in the Woods”. Courtesy of Altmans gallery

As one interviewees tells me, “this is not art for the super-rich. This is for those who want to be like them”. And while owning a print by a famous modernist artist can be a safe investment and a verified sock-knocking choice, going for a small watercolour by the Prince of Wales might be a good bargain as well.