The ups and downs of the contemporary Russian art market:

from the Soviet era to the times of economic crisis

Ekaterina Drobinina

05/01/2016

“Well, this is not so expensive at all! Pas du tout!”, exclaims a good-looking, well-dressed brunette in her early 30s as she scrolls her smartphone screen which is displaying a list of prices on one of the most prominent figures of unofficial Soviet art. “Would you buy one?”, asks her friend, as they sit in on a lecture on contemporary Russian art in one of the art-schools in the center of Moscow. “One? For this price, I would buy two or three”, replies the brunette.

The perception that contemporary Russian art is currently underestimated is common. Thirty years ago, the prices for works by unofficial Soviet artists being sold at international auction exceeded the conservative expectations of everyone, from artists to officials. However, since then, the demand for these works has never managed to attain those heights again.

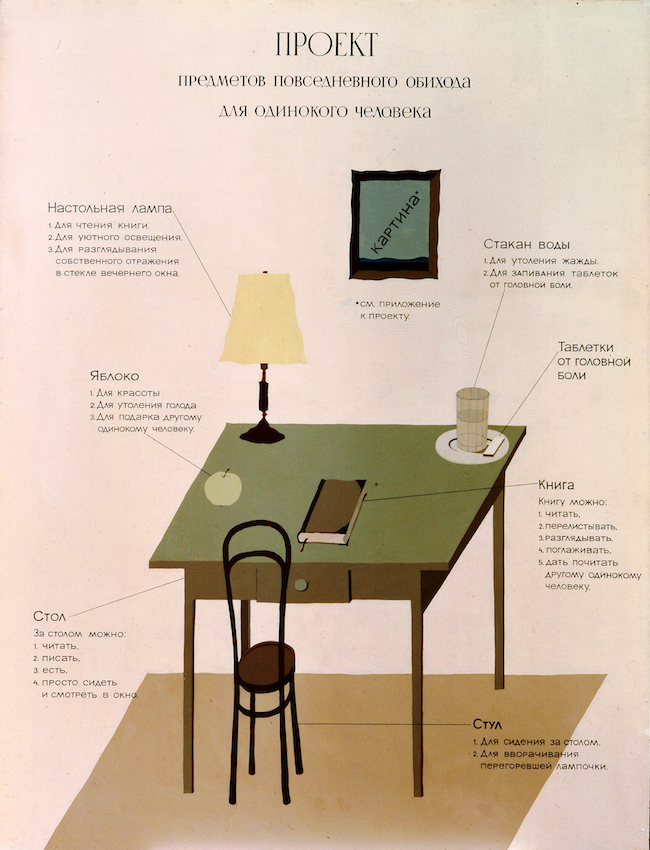

Plan for Living Space of a Lonely Man by Victor Pivovarov. Courtesy of Zimmerli Art Museum

Contemporary Russian art – or nonconformism, or unofficial Soviet art, or underground art – these are all names for the alternative art movement that came onto the Soviet art-stage (or rather its backstage) in the 1950s, and remained there until the collapse of the USSR. Surprisingly, now the works of non-conformists can be more often found in Western collections than in Russia or other former USSR countries. Even today, local collectors prefer to concentrate on either more traditional Russian artists or contemporary Western art.

A few works by nonconformists are offered by some of the auction houses during the Russian sales going on in the first week of December 2015. Despite rather pessimistic expectations ahead of the sales (due to both aggravated economic problems and political tensions), some works reached new price records. For example, during Christie’s sale, one of the highest bids among all works in general, and contemporary Russian art in particular, was “Vivaldi's Music Upon the Grand Canal” by Dmitri Plavinsky, which sold for over $212,000 – four times higher than the pre-sale upper estimate.

MacDougall’s Fine Art Auctions, which specializes in Russian art, is putting up for auction Timur Novikov’s “The USSR, the Country of the Rising Sun” (lower estimate – €28,000/$29,700). The sales catalog of the only Russian auction house that sells contemporary Russian art, Vladey, includes Semyon Faibisovich’es “Passenger” (estimated from €60,000/$63,600), and “Three Bouquets of Flowers” by Vladimir Weisberg (lower estimate: €80,000/$84,800).

The origins of Socialist Realism by Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid. Courtesy of Zimmerli Art Museum

Although there are enough works of high quality on the market, according to most experts, the demand for them is unfairly low. However, it has not always been like this.

Nonconformism appeared in the USSR when the official (and the only allowed) style of art was social realism, as proclaimed by the Communist party. These paintings usually showed the workers in the factories – their faces lit by the heat from the blast-furnaces, or soldiers fighting on the battlefields, or portraits of the top leaders of the October Revolution. Those artists whose works did not fit the criteria set by the authorities could not even buy paint or brushes, much less even have the possibility to have official exhibitions and sell their works. Most of the exhibitions took place in someone’s apartment, where artists would invite their like-minded colleagues and friends.

It was one of these “apartment exhibitions” that Norton Dodge, an American researcher, attended one day. Mr. Dodge traveled frequently to the USSR to study various economic subjects, including, for example, the place of women in the Soviet economy. A friend invited him to see the works of Lev Kropivnitskiy, one of the pioneers of the Moscow non-conformism group; with that moment, Dodge began collecting art that was not supported by the government. “He was interested in people’s abilities in a time of unfavorable and restricted conditions”, says Julia Tulovsky, the Associate curator of Russian and Soviet non-conformist art at the Zimmeli Art Museum at Rutgers University, to which Norton Dodge donated his extensive, over-20,000-piece collection in 1991. “His mission, as a collector, was to collect and preserve art that was forbidden by the authorities, and to help the artists by reassuring them that their art had value on a larger international scale,” she adds.

In 1977 Dodge organized the exhibition “New Art From the USSR” in Washington DC, close to the location of the Soviet embassy. It was not the first time that Western society saw abstractions by Lidia Masterkova, dark still-life pictures by Oskar Rabin, or magnificently colorful paintings by Oleg Tselkov. Although some of the artists were very unpopular at home (the notorious open-air exhibition of 1974, held in the southern part of Moscow, was broken up by a bulldozer), European and American galleries and museums had already been showing their works.

By the 1980s, many foreigners who visited Moscow would buy the work of almost anybody who belonged to the nonconformist movement. However, many of the works were purchased as souvenirs, say some art experts. And according to one Russian gallery owner, now they are likely forgotten, sitting in garages and covered with dust.

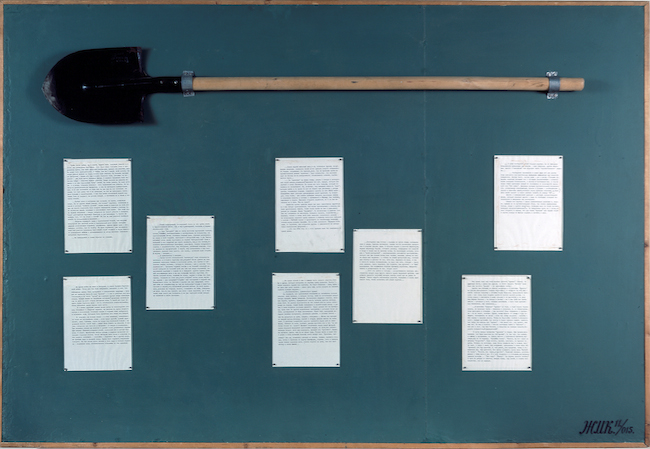

Shovel by Ilya Kabakov. Courtesy of Zimmerli Art Museum

A souvenir from the Soviets – even though a pricey one – was something many foreigners went for when, in 1988, Sotheby’s organized the first auction of Russian avant-garde and nonconformist works at the International Trade Centre in Moscow. The Soviet government claimed that they wanted to establish prices for this art on the international market, and hoped the auction would bring in up to $900,000. However, six works by Grisha Bruskin alone, including his “Fundamental Lexicon” (a paneled work showing figures that together represent the collection of Soviet values or ideals: the Olympic athlete, the revolutionary, the scientist, the Pioneer, etc.), which was the most expensive work by a nonconformist artist to be sold that evening, fetched $865,000. The sale turned out to be a spectacular event and brought in a total of $3.4 million, a result that hardly anyone could have anticipated.

Many artists who were present at the sale said that the Sotheby’s auction shattered the existing hierarchy. The works by more established artists did not reach the record levels set by the less-known artists, i.e., those “who had been at the periphery of things for years”, as Andrew Solomon puts in his book,“The Irony Tower: Soviet Artists in a Time of Glasnost”. It was clear that the previous hierarchy had nothing to do with the quality of the works or the talent of the artists, but rather with a cultural code that was encrypted in the works of art, one which could not be seen and understood by the Western audience.

Today, collections of Soviet artists can be found in various parts of the world. Julia Tulovsky of the Zimmerli Art Museum admits that her museum is sometimes approached by people who own works of unofficial art. In 2005 they received a donation of 200 works from the San-Francisco-based collectors Nina and Claude Gruen, who became interested in this art after seeing a painting by Oleg Tselkov in a gallery window in the1980s. Unlike Norton Dodge, they had never visited the USSR before.

But according to Natalia Kolodzei, the executive director of the Kolodzei Art Foundation in New Jersey, the market for these works of art has never ceased to exist. The Kolodzei collection, started almost half a century ago, includes works by over 300 artists from Russia and the former USSR. However, attracting buyers outside of Russia won’t happen if they're not educated about the genre with events like exhibitions and accessible books on the subject, she adds. (The Foundation’s current exhibition, “Leads to Fire: Russian Art from Non-Conformism to Global Capitalism”, includes works from the earliest years of nonconformism to more recent works).

“The art market does respond to the challenges in a market economy – by reflecting changes in culture while also reacting to the variable nature of contemporary art,” says Natalia Kolodzei. “The contemporary art market has a narrow niche compared to traditional art. However, taking into consideration problems with the limited number of quality works of traditional art or Russian Avant-garde art, plus provenance problems, contemporary art could play a role in the Russian art market”.

While political and social implications of nonconformism were the main features that used to attract many Western collectors, these features have turned out to be unappealing to today's collectors from Russia and the CIS. As the practice of other countries (for example, China) shows, the demand for contemporary national art must be stimulated by local collectors. However, Russian customers prefer to focus more on the early 20thcentury, says Jo Vickery, Senior Director and Head of Sotheby’s Russian Department. “[This] is not surprising since Russia reached its cultural apotheosis at this time.”

Danger by Eric Bulatov. Courtesy of Zimmerli Art Museum

The only period when contemporary Russian art was selling well was before the 2008 crisis, which is when, boosted by the wealth of nouveau-riche collectors, Russia’s art-market reached its peak. In 2007 and 2008, Sotheby’s organized two auctions dedicated to contemporary Russian art. They both resulted in record prices for the works of nonconformists, some of which, for example, Ivan Chuikov, were underestimated by the Western community during the Sotheby’s sale 20 years earlier. The resulting selling prices for the works by Evgeny Chubarov (£288,800/$568,000 for “Untitled”), Erik Bulatov (£198,000/$390,000 for “Revolution-Perestroika”), Oleg Vassiliev (£468,500/$927,000 for “Before the Sunset”) and Semyon Faibisovich (£264,000/$523,300 for “Beauty”) ended up being several times higher than their pre-sale estimates.

Although experts praised the interest that Russian collectors were finally showing for contemporary art from their own country, it did not last long. “Although we continue to see good prices achieved at auction for Russian contemporary artists, this market, as a whole, is still relatively underdeveloped,” says Jo Vickery. “Some contemporary Russian artists grew extremely quickly in value before the crisis, but have not managed to reach their pre-crisis levels since then,” she adds.

In October 2015, MacDougall’s organized its first Soviet and Post-Soviet art auction, thus proving that demand for the works of nonconformists continues to exist. Among the works on sale by unofficial Soviet artists, the top price of €63,141/$71,878 was achieved by Vladimir Weisberg’s “Reclining Nude” (although, strictly speaking, Weisberg stands apart from both nonconformists and official Soviet artists) – a translucent image of a lying figure, viewed as through a smoky haze.

Since the success of the Sotheby’s sales in 2007 and 2008, the only occurrence of a work by a nonconformist artists passing the one-million-dollar benchmark was at the BRIC sale in 2010: organized by Phillips in London, one of the famous “Entrance-No Entrance” pieces by Erik Bulatov sold for £713,250 ($1,085,600). This can be seen as an exception to the falling trend of buying Russian contemporary art in times of economic turbulence. However, at the same time, it proves that when a good work of art comes to market, collectors will bid high for it despite any economic challenges.